By Keri O’Shea

What is it that defines the term ‘gentleman’? Without a doubt, it is a term which remains nebulous, and one which has changed throughout its history; you could also make the case that the term itself has lost much of its meaning in the modern day, but perhaps we can still say some things about it with a degree of certainty. Gentlemanly behaviour, I would argue, connotes decency, dignity and deference. A gentleman may have humble origins (the term seems to have lost much of its association with ancestry) but a noble character and actions; a gentleman would almost certainly behave according to a profound sense of propriety, and it is sad that the notion of a man acting according to this sense of propriety is seen by some as archaic, because surely it is anything but. However, whatever one’s social mores might dictate, there is something else I feel I need to add to the definition. The concept of the gent is, in so many ways, an ineffably English phenomenon. Oh, sure, you may find gentlemen in many traditions, cultures and places, but somehow, it seems most intricately bound up with ideas of Englishness – which is yet another concept which some people find easy to castigate in these cautious times.

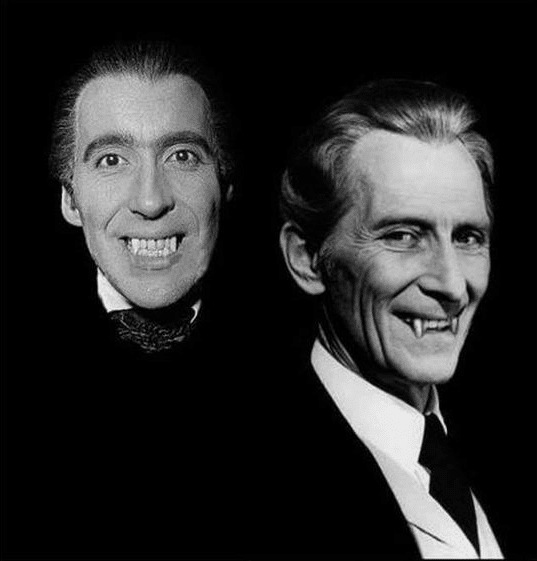

In The Image of the English Gentleman in the Twentieth Century, author Christine Berberich quotes Sir Sidney Waterloo (himself an English gentleman) and his definition of the gent as ‘he who feels himself at ease in the presence of everyone and everything, and who makes everyone and everything feel at ease in his presence’; when I read this definition, I was struck by how much this reminded me of the great Peter Cushing, the man who is for me, the quintessential English gentleman. Cushing is a man about whom I have never heard or read a bad word. Anyone, anywhere who worked with him speaks fondly of him, of his manner and his conduct; and, immediately when I think of Cushing, I think of his dearest friend Christopher Lee, with whom he made a staggering twenty-two films over a period of thirty-five years. If Cushing was the quintessential English gent, then his friendship with Lee would seem to be the quintessential friendship between gentlemen; Cushing the more pacific character to Lee’s breviloquence, but together, a brilliantly-matched, deeply-attached amity.

And it was horror which initially forged this friendship – Hammer Horror, to be precise. Peter Cushing had initially eschewed a career as a surveyor – a dependable, respectable but ultimately unsatisfying job – and had become an actor instead. At this, he enjoyed modest, steadily-building success, appearing in theatre (including Broadway) before at last moving into cinema. Cushing and Lee appeared in the same film together as early as 1948, when they each took a role in Sir Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet, and again in a version of Moulin Rouge in 1952, but they still had not yet met. This was to change in 1957, when each was cast in Hammer’s first full-colour horror film, The Curse of Frankenstein, a film which was successful enough to open the floodgates of Kensington gore and establish a strong horror presence for the Hammer studio which would last well into the 1970s. Christopher Lee, however, was not overly pleased with his first impressions of the film he was about to shoot. Lee’s ambivalence (and sometimes downright dissatisfaction) with Hammer’s modus operandi would continue for as long as he worked with them, but nonetheless, the studio united him for the first time with the actor who would become his ‘dear fellow’.

In his autobiography, Christopher Lee recounts their first meeting, which took place on the set of The Curse of Frankenstein. “Our very first encounter began with me storming into his dressing-room and announcing in petulant tones, ‘I haven’t got any lines!’ He looked up, his mouth twitched, and he said drily, ‘You’re lucky. I’ve read the script.’ It was a typical wry comment. I soon found Peter was the great perfectionist, who learned not only his own lines but everybody else’s as well, but withal had a gentle humour which made it quite impossible for anybody to be pompous in his company.” Their friendship was born. It is ironic that, as their friendship grew, they tended to play on-screen adversaries, most notably of all Van Helsing and Dracula; the end sequence of Horror of Dracula (1958) is for me the ultimate Dracula scene committed to celluloid. Cushing himself reflected upon his role as Van Helsing: “To me, Van Helsing is the essence of good pitted against the essence of evil…I believe that the Dracula films have the same appeal as the old morality plays, with the struggle of good over evil, and good always triumphing in the end.” As Van Helsing looks peaceably through the day-lit, stained-glass windows after dispatching Dracula in what must have been a very physically tough scene to play, you can see what Cushing means when he said, “I suppose in a way it is possible that I was pre-ordained to play Van Helsing. For although I am not a religious man, I do try to live by Christian ethics and I believe in the truth as set forth in the New Testament. I can see so many of the elements of good and evil in life, and this seemed to give me added strength in my screen battles with the powers of darkness.”

However, the loss of Cushing’s beloved wife Helen in 1971 was to cast a pall of sadness over the remnant twenty years of his life; although he continued to work and always performed to the best of his abilities, his heart was never again in his work in the same way, and his friends, Lee included, understood this. It is a matter of great sadness though that what is probably his best-known mainstream role – in Star Wars – was to occur in those years after his greatest enjoyment in his career had passed. Lee was also to work his way into the mainstream, and now in his ninety-first year continues to work at a frenetic pace. Both men always remained in contact; on occasions they celebrated their consecutive birthdays on the 26th and 27th May together, whilst they often exchanged letters and gifts in the interim, with Lee commenting on the “entertaining letters and satirical verses” which he received from him. Yet however much he took pleasure in his friendships, Cushing was always honest about his state of mind following Helen’s demise. “She was my whole life and without her there is no meaning. I am simply killing time, so to speak, until that wonderful day when we are together again.”

And so he waited, and he worked, to fill the time. As another irony of both Cushing’s and Lee’s respective careers, neither of them were fans of the horror genre. Cushing, whilst always characteristically charmed and humbled by the letters he received regarding his horror roles was far more glad of the opportunities which genre film afforded him than he ever was a fan of the end product. In a 1985 interview, he said, “It gives me the most wonderful feeling. These dear people love me so much and want to see me. The astonishing thing is that when I made the “Frankenstein” and “Dracula” movies almost 30 years ago the young audiences who see me now weren’t even born yet. A new generation has grown up with my films. And the original audiences are still able to see me in new pictures. So, as long as these films are made I will have a life in this business – for which I’m eternally grateful.”

As the friends’ careers diverged somewhat, Cushing was to continue working as he battled prostate cancer; it was the illness which was eventually to end his life in 1994 when he was eighty-one years old, after a ten-year battle. Christopher Lee recounts of their last meeting in that year, “There was something a little bit different about Peter, waiting for the end: for twenty-three years since his beloved wife Helen died, his friends realised that he wouldn’t mind packing up on this earth to join her. Vincent [Price] once, in a phone call to me, asked, ‘Is he still expecting Helen to be there to greet him?’ And I said, ‘Looking forward to it.’ And Vincent said, ‘And what if she’s out?’ I said, ‘I shall tell him you said that, Vincent,’ and when I did, Peter laughed fit to dispatch him immediately on his journey. When he’d recovered he said, ‘Only Vincent could say such a thing, and only you could pass it on.'”

Peter Cushing was and is one of the most well-loved and well-known actors of his own generation and of those which have followed. It is also difficult to visualise Cushing – at least for me – without also visualising Christopher Lee. Perhaps the friendship between these two men – and its loss – speaks to us so keenly because it speaks to us of something else above and beyond itself. To return to Christine Berberich, whose book on the phenomenon of the gentleman we looked at at the start of this article, she suggests that the notion of the gentleman is at least partly bound up in the idea of nostalgia, of a past we miss. By looking to men like Cushing, we are looking to the past; in his loss, we see the end of a way of life, we see the demise of a certain value system, or a manner, or simply a way of doing things. But then, of course, we are also affected by the loss of Cushing as an individual, someone whom we did not know personally, but whose evident value system, and manner, and way of doing things we respected enough to mourn. This is not to denigrate the loss of those who did know him personally, however, and it is only fitting that his greatest friend have the final word in this regard. Lee – a man known for his honour and gravitas, but perhaps less for his emotionality, nonetheless had this to say. “At some point of your lives, every one of you will notice that you have in your life one person, one friend whom you love and care for very much. That person is so close to you that you are able to share some things only with him. For example, you can call that friend, and from the very first maniacal laugh or some other joke you will know who is at the other end of that line. We used to do that with him so often. And then when that person is gone, there will be nothing like that in your life ever again”.

But perhaps I might be permitted to add one note of positivity: as much as we mourn the loss of a great actor and a man who does not seem to have an equivalent in these times, we are also celebrating the centenary of Cushing’s birth. We can say that those of us who continue to adore seeing Peter Cushing – and of course Christopher Lee – on our screens have imbued them and their friendship with a particular kind of eternal life, as their warmth, honesty and integrity continue as a pleasure to observe.

Select Bibilography:

Berberich, Christine (2007) The Image of the English Gentleman in Twentieth-Century Literature: Englishness and Nostalgia (Ashgate Books).

Haining, Peter (1987) The Dracula Scrapbook (Chancellor Press).

Lee, Christopher (1977 [1998 edn.]) Tall, Dark and Gruesome (Vista Books).