We’re busy, busy, busy as we get underway with Indonesian horror movie The Hole (2026), aka The Hole, 309 Days to the Bloodiest Tragedy (which rolls less well off the tongue). Leading with a notice which we normally see on the end credits of a film – ‘Any similarity to actual characters, places or events is coincidental’ – the film follows this up with what feels for all the world like a realistic framing device, because it is: ‘On September 30th 1965, seven high ranking army officials were murdered’, an event which, we’re also told, was considered a national tragedy, and forms the basis for a version of events we’ll see unfold.

In most films, we have the realistic introduction and the reminder that the film is fictional separated by around ninety minutes or so: here, as well as being inverted, it feels rather fitting that the lines are somewhat blurred, as The Hole does struggle to settle into one mode of storytelling, only finally deciding the issue towards its close.

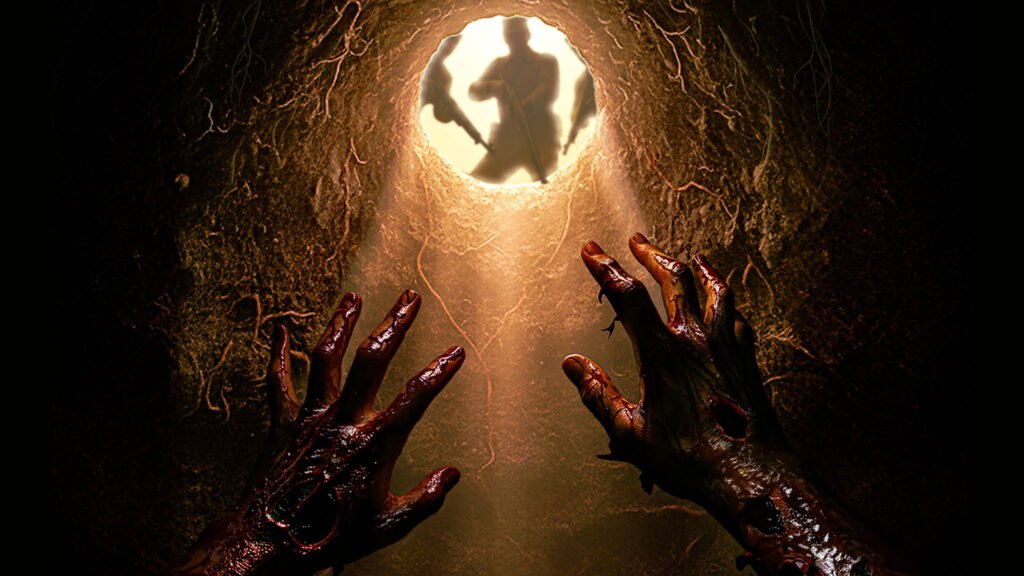

Continuing straight on from the opening credits, we see a woman’s body being deposited into a (or who knows, possibly the titular?) hole in the ground in an Indonesian village – a village where two guards, one pausing to pretend to read from a torn page from a grimoire, are disturbed by women’s screams: one from a longhaired ghost in the woods (oh come on, it’s clear) and one from the wife of the chief of police, when she finds his murdered body. Which has a big hole in it. Ah. The guards flee in each direction to attend to each situation; we don’t see the immediate aftermath, however, as we switch to a more functional situation, the wedding of army officer Sugeng and new bride Arum back in Jakarta: they’re adopted siblings, but no matter, as with very little time to celebrate anyway, Sugeng has to head off to investigate events in the rural village of Lobang Boaya – site of the gruesome events we have already witnessed, and a few more besides.

As Arum commences her marital duties by tending to her by-now very frail father and father-in-law, finally convincing him to move to Jakarta where they can care for him, Sugeng is soon faced with the harsh realities of a spiralling murder case: bodies are turning up carved with rather negative words which – the army fears – given the influential figures who have been bumped off, could point to some sort of incoming political coup (hence why it’s Sugeng doing the investigating, rather than the police). His investigation seems to be a fairly conventional whodunnit, at least at first; Arum, meanwhile, is being hit with a slew of supernatural phenomena, from which derives the film’s most successful supernatural scenes. It’s made fairly clear to the audience that the supernatural phenomena are real, although the film prevaricates to an extent on whether this film is going to be more of a political or a supernatural horror – as in, which elements will come to dominate the screentime.

In establishing its characters and themes, The Hole also leans very heavily on on-screen text to tell us who everyone is – names, job roles, and other relevant context; together with the shifts in timeline and location, this can make the film feel rather hectic, as well as – whisper it – confusing, particularly in the first thirty minutes. But it’s at great pains to paint a picture of a community tarnished by corruption and nefarious practices, something it does successfully do, picking up on the spectres of mid-20th Century political upheaval in Indonesia: Communism, Islam, the status quo – these all spend time in our eyeline, each contributing something to the fomenting tension (in, by the by, a pretty plausible 1960s setting).

So it has a real set of social and cultural anxieties at its core – but, given its supernatural content, is The Hole a scary film? Its director, Hanung Bramantyo, has enjoyed a very successful career in his native Indonesia to date, with his film Miracle in Cell No. 7 (2022) the seventh highest grossing title of all time there. But that’s a comedy, and as much as he has turned his hand to several different genres, it’s fair to say horror isn’t his most frequent output, nor his first love. Perhaps as a result of this, The Hole struggles from the outset. Clearly an attempt to marry the supernatural horrors of what’s now broadly classified as J-Horror (which didn’t seem to either really derive from, nor infiltrate Indonesia much at the time) with more down-to-earth fare – essentially, the evil that men do – it’s ambitious, for sure, but with a more streamlined plot and more time for concerted, abundant horror content, it could have all landed more successfully.

As much as a black magic storyline seems to be absolutely de rigeur for today’s Indonesian horror audiences, it never quite takes off in The Hole, at least – and this is important – for this European reviewer. It feels like a dash to get everything across the finish line, too, although to give it its dues, The Hole does manage to tiptoe a few horrifying ideas past the film censors along the way, even if this is more implied and CGIed than overt. However, for all that, it’ll almost certainly find its audience, given the reputation of the director and his attempts here to splice criticism of Indonesian (rather than, say, Dutch or Japanese) power with something paranormal and inexplicable, all centred on a rural village which comes to serve as a microcosm for a range of social ills.

The Hole (2026) receives its world premiere at the International Film Festival Rotterdam on February 3rd 2026.