Super Happy Fun Clown (2024) opens with a woman – dressed as a clown – who has a hostage, engaged in a confrontation with the police. So, if nothing else, the title can be taken literally; there are no (or not only) metaphorical clowns here. Adapted from a short film of the same title (and with the same cast) made just a year earlier, the feature struggles in some respects with issues which often beset films expanded from a few minutes to ninety or so (and funnily enough, I remember saying similar things about a clown-themed short film-to-feature a decade ago). However, despite these issues, there is an interesting thread here which it shares with a number of recent indies, all equally concerned with the perils of modern ideas of fame, success and ‘being somebody’.

Having started with the shoot-out, the film next skips back twenty years to 2004: so it’s a loop, and we’ll be back to the shoot-out in due course. This is Jen – the clown-loving woman – as a ten year old child. Jen is precocious, but she has a hard-nosed mother, a mean big sister and jealous classmates: as a result she prefers to keep herself to herself – but she loves clowns, whether watching them, collecting clown-based artwork or drawing terrifying versions of them. This expands into Jen’s adulthood, tracking more and more with a much-needed escapism from the ubiquitous dreadful husband and dire day job. Jen is a clown in her spare time, but to be fair hers is a dreadful business model: roadside clowning in a sparsely-populated area is never going to make ends meet.

Despite a few, odd moments of levity, Jen knows she’s blown it. She could have gone places, which in modern society (with her mom as a mouthpiece) means a white collar job, selected from a certain list. Jen is, to some extent, signed up to this too: she mumbles the excuse for her cartoonishly deadbeat husband that ‘he was a lawyer’ when they first met (before he was laid off for soliciting a minor). Still, Jen is aware that it’s time for a change. If she is to ‘be somebody’, then life as she knows it must come to an end. Sadly, this doesn’t mean manageable, expected changes, like a career change or a divorce…

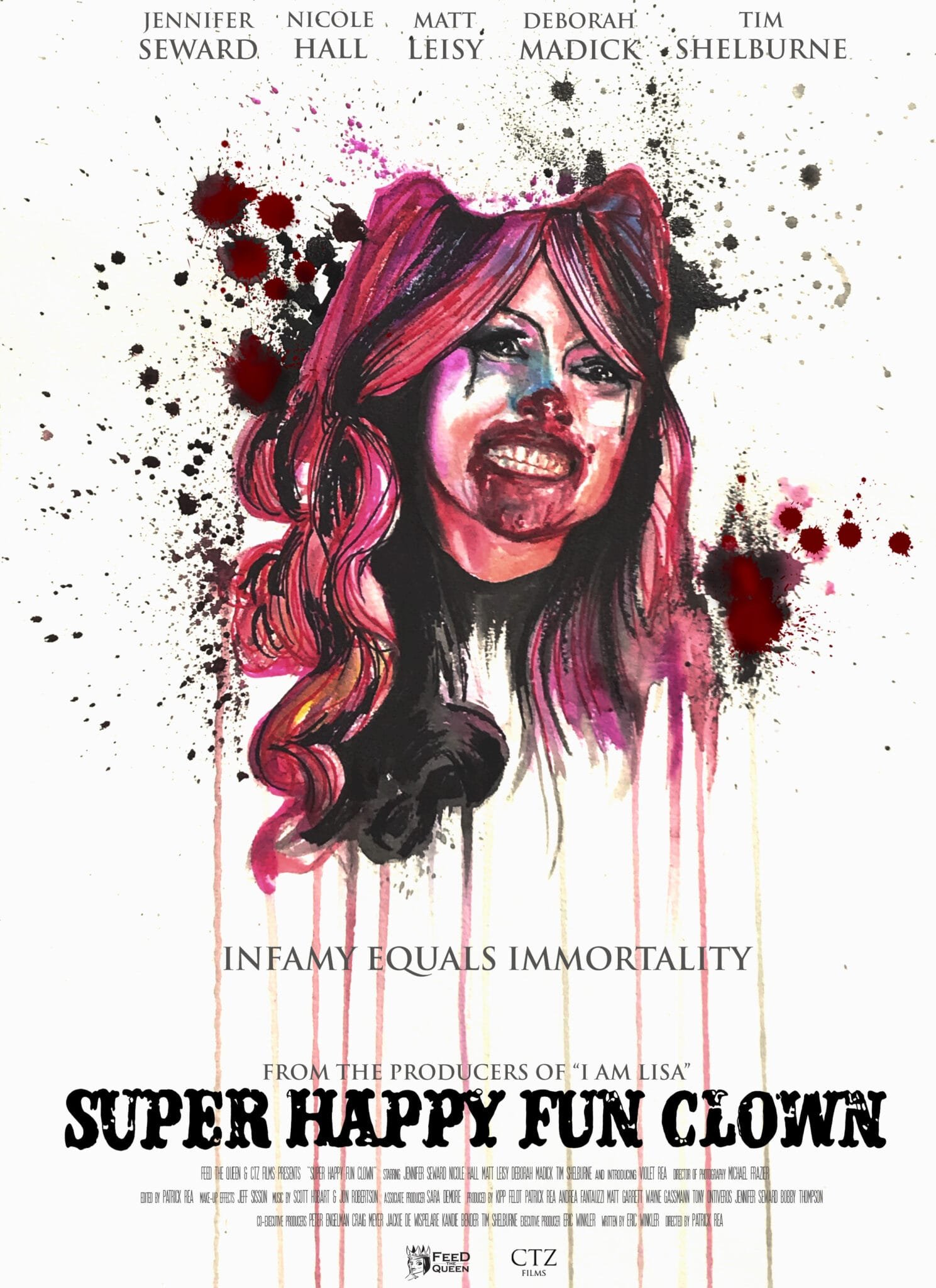

It’s not quite made explicit and nor, really, is Jen’s sudden obsession with notoriety-as-fame made clear; aside from some hints at her love of horror cinema and serial killers, she seems almost entirely divorced from media consumption, whether social or otherwise, and doesn’t seem to have surrounded herself with the kinds of people who are in the loop either. Nonetheless, when she comes to take stock, it seems that notoriety is the kind of success she now craves. We’ve certainly seen enough to clock the death of her optimism, as well as the fact that only whilst dressed up as a clown can she ‘perform’ joy, though that doesn’t last, either. Given the importance of clowning to Jen’s progression in the narrative, lots of the key plot points are painted in broad strokes to match the imagery and ethos of clowning itself – pratfalls, primary colours, gurning and exaggeration.

However, as the film moves on, it can be tonally quite hard to place. The exaggerated artifice of ‘Jenn-O’ can be comic or tragic; the shift from brittle but bright child to flailing adult relies heavily on the trope of the bad mother for its pivot, but oddly, doesn’t fill in the backstory of the obsession with the clown – as much as we can glean that greasepaint serves as a suitable disguise for an unhappy kid, and as a habit for an unhappy adult. So it’s an unhappy clown – a tragic figure – rather than a pure psychopath which we follow into the middle act of the film; Terrifier, this ain’t. But then again, the film soon ramps up the horror content, both by paying horror lip service in its script and by showcasing an increasing number of homages and murder set pieces as Jen finally unravels. The Halloween setting is a key horror trope, too.

Is it meant to be funny in places? It certainly seems that way: little visual touches (like the Richard Ramirez wall calendar) invite us to laugh; the Three Stooges blare out of the TV set in Jen’s house; the gore is OTT enough to void empathy with the victims. By the by, if director Patrick Rea and writer Eric Winkler want to continue to embed cover versions of Type O Negative into their films, then I am here for it. But then, the film feels more philosophical in places, which is fitting, given this was the focus of Jen’s (‘useless’) degree. However, when push comes to shove, it’s ‘bad fame’ Jen opts for, which eventually brings up back to where we started – a shoot-out, and a kind of reckoning.

At its best, and despite some tonal issues, Super Happy Fun Clown is another independent film which examines the disconnect between personal fulfilment and a version of ‘fifteen minutes of fame’ which is both so possible and so out of reach in today’s cultural climate. Working hard to enact the shift from person to persona, Jennifer Seward turns in a good performance here, and certainly the pressures of ‘making it’ from the perspective of indie filmmakers in a tough business adds an additional layer of interest to this project.