Made in 1972 for Spanish TV, Antonio Mercero’s short film La Cabina (The Phone Booth) didn’t appear on British television for around a decade after that, but it was a case of once seen, never forgotten for those people who first saw it in the early Eighties, appearing as part of a suite of programmes on the-then new terrestrial arts channel, Channel 4. Now, in a post-analogue world which has, funnily enough, more or less dispensed with phone booths, it can be seen via YouTube – and it definitely should be seen.

Before reading the article, do yourselves a favour and check it out now, if you haven’t already done so. The article may contain spoilers.

First impressions reveal an oddity of a film which now functions as an interesting time capsule but, like so many other hitherto lost oddities, it’s so much more than that. It’s not just about the brief snapshot of 1970s Spain which it offers, or its now archaic technology. It leads the audience from one faintly silly, slapstick-adjacent situation into a barely understood, but frightening alternate reality where, just behind the scenes, strange forces are at work, able to act with impunity as life rolls merrily on around them. There is great cruelty here, rising to a dismal crescendo which suggests far, far more is at play. La Cabina is a masterclass in what can be achieved with the short film format -actually, thirty-five minutes here – given that, still, hundreds of brilliant short films are deprived a wider audience due to so little space being made for these films, in either television or cinema programming.

The film starts simply enough, capturing a brief and unremarkable moment in the everyday reality of the 70s: as the world is waking up, some men arrive with a flatbed truck to install a flashy new phone booth in a town square. Once done, they depart, and we meet a father and a young son: the father, a nameless businessman (and this is important) sees his son onto the school bus before hopping into the phone booth to make a quick call.

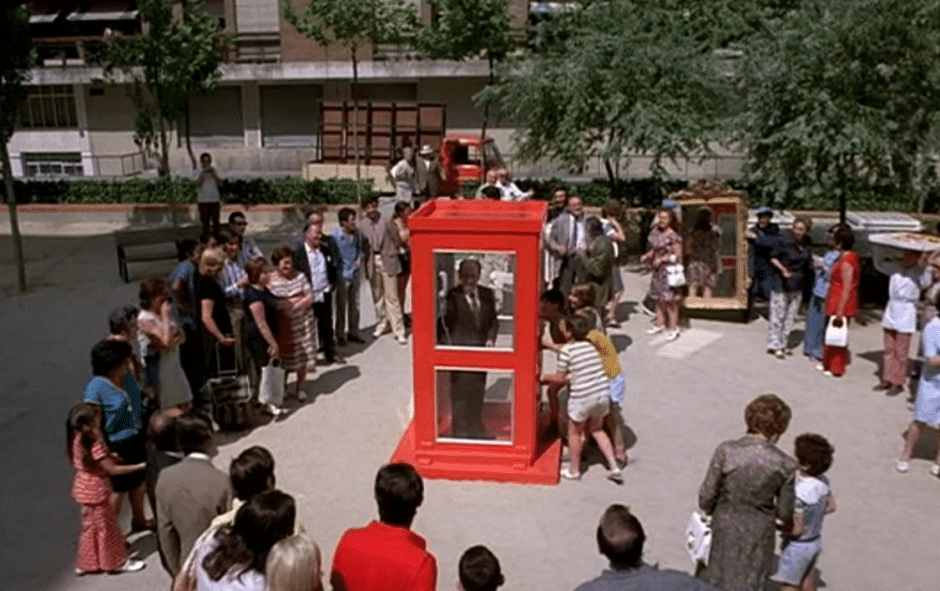

Flashy and new it may be, but the phone isn’t actually working. By the time the man (José Luis López Vázquez) realises this, the door has gently closed shut behind him – and it’s stuck. He tries and tries to get the door back open, but to no avail. As passers-by begin to take notice of his frankly daft predicament, they start trying to help: their efforts attract more people, and before too long there’s a minor stir in the town square, with people gathering to observe what’s going on. Attracted to the hustle and bustle, lottery ticket sellers and people carrying snacks arrive. An old lady is helped to prime position and given a chair. Meanwhile, inside the booth, the man cycles through a range of emotions, from annoyance to embarrassment, even displaying some awareness that yes, this is all a little ridiculous.

Finally, the police and fire service arrive: there’s a sense, when first watching the film, that this will be the clincher – the powers-that-be will be able to do something because that’s what they do, and it’s intriguing to be walked through that expectation at this point and then walked straight out the other side, because things don’t come to pass that way. Things take an unexpected turn when the same company – is it a company? – arrives and puts the booth on the back of the flatbed, trapped man and all. They look like they know what they’re doing. That’s more than the police or fire service did. The crowd cheers, then goes back to whatever it was that they were doing before the morning’s entertainment; Mercero has created an H G Wells-worthy crowd scene here, guilty of bystander apathy at best, or boorish, clueless and mean at worst. The film also plays with society’s tendency to just trust that ‘things will get sorted out’ somehow. The people who arrive in overalls with a suitable vehicle must surely be legitimate and organised, and perhaps they are, in a sense. But what looks like help, isn’t help at all; it’s a continuation of a pre-planned ordeal. Meanwhile, the man – who is completely ignored by the drivers, like a piece of cargo – gets transported out of the city, through an otherwise timeless and picturesque rural Spain. Beautiful, sure, but remote, unfamiliar and certainly not somewhere you’d associate with a quick fix or a specialist team of mechanics there to deal with this inconvenience. More to the point: they’re not stopping. The journey goes on.

Steadily, hopes for an expected resolution are being removed. You can feel the film’s firm foundations being eroded. Mercero does this oh-so artfully, but one moment, relatively early in the film’s runtime, is key, suggesting very briefly that elsewhere, this same farce has been taking place. Our protagonist glimpses another man, a man just like him, a businessman in a suit, also being transported somewhere. They are briefly able to lock eyes: the other man is already more downtrodden, but our protagonist is not far behind him, and this sequence is more intriguing for the way it raises new possibilities. So, is this a farce at all, then? It’s starting to seem otherwise. What is actually going on remains to be seen…

And, arguably, is never revealed. The rising horror of the film’s end sequences are so memorable because we are made to acknowledge a strange, organised process, the upshot of which remains ultimately mysterious to us. What we can say is that someone, somewhere clearly has a lot invested in what now appears to be a process of trapping and transporting lone men to a vast, remote plant of some kind. The clearest aspect of this horror is revealed in reverse: we see a number of empty booths, lined up and being cleansed by other workers. Then, where our journey finally comes to a stop, we see a large number of booths which are still occupied – by other businessmen, or rather: dead or dying businessmen.

These deaths serve no clear purpose. This isn’t Soylent Green (1973) – we don’t see anything like that process taking place, and this isn’t Phantasm (1979) either – there’s no supernaturalism or science fiction being suggested here. So why has this happened? Why have these men been killed by neglect; why are the booths being cleaned and reused, presumably to secure more people to kill in the same way? What is this all for?

From the moment we glimpse the second man who is being transported at the same time as our protagonist, we can glean that there may be something significant in two almost identical men being taken in this way. By the time the film ends, we can be confident, at least, that this is a factor. Apparel, age, sex and class: the men are more or less identikit. Much has been made of this, right down to interpreting the film as a coded critique of the last days of Franco’s Spain, but perhaps victimising a typically powerful and prestige group in this way – businessmen are more often villains than victims in the horror genre – is a reminder that everyone can be vulnerable, even the comparatively powerful.

It’s also possible to say that the man’s plight is seen as humorous by the watching crowd in ways which would not be the case if a little girl or a young woman with children were trapped in that booth. In fact, at first the businessman’s ordeal becomes a kind of alpha male contest, where passing males start to get competitive about who’s going to free this poor, helpless desk-job sap sweating uselessly in the phone booth, clearly unable to free himself. Is the film suggesting that these kinds of men are expendable? Replaceable? It certainly does suggest that, if so many of these men are disappearing, that society is continuing to function without them, but by focusing on one individual, La Cabina does not just become a simple or generalised commentary on the fate of the missing, or even a treatise about sex or class.

The man’s last clear remembrance of his now former life is a memory of his son, whom he loves: a child that he passes on the road, innocent to what is going on, waves to him as he passes. Perhaps it’s then that our businessman realises nothing about this situation is likely to be rectified in normal ways, and he seems to be genuinely sad and fearful here, not simply annoyed as previously. In some respects, the man is going through the stages of grief, grieving for himself and his loved ones. In many respects, the absence of dialogue enables this progression and enables us to follow it: it’s implied that the booths are soundproof, so the man’s only communication for the most part of the film is non-verbal. When it finally dawns on him that he will never escape, then the stages are complete, and he has also become an Everyman, suffering silently to the end.

Throughout this wordless journey, Mercero adds powerful visual symbols which underline and underpin the development of the narrative. From the knitting women reminiscent of les Tricoteuses, the women who calmly knitted as guillotined heads hit the baskets during the French Revolution, to the glass-sided coffin which mirrors the booth as it passes, death imagery dominates the film, though again, sometimes these pieces fall into place after the fact, as you find yourself emulating the businessman by casting your eye back over events so far, looking for clues, anything to justify what’s going on. There is also a strange parity drawn between the tragicomic elements in the film and the inclusion of circus performers at the film’s midpoint, with a group pausing their practice to observe the vehicle and the man as they pass. Finally, the film features an unconventional noose in the form of a strangulating phone cable; a man in a nearby booth, with his own untold story, has opted to end his own life. It’s one of the last things which our protagonist sees, and one last way in which Mercero equates the world of the booth, with its harried users, business calls and urgent matters to attend, with something horrifying and inescapable: it’s a particularly vicious, then-modern and everyday update on a timeless symbol. And this would be a particularly hideous place to end the film, but there’s more.

The film turns out to be cyclical, which in itself contributes to the eddying, unspoken darkness which dominates by the end credits. As things draw to a close, we see the process repeat: a pair of the equally faceless, unknown men are back, installing another phone booth in the square. Devoid of any real understanding, left adrift without answers, all we see clearly is that life apparently continues in everyday, modern urban Spain, where individuals can apparently be quickly forgotten and where equally faceless organisations veer between feckless and malign. They can be taken for granted and overlooked by the easily distracted masses; in the case of the people who remove the phone booth, this is what enables them.

Centred throughout – as if we’re likely to forget – is a simple phone booth: today the phone booth is a bit of an anachronism, true, but at the time it was an everyday, even humdrum facility, and part of normal life. To repurpose something so ordinary and overlooked (only the man’s son bothers to remark that the phone booth looks ‘new’) to make it one facet of an inscrutable, mysterious and harmful agency is the prime destabilising act of the film, however extreme and mysterious the outcome remains. We might like to wonder about equivalents today, or debate whether our increasingly connected and surveilled society has different, newer horrors of its own. But in any case, La Cabina, with its simple premise and execution, feels very timeless. It’s ultimately a sad, inexplicable story which allows us to witness our protagonist’s plight but not to make any further sense of it, although it tantalises that someone – someone powerful – could explain. The film has just enough of the strange, and just enough of the familiar, to ensure it still packs a genuine punch.