A wounded hand disappears into nothingness as a modern, chain link fence divides us, at least initially, from an idyllic English churchyard; if Penda’s Fen (1973) can be seen as fairly recusant in its treatment of themes and narrative structure, then you could equally argue that it spells out its key themes, or at least visual themes, in its opening seconds. Harm, even self-harm, injury and separation, against the backdrop of a church – now part of the beauty of the English landscape, once a new imposition – but regardless, for a thousand years, a conduit for meaning, for learning and self-knowledge. Perhaps to see and to feel kinship with England, you must both reconsider these old certainties, and see past them, to the timeless beauty and wonder which has so long housed these houses of God. This is certainly one of the ideas explored in Penda’s Fen: England, and Englishness, are a rich and vital seam running through everything here. The development of this idea throughout the film is generous, expansive and subtle, and always complex and beautiful. Nonetheless, and for all the film’s mysteries, we are shown something of what is to unfold at the opening credits: Penda’s Fen is a reckoning of selfhood, of identity, as a young man navigates through a formative period in his life which is, at the beginning of the film, disintegrating before him.

“I am mud and flame!” Stephen Franklin, child of England

Stephen Franklin, the rector’s son – and inhabitant of the rural rectory we also see in the opening seconds of the film – is seventeen, and on the brink of adulthood. His life has been carefully coded and marked out for him by an array of old, reliable, but strangulating certainties: school, exams, a military scholarship; at home, he has the comforting, rote principles of Christian belief, to which he holds fast, having been raised in a religious household, his father a prolific thinker and speaker on faith. But the Stephen we meet at the beginning of Penda’s Fen is in crisis, and this makes him sharp, churlish. He is poring over an essay he has written on Elgar’s song, The Dream of Gerontius – as he listens to the same piece of music – but his fascination with the soul of Gerontius as it arrives not into Heaven, but Purgatory, seems to trigger a range of mixed feelings in Stephen, primarily a yearning for a religious experience of his own. Also, his impatient fixation on the music denotes a fascination with such ambiguity. Purgatory, in Elgar’s story, is the destination, not – as usually held by Catholic belief – a liminal space, neither damnation nor salvation, but a place for almost interminable waiting. But something about this appeals to Stephen; if he holds fast to Christian principles for a large part of his story, then he still has a boundless imagination, and we see the unsettling beginnings of his reckoning with such unorthodoxies. It’s an often painful experience for him, and we follow him through this process, watching his journey take place.

At school, we see Stephen championing his version of Christian principles during a classroom debate, battling through his schoolmates’ indifference by fostering a kind of determination to speak a narrow version of his truth. He rejects any incursions on his chosen mindset, but there is no joy in it: Christianity, to him, seems to be a way of hanging on to endangered principles, or rejecting the unpalatable. The more his friends laugh and his masters regard him with a sort of jaded indifference, the more he clings. And he proclaims his pride in England’s free press, unarmed police, freedom of expression – before dismissing a recent documentary on the life of Jesus as ‘atheistic trash’. Stephen is prone to feeling destabilised, but fascinated – secretly, for now – with more ambiguous worldviews. The Dream of Gerontius is an important one of these but, in its way, a gateway to other, as-yet more subversive shifts. The young man we encounter at the beginning of Penda’s Fen is trying to navigate a relationship with his peers and his family, but grapples with sources of anxiety which needs must disrupt his as-yet conservative path.

It’s telling that Stephen, as much as we may sympathise with the unpalatable options swirling ahead of him, is made into quite a snappy, socially awkward, even unpleasant young man at the beginning of the film. Returning to our first introduction to him – playing Elgar in his room – he is rude to his mother when she asks him, quite simply, to turn the music down. He’s no shrinking violet in his unhappiness, either; at school, he has a superior air to him which we learn isn’t really warranted by his academic, sporting, musical or social performances, these being the criteria which an old and established school such as the one he attends would value. He does not excel here; however he snaps at his peers, or talks over them, correcting them, or tries and fails to respond in kind to their mockery. He has an especial kind of antipathy towards one boy in particular, but as it transpires, this opens up the film to a whole new aspect of Stephen’s current difficulties. This is a bullying situation, one which hardly looks out of place in this place and at this time, but Stephen’s dreams and visions reveal sexual attraction to this boy – a kind of attraction/repulsion, no doubt, as being homosexual certainly doesn’t fit in with the first Stephen’s worldview, particularly given the film’s timeframe and setting.

Yes, about that: it’s interesting, and one of Penda’s Fen‘s great, destabilising triumphs, that only towards the very end of the film does it reveal it’s actually set in the 1950s. The story has all the hallmarks of being contemporary with when it was made in the 1970s, from the record player Stephen is using to play his beloved Elgar at the beginning of the film, to the haircuts, to the political views we hear spoken by other characters in the drama, most explicitly by the rabble-rouser Arne. It all feels very Seventies. The sudden and unexpected arrival of a new, strange, fixed point in time, close to the end, sends a shiver through all which we have seen up until that point, disrupting it: what is real here? In that, it gifts us two things: a feeling of kinship with Stephen, who is navigating the same feelings of uncertainty, whose progression we have witnessed. We, as the audience, have to grapple with the same sensation of multiplicity throughout Penda’s Fen, a sense that nothing is as it seems. The whole film is a kind of artistic, dreamily-distant coming apart of certainties; this is also something perfectly in keeping with one of the film’s messages – that certainty can never be. The grind and flux of modern life is always threatening something new, something which must be accommodated and understood. You could argue that it’s this idea which gives the film its title, and serves as its prime mover.

“Some hideous angel”: England in the 70s

You could furthermore argue that, long before the film mentions its actual date and time, we could feel convinced that we’re actually in the 70s thanks to one of the film’s characters in particular. And, in keeping with Stephen Franklin’s early antipathy to anything outside the rather narrow trammel he has at first seemingly chosen for himself, he reacts with a mixture of confusion and hostility (mainly hostility) when he first hears local playwright Arne (Ian Hogg) speak, at a community meeting being held in response to concerns about the impact of long term strikes – striking having become, you could argue, a kind of short-hand in the UK for referring to the 70s themselves, even though high profile strikes continue to feature in the political landscape, and indeed are ongoing into the 2020s. At the meeting, it’s clear that Arne’s perspective is, at least in the small town of Pinvin, a minority view, but regardless of that, he seems to speak for a whole wave of shifting, modernising social and political sensibilities, able even to find voice here, of all places – in this superficially barely-changing place. Arne holds forth on a whole host of topics whilst he has the floor: his speech has notes of profound concern, but also anger, too. In that at least, he’s similar to Stephen Franklin. It’s also interesting that both Stephen and Arne each enjoy a debate, and we see each of them speak to a largely resentful or even hostile audience; it’s just that they are coming from markedly different standpoints, and it must be remembered that Arne does not encounter Stephen’s arguments in any detail, not being privy to the closed-off environment in which he does his own speaking. Outside of military school, the world at large is responding to current affairs – the spectre of strikes and their impact on the wider community is clearly being felt here, and seen as important enough to draw a crowd on this particular evening.

Arne’s speech is one of the high points in this film, showcasing writer David Rudkin’s tremendous lyrical skill (Rudkin also worked on Lawrence Gordon Clark’s seminal TV version of M R James’ The Ash Tree in 1975). Arne is second only to Stephen himself in terms of air time, and when he speaks, he holds forth on a whole list of contemporary concerns, stemming from the strikes, sure, but taking in far more issues too. High on this list are changes to the precious landscape; he alludes to the perils of new construction either on, or beneath the earth, being ostensibly done – as he has it – to shelter people from nuclear attack, though the whole project is presented as somewhat ludicrous, a ream of shelters inaccessible in the maximum ‘four minutes’ warning which would be given, the population probably “strategically expendable”, with all that would be left an array of desks, and pencils, ready for a needless, laughable bureaucracy buried under the earth (a little like the one in Threads, made a decade later).

There are other, very 70s-centred concerns: we hear about more general political turbulence, an increasing sense that modern politics is corrupt, with money being wasted on what Arne refer to as, “bungles, deliriums and fantasies”. Well, quelle change – you could argue. Much of what Arne says feels like strangely prescient environmentalism, too, criticising what is sometimes called ‘late stage capitalism’, though it’s wasn’t a term in common use then, and indeed environmentalism as a movement was in its infancy, or associated only with fringe thinkers and groups. But Stephen, on hearing all of this, reacts with anger: he has perhaps never heard such views, calling Arne a “terrible crank”, and even volunteering the opinion – which he later retracts – that perhaps it’s ‘God’s will’ that the Arnes haven’t been blessed with children. They would only pollute their children with their ‘unnatural’ values, after all. It’s an unpleasant thing to say, and it smacks of Stephen’s deeply-held but brittle position, which is already starting to feel under attack the more he begins to consider his own place in the coming world outside of military school.

But perhaps, on some level, Stephen agrees with some of Arne’s concerns. He, too, is thinking of his place as a kind of child of England, and he too is beginning to see England itself as an inheritance, something to cherish, to hand down. The fear of leaving “nothing but dust” for future generations is shared by both Arne and Stephen, even if Stephen’s response to this fear is wholly different at first. Significantly, having heard Arne, Stephen seems to begin the process of moving away from his incredibly closed, unmovable interpretation of faith, what his schoolmaster links to Manicheanism, a spiritual battle between dark and light – a tempting array of symbols for Stephen’s fracturing conscience, clinging to archetypes and old certainties. Perhaps, whatever else Arne says, and whatever else horrifies Stephen at the beginning of the film, it should be remembered that Arne’s concerns are age-old, because the land itself, the place is also. The whole film plays with the idea of permanence and change: were the contemporaries of this film, in the 70s which are the 50s, poised on the brink, like the barely-known figure of King Penda, the last pagan king of the Mercians, who gives the film its title? In Arne, the film has a spokesperson for a wide array of twentieth century concerns, though in keeping with the overall tone of the film, many of these feel age-old too, somehow. Surely some of his ideas could have been King Penda’s, himself poised on the brink of irredeemable change and transformation.

The land has always had its champions, and in Arne/Stephen Franklin, we have two at first very different kinds of champion, eventually reaching an accord, an ability to share their perspectives. This is, for Stephen, borne out of a painful series of experiences. Again, like Penda, knowledge is hard won, and can only be resolved through acknowledging change, reclaiming the notion of Englishness from parochial ideas and short-sightedness, even if this shift is difficult. In this, Stephen Franklin is reborn, and we leave him in a happier place at the end of the film. However, Penda’s Fen leaves its questions lingering in the air too, reminding us of the ongoing struggle between change and permanence.

Visions, dreams and the unreal

Stephen’s personal progression from recalcitrance to something else entirely comes to us not only through ‘real’ events, but imagined ones. Conversations with his parents (who crucially reveal, on his eighteenth birthday, that he is adopted) and through his admittance of respect for those who do not share his world view (the Arne family) are vitally important, but the kind of mental sorting and sifting necessary to all of this relies quite heavily on the imagined. Visions and dreams in Penda’s Fen are very revealing, often oblique – but sometimes clear enough too, shockingly so for the times perhaps, blending aesthetic and sexual longing with religious iconography and painful moments of reckoning. We see classic, Fuseli-inspired nightmares and homoerotic fantasy. Stephen’s dreams of his school tormentor, naked, create a strange, slightly feverish blend of wish fulfilment but perhaps revulsion too; Penda’s Fen is at times a story of agonised sexual repression as much as a spiritual journey, because in truth, it is in accepting certain truths about himself that Stephen begins to blossom. Beyond more conventional dreams, though, we also witness periods of what must be visions or hallucinations – all of which blend into the story as a whole. These can be more challenging, showing Stephen grappling with difficult and complex ideas.

Elgar is not only notable in Penda’s Fen for providing a musical accompaniment and a certain set of themes; he appears in the film, too, albeit not as a titan of music or creativity, but as a questioning figure, a mortal man asking for reassurance. Stephen’s dream, or vision of a meeting with his beloved Elgar starts on a strangely sour note: no straightforward, spiritual story or meeting of minds, this. Elgar seems preoccupied with his own worldly affairs, in ways which catch Stephen a little unawares. At some detail, he recounts to Stephen his surgical ’embowelling’; nothing could make him seem more human and less easily-exalted than his anecdote of watching his doctors at work: Elgar did indeed die of colorectal cancer, and believed – like the elderly couple in Penda’s Fen, discussed below – only in a grand nothingness after death.

However, the great man does move onto topics which link Stephen’s love for his music with Elgar’s own timelessness, itself an afterlife. Penda’s Fen as a pastoral is beautiful enough, but the film works hard to imbue the beauty of nature with something more profound and permanent. As Elgar moves on from his story of his illness, he speaks some of the film’s most poignant lines. In discussing a potential ‘tune’ for his Dream of Gerontius, he shares a confidence with Stephen, before telling him, “If on the hills you ever hear the sound of an old man’s whistling in the air, don’t be afraid. It’ll only be me.…come back to look at the world, you see. The lovely world.‘ Elgar’s focus for part of his conversation with Stephen is on his death, the indignity of the end of his story. Why does Stephen fixate on this? Is he reckoning with the fact that even exalted men must die? That their courses do not run smooth? Whatever these questions, there is redemption here, redemption which slowly begins to draw Stephen into a new understanding. Other dreams, themselves disturbing, begin to yield up something like hope, too.

Stephen’s spiritual journey – which sounds hackneyed, but is a significant part of the film – is no less complicated. For one, his growing interest in the idea of Manicheanism is, perhaps surprisingly, one of the notions which begins to loosen his grasp on a narrow, unmoving Christianity as the only way to light his way forward. Not that his religious faith dissolves; rather, he begins to see Jesus, his saviour, as part of a multiplicity, all of which point towards a bigger battle for spiritual salvation. Perhaps nothing is as it seems, even when rendered down into light and dark, good and evil. Stephen’s discovery that his own father has written a book on what he sees as the political exploitation of the figure of Jesus (a book which Stephen finds out about by chance) is another moment of destabilisation for him, but again, he is starting to figure out a more sensitive, exploratory means of exploring his faith.

Ultimately, what is faith for, here? The early version of Stephen uses it as a shield, deflecting any alternative world views, hiding from the parries of a world which feels increasingly hostile. But faith is more malleable than he first allows, and – as it turns out – his rector father understands this very well. The film includes a moving, thought-provoking sequence from the rector’s daily life, as he calls on an old couple, now faced with death. They have quietly rejected hope in an afterlife, preferring instead to count (and revel in) their ‘days allotted’. But the rector is there with them at the end nonetheless, and the older woman accepts this without issue: he is not sent away from the bedside, but cherished for his humanity. The rector, who feels like a remote figure at the start of the film, undergoes a journey of his own here, eventually enjoying a newfound relationship with his son – his son, regardless of the fact that Stephen is adopted, and not ‘chemically’ related to him, as Stephen puts it. The rector reveals himself as a caring, considerate and tolerant thinker, a comfort as well as part of the fabric of the community. He is a parson in a small village in 1950s (1970s) England, but he is not confined by any one worldview, and is now able to foster an equivalent, broad worldview in Stephen, a young man who has undergone a dark night of the soul, with angels and devils contesting for him. And, finally, it’s perhaps suitable and inevitable that Stephen’s last act in the film involves an extended vision, and another tussle over him: his body, his mind, his morals.

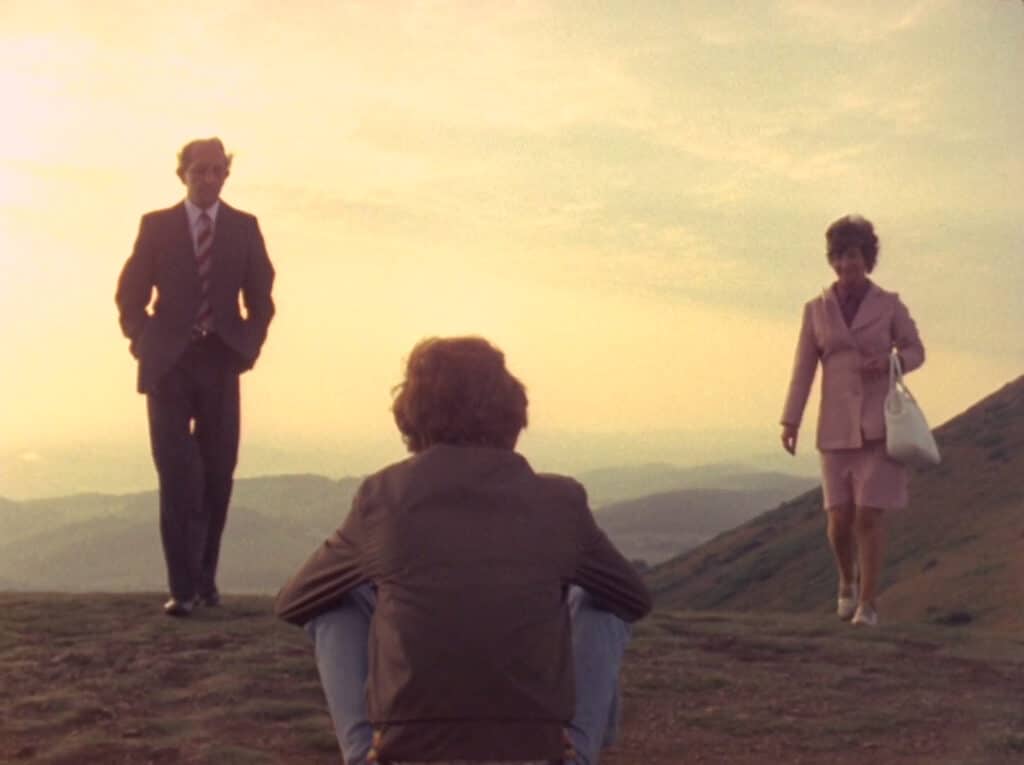

The older couple who approach him at the end of the film seem representative of establishment, a kind of timeless conservatism perhaps that, in always looking back, looks only at a tiny point of light on the receding horizon. And they argue over Stephen, in an incredible, if densely-layered scene: they offer him wealth, power, but point out that to attain all of this is to “be put to the fire” like Joan of Ark, another figure mentioned in Penda’s Fen. It speaks to purification, to ascend as a ‘child of light’ – but Stephen, as the end of the film, is able to reject their unequivocal spiritual truths, displanting them for some of his own, hard-won, even if perhaps an earlier version of himself would have wholeheartedly sought the same blanching of his sense of self. It’s a defiant speech which blurs ideas and boundaries in a way which seems unprecedented given that this film is now half a century old. He responds to the couple’s references to him as ‘a child of light’, and in some ways their inheritance too, in the following way:

‘I am nothing pure. Nothing pure! My race is mixed. My sex is mixed. I am woman and man. Light with darkness. Mixed! Mixed. I am nothing special. Nothing, nothing pure. I am mud and flame!’

Whilst this remarkable speech brings him back to himself, it angers the couple: they would have him a child forever, they claim ownership over him, and would rather sacrifice him than lose him. There are echoes here of one of the film’s other, great strange sequences: the ‘society party’, if you can call it that, where attendees, clad in cowardice-yellow, are happily queuing up to have their hands severed: it’s the ghastliness of social mores and peer pressure writ large. But finally, Stephen is able to defend himself on his own, new terms. This suggests what the whole film has hinted, that spiritual growth requires a kind of casting off of the received wisdom that the couple, as representatives of the world Stephen tried to occupy, value. And, finally, we meet the figure who is vital to all of this – the vision of Penda himself, enthroned and overlooking his ancestral lands, his ghost permeating through time to overwrite itself on the landscape by giving it a name.

“Unbury me…”

But who is Penda? What is Penda’s Fen, exactly? Stephen’s journey towards a meaningful identity of his own draws upon history, language and literature as it goes, so that even the town he has always known takes on a new identity, the village name, Pinvin, being a corruption of the Anglo-Saxon name ‘Penda’s Fen’ or Pendafen’ – the hard edges of the place-name eroding steadily over hundreds of years. But the place is the same, and King Penda – the last pagan king of England – may himself have experienced the same harrying of his worldview, the same spiritual struggle poised between loss and understanding. This consideration grants us the greatest monologue in the film, as spoken by Stephen’s adopted father:

King Penda. What mystery of this land went down with him forever? What wisdom? When Penda fell, what dark old sun of light went out? Pinvin. Pin-fin. King Penda’s fen. Did Penda die here? Who says that he is dead?

Penda is not the only historical figure who becomes interwoven with the story here, but he gives his name to the film and he survives in the bucolic landscape which still bears something of his name. When the rector asks if he is ‘dead’, he is perhaps thinking of how the old king has become part of the fabric of England, of place, all while the world view which Penda would have fought for has disintegrated. Pagan England is long gone, but the same cruelties persist; how did Penda, at the end, resolve these contradictions?

He goes some way towards telling us personally. Penda himself appears to Stephen at the close of the film, tasking the young man with a legacy he has not understood until now. It is a beautiful, poetic episode, from a man known and unknown, and there is parity: Penda’s England sinking without trace, Stephen’s world on the brink of madness and disintegration, as clearly described by Arne. There is a kinship between them, and an appeal by the old Pagan king. Again, it is worth letting these lines of Penda’s speak for themselves:

‘Our land and mine goes down into a darkness now. And I, and all the other guardians of her flame are driven from our home, up and out into the wolf’s jaw. But the flame still flickers in the fen. You are marked down to cherish that. Cherish the flame, till we can safely wake again. The flame is in your hands; we trust it you. Our sacred demon of ungovernableness. Cherish the flame; we shall rest easy. Stephen, be secret. Child, be strange. Dark, true, impure and dissonant. Cherish our flame. Our dawn shall come.’

Conclusion: ‘And did those feet in ancient time…’

Penda’s closing speech is, I think, about hope, whatever the adversity. Penda’s Fen steps dreamily but decidedly away from cast-iron resolutions, but offers greater happiness and understanding to people willing to challenge received wisdom, to reach profound understanding of their own, often by looking again at establishment truths, arranged into hierarchies and systems which can harm. The threatening spectre of nuclear annihilation was a new ghost to contend with in the 1970s, and was by then itself entrenched, shaping the actions and unease of millions. But by scale, the new world which felled King Penda was the end of a world, too. And then, personal crises, and personal considerations of how to live one’s life; these have been a constant. Change is a given, but how to navigate it?

You could even argue that the film’s unexamined relationship with visionary writer and engraver William Blake could give us our clearest parallel to Stephen Franklin’s own journey, and it feels entirely in keeping with the tone of the film overall that this is never made explicit, other than that Jerusalem, penned by Blake and set to music by a contemporary of Elgar’s, Hubert Parry, appears in its role as unofficial English anthem, being sung by rows of boys at Stephen’s school. This song appears as one of the fixtures and fittings of repressive school life here, and may mean nothing more, but consider it further: Blake was a pioneer, a man who himself negotiated a new relationship with God and with faith, a man whose own religious sentiments broke sharply away from the commonly-held ideas of his own peers.

Blake saw visions, conversed with angels, like Stephen, and saw them often, something which he noted down as simply part and parcel of his own spiritual progression, even whilst it confused and alarmed some of those closest to him. His work, too, was deeply influenced by the changes he saw taking place around him as the Industrial Revolution took hold. His Songs of Innocence represent a dwindling but potent ideal; his Songs of Experience retrace many of the same themes but re-written, bemoaning the fates of the poor, of children, of the natural world – but through the Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience there is a clear progression, from innocence into experience, with all that signifies. He would likely have nodded at Arne’s warnings too, and echoed his sentiments. As a spokesman for the poor and downtrodden, he would have likely supported striking workers, as he was present in the crowd which burned Newgate Prison in 1780. The established Church was, to Blake, an ineffective monolith, doing little to ease the lives of people dependent on the mercy of such institutions and unresponsive to the questions and duties being asked of it. Likewise, Blake’s ideas about the other, great certainties of his society – including sexuality and marriage – were unorthodox, too.

Perhaps the path taken by Blake, his avowal ‘not to cease from mental fight’, mirrors Stephen’s own path – or maybe there are simply countless examples of men throughout history, known and unknown, Christian and pagan, of unclear heritage or sex, whose steps are being retraced here. However, in a film rich with historical characters, there does seem to be one whose own experiences are at least half-reflected here.

Penda’s Fen is a film of contrasts: it’s gentle and yielding, a beautiful pastoral, a coming-of-age drama, but it’s also complex and at times sinister. In different hands, it could have felt whimsical at best, absurd at worst, but as directed by Alan Clarke it feels clever, ambitious and profound – testament to his great caution and skill in bringing the screenplay to life. It’s a challenging project. It frequently detaches from time, even if not place – place is a permanent feature, but it’s a palimpsest, constantly being re-written by new thinkers, or hacked apart by crises. And, just as it uses dreams and hallucinations, so it feels like one, with Stephen’s symbolic monsters and visions hazily representing something to us, too, which may feel just out of one’s grasp but still oddly vital. Penda’s Fen feels ultimately very intricate – familiar but distant, a dream of England where shifting, liminal ideas wander forward to some kind of new understanding. That it’s now half a century old is truly remarkable.