It’s a strange thing – I was prepared to write this review of The Frightened Woman as if this film is nothing more than a quirky time capsule, a pretty, picturesque piece of cinema coming from some very particular social and cultural mores. Of course, it is all of that, but its story of a wealthy philanthropist working through his frustrated misogyny on the weekends isn’t something we’ve exactly left behind us, is it? It’s too much to say that director Piero Schivazappa was some kind of seer, but he’s certainly, possibly accidentally made a film which can still resonate on some level. That, and a film which is bizarrely good fun, increasing its black comedy elements as it progresses. It’s a lurid, inventive slice of late Sixties gender paranoia, and well worth a look – if you like that kind of thing.

We are introduced to the man of the moment, thrusting executive and philanthropist Dr. Sayer (Philippe Leroy) as he’s in the process of chastising a light-fingered colleague. There’s just been a meeting to decide what to do with him; Sayer warns him that he’s lucky to only get expelled, and not given a criminal record, too. Aggrieved, our thief (who has just nicked a golden letter from a commemorative bust, just to make the point) lingers for a moment when he glimpses one of the organisation’s other employees – a young woman, Maria (Dagmar Lassander). The film is choc full of this kind of furtive watching. Maria, as it turns out, has business with Sayer too, visiting his office to ask him for some documentation which will enable her to complete a report on ‘male sterilisation in India’. How the chilly spring evenings must fly! Sayer, surprisingly and instantly hostile at the very notion of sterilising any man (I suppose if you’re philanthropically minded, this can extend to other men’s gonads) nonetheless agrees that she can have the material she needs, but she needs to collect it from his house. Safeguarding hadn’t been invented then, which is a boon for this type of cinema.

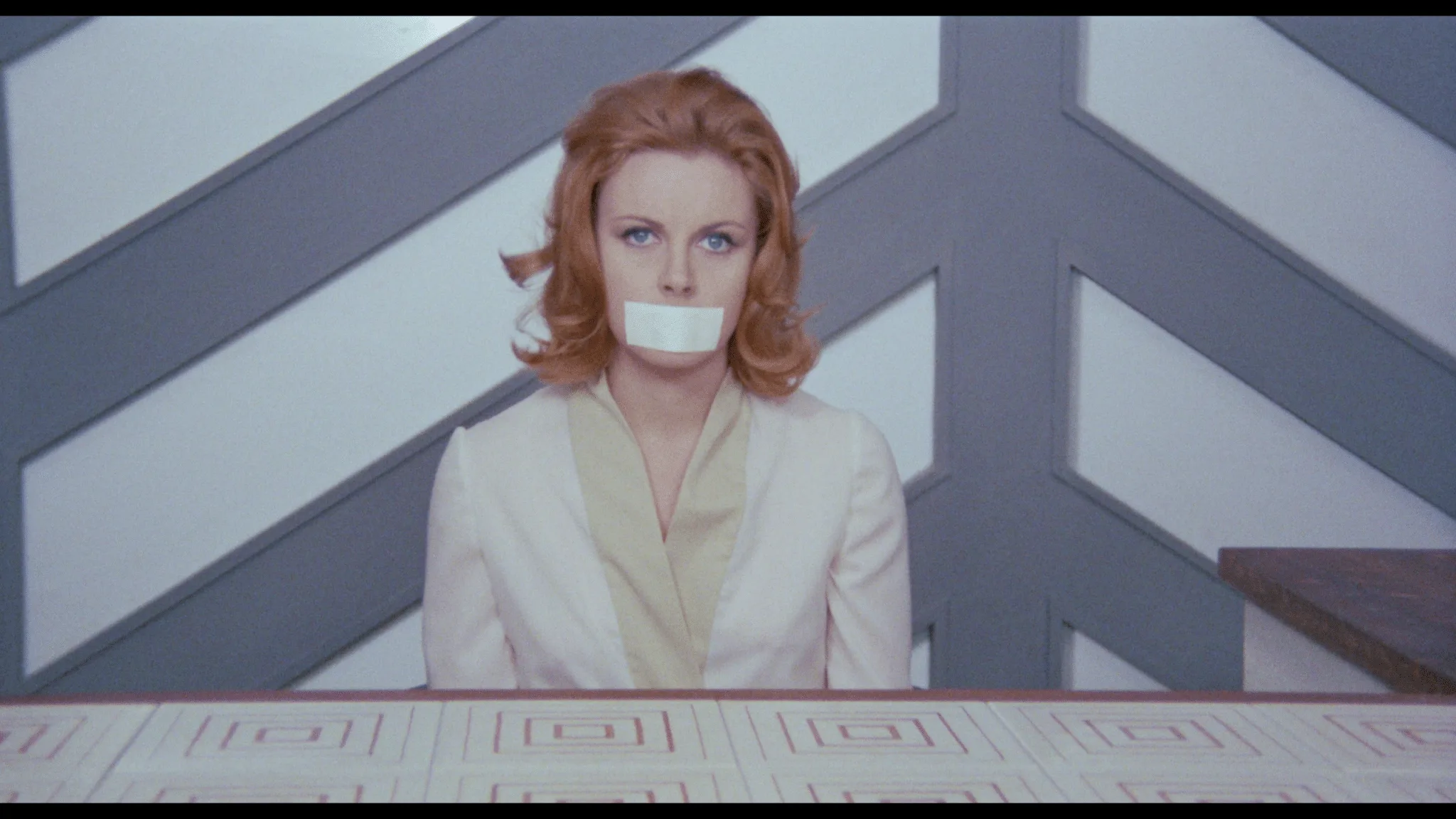

Maria goes to Sayer’s house as arranged; little does she apparently know that the working girl witnessed in the very opening scenes has a link to Sayer, too. So far as Maria goes, as they exchange a few vocal parries and as he offers her a standard-issue glass of J&B, she quickly slips out of consciousness, waking up restrained and being observed from a distance by a glowering Sayer. He begins to expound his philosophy, which seems to have been triggered by a horror of women’s desires to be self-sufficient. This cannot be; he envisages a future where males won’t be needed at all, and he’s appalled. His response is to double down on old, entrenched gender roles, resetting the clock by tormenting women, making them feel extreme fear. It just so happens that Maria is now the woman in the frame, seeing as Sayer’s original plans have come to nothing. She’s his new captive.

A series of warped domestic scenarios hereafter merge with weird and wonderful set pieces, as a rather literal battle of the sexes emerges. Sayer is clearly very practiced at this, and depends on such strictures in order to enjoy any sort of erotic interest in women; however, whatever kind of schedule he has used recently has perhaps met its match in Maria, who may make it look as though she is – begrudgingly – playing her role in Sayer’s strange set-ups, but is rather more worldly than he gives her credit. She’s watching and observing, and wants to turn things around to her favour. The film uses an often ingenious and ambitious structure where its worst, most sadistic scenes get repeated later with a different emphasis, as each key player here has a different modus operandi. It also manages to sustain a few different shifts in tone, moving from straightforwardly nasty to gently teasing and even funny, intentionally funny, even as a whole host of anxieties and nervousness are explored.

Most of all, though, The Frightened Woman is a swirling, heady study of sexual neuroses as they were on the brink of the 1970s, as the feminist movement grew and women did seem, to some, to be edging towards being sinisterly self-sufficient (another film which sprang to mind whilst watching this one was Invasion of the Bee Girls (1973), which took a similar stance towards the perils of sexually licentious women, albeit with some light-touch sci-fi at its own core). And, as much as The Frightened Woman creates a bit of a pastiche of these men who would now probably refer (to themselves, only ever to themselves) as Alphas, there’s some real-world context pressing in at the edges, and such shifts in sexual or gender roles did, and do, generate a lot of unease. The film plays quite liberally with this.

We also see other thoroughly modern predilections in the film, perhaps most notably psychoanalysis: many exploitation films of the era find time and space to include the talking cure, though perhaps Schivazappa and his design department go one better by building an entire vagina dentata sculpture to emasculate its men. The push/pull between modernising tastes and reactionary retreat leads to a fascinating interplay in this film, as in others of the same era; in terms of comparison with some of those other films, The Frightened Woman isn’t especially gratuitous, nor is it grisly, but it’s heavy on the psychological warfare, a careful and often clever film with a strong aesthetic sense (that house!) and strong production values. This Blu-ray release makes the film look incredibly fresh and surprisingly modern, too, for all of its late Sixties trappings and fashions. It makes for a good visual balance overall.

With extras including two roughly thirty-minute interviews with Schivazappa and with Dagmar Lassander, and a frankly display-worthy new cover design, Shameless Films release this Blu on January 8th 2024. This is good work from them, as always, and an unusual, weirdly inventive piece of 60s cinema for your collections.