In sitting down to put this piece together, something soon became very clear: it’s difficult to properly explain a thirty-year connection with an album – any album. If music – or film, or literature – has been a part of your life for that long, then it’s probably long since become a part of your emotional landscape somehow. The album itself becomes a longstanding feature, sometimes played often, sometimes seldom as the years pass, but always there. Still, as My Dying Bride’s Turn Loose The Swans hits its thirty year milestone, it feels only right to try and explain what it means to me.

This album – the single most influential and important album of my life, it’s no exaggeration to say – has endured for what feels like my whole life; certainly for my whole self-determined years. I was into my teens when I first took an interest in metal, then death metal, then anything which sounded suitably heavy and/or weird. I was, at this point, just picking my way through genres piecemeal with no real understanding of anything and only adverts or reviews in, say, the short-lived Xtreme Noise to guide the way, but this casual approach to picking out titles served me pretty well. I’d recently saved up and bought MDB’s EP The Thrash of Naked Limbs, because the title promised something interesting; there was no finesse to this approach, but nor should you expect that of a kid living in the middle of nowhere with nothing but curiosity to see her through. I also trusted the long-defunct Round Diamond Records not to stock anything other than music I’d not be likely to encounter anywhere else at hand.

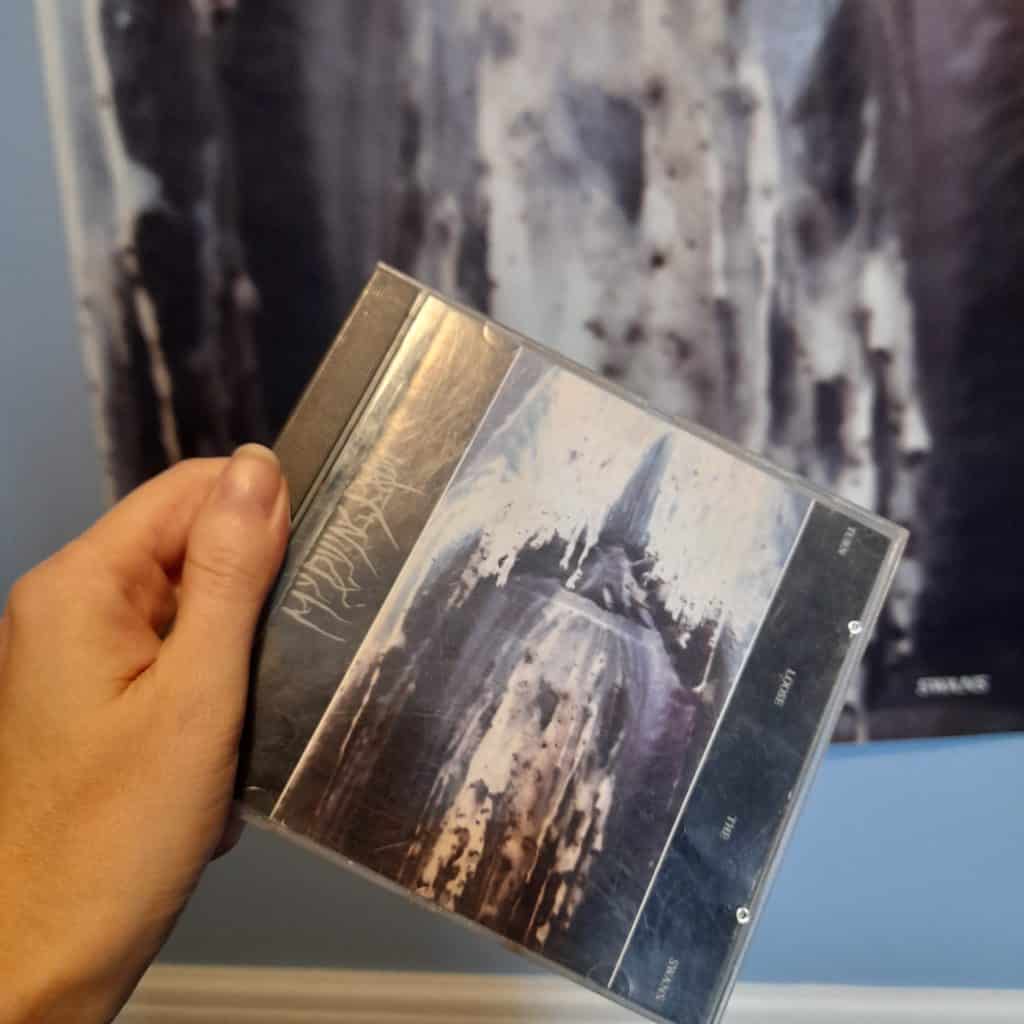

So The Thrash of Naked Limbs arrived, proved defiantly unconventional, was just as Gothic and experimental as I’d hoped, and proved to be a very lucky find. Its (for the most part) languid pace, its use of death metal elements, and – my god – violin, something I’d never even considered could work in music like this, soon had me referring to myself as a My Dying Bride fan. I was a violinist myself at this point, though my enthusiasm was starting to wane: the concept of playing metal, rather than doing endless violence to Little Brown Jug, was a revelation. I started asking for other MDB releases, actually coming to Turn Loose… before I got hold of As The Flower Withers. I had little concept of discographies, either. I heard the Slayer albums in reverse. I had no one to ask, as such. Turn Loose The Swans ended up being a Christmas present the year it came out, and I distinctly remember unwrapping the CD – not vinyl, absolutely not vinyl, which was a couple of decades off its Instagram Renaissance (and I still own the same CD, which I’ve somehow hung onto across eleven subsequent house moves, though the cover has looked increasingly sorry for itself since some point in the Nineties).

Now, despite some experience with the violin, I’m no musician: everything I’m about to say about Turn Loose The Swans comes from my own personal impressions, so if I misspeak or misdescribe a musical term or sound otherwise clueless, it’s coming from a place of blissful ignorance. But I’m a fan nonetheless, and I do want to try to describe what I got and still get from the album – in effect, I want to try to explain what it means to me and how I feel when I listen. I can only try; whilst different impressions and whilst memories surface here and there upon re-listens, here are some of them.

For a teenager expecting something, if not avowedly death metal, then close to it, the opening track, Sear Me MCMXCIII – the second of three tracks to bear a variant of this title – was, perhaps is, a great surprise. Bookended in musical style by the album’s final track, Black God, it has none of the expected guitar or drums, and certainly no growls. Whilst not overburdened with lyrics, the song nonetheless showcases the dark Romanticism which has been a mainstay for the band throughout its lifespan; MDB lyrics can often tend to be devotional (lots of mentions of God, Heaven, faith) but married to more earthly themes, often romantic or sexual in nature. There’s clean vocals here – clean vocals dominate the album – but vocalist Aaron Stainthorpe intones more than he sings on the opener, with only a handful of lines picked out as melodies: whilst other, later songs on the album do move somewhat closer to more recognisable doom metal, Sear Me is stripped down, simple and striking; it forms a good introduction to what’s coming. It manages to be both ominous, and uplifting; perhaps that’s the band to a tee.

‘We gather thorns for flowers…’

That said, in the next track – Your River – the pared-back instrumentation continues as the track opens up. When the whole band come in, including violinist Martin Powell, it establishes the intensely atmospheric, rising-and-falling tempo which demarcates this album. Next up, The Songless Bird is perhaps one of the more accessible metal tracks on the album, but feels ferocious compared to even the two preceding tracks. The lyrics also undergo a shift, switching from reverence to scorn, even though the song pauses for some of the harmony between guitar and violin which returns throughout. This allows the song a calmer, more sombre section, before kicking back into its higher tempo.

After The Snow in My Hand – a beautiful, plaintive song in its own right – it’s into the two greatest songs on the album, which appear back-to-back. The Crown of Sympathy is an absolute force of nature, and perhaps the band thinks so too, as it was ably remixed on the compilation album Trinity in 1995. The Crown of Sympathy is brooding, heartfelt and pleading in places; is it too much to say it feels like it’s telling a story, confession, last words? It has echoes of Baudelaire in it lyrically, or maybe the Gothic world-building of Angela Carter, which definitely feels like the case in later MDB songs, coincidence or otherwise (The Blue Lotus is very similar thematically to The Lady of the House of Love, for instance). Here, there are more allusions to faith, doubt and loss, and the song shifts from mellifluous dirge into a killer hook. The whole album’s tempo shifts are epic; here they’re sweeping, staggeringly good; this song, and the next are masterclasses.

Which brings us to the title track, and for me, simply one of the greatest doom metal songs ever created – and we’re talking Yorkshire doom here, if we can call it that, which has little in common with the doom sound of the 70s and 80s, thematically or stylistically. The harmony between the opening riff and the accompanying violin is simply beautiful; how could you ever feel nothing on hearing it? It’s also a hugely ambitious song on an album full of ambitious songs – terrifically heavy, but balanced against pauses, shifts, deviations. In some respects, it shouldn’t work, but it works absolutely seamlessly. Black God ends the album on a mournful, sombre, guitar-less note, feeling like the epilogue we need after an album of this scale. Something to settle the nerves, maybe, and if elements of The Crown of Sympathy have a kind of religious, pleading quality to them, then Black God is clearly lyrically modelled on a final prayer. It’s a quiet, but no less ambitious ending to an album which, in just under an hour, has reconfigured a genre, or created one.

‘No sad adieus….’

So what can we say, finally, of Turn Loose The Swans? It’s an album which balances a certain amount of pomp and bombast against far quieter, subtler moments, and makes it work utterly brilliantly. It’s huge and ambitious (the band were only in their twenties when they wrote it) with looming, wholly original songs melding Sturm und Drang with complex melodies and piteous lyrics, then wedding orchestral sections to death metal elements in ways which still seem perfectly effortless. It’s lost nothing of its initial shock factor, either, and still feels like the most coherent, but undeniably avant-garde thing MDB have ever done. Later albums – with the exception of 34.788% Complete perhaps – haven’t played with genre and expectations so thoroughly, and MDB’s doom sound feels more…contiguous, or perhaps recognisable is a better word, after The Angel and the Dark River, which came out just a couple of years later. Turn Loose The Swans is still the boldest album MDB have ever released though, and that it’s able to do so much inside a one-hour runtime (Bell Witch take note) is still phenomenal.

For me, this was the high water-mark of this style of doom metal, even whilst establishing this style of doom metal. Let’s go further: this is the apex of music for me. It made an artform out of a kind of melancholy I’ve stuck with throughout my life, or which has stuck with me, and on an even more personal note, it’s been a bittersweet experience trying to sift through the years and put into words what I first felt then – as just a girl – now that I’m so much older, and now that any genuine affiliation with all of that vociferous, yearning emotion has been sloughed away. But the music is still there, still brilliant, still revelatory, still beautiful. It retains an immense amount of power. Nothing about that has changed.

Will I still be around in another thirty years? Touch and go, let’s be honest! Will the album? Yes it will, in some way, shape or form – maybe playing via technology we haven’t conceived yet – but it fully deserves to have a devoted audience forever, and I’m confident it’ll keep finding its audience. I’m just one of the first of them. I’m still one of them. And I’m immensely grateful.