By Gabby Foor and Keri O’Shea

We were delighted to be offered Fantasia’s short film blocks for coverage again this year. Small Gauge Trauma, the festival’s genre short film collection, is a great way to spot upcoming talent, clever homage, brand-new ideas and ingenious storytelling. As ever, the range has been incredible, with everything from your more typical vampires and ghosts right through to mind-altering slugs (oh yes), Cronenberg-akin machine projects and puppeteers. Without further ado, let’s round off our festival coverage on a high; we still have Born of Woman to follow, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves just yet.

In fact, though, perhaps we have got ahead of ourselves a little. Starting off Small Gauge Trauma this year is Transylvanie, which we have already covered at the site. For more on this cleverly-crafted and charming film, which blends its vampire iconography with the emotive, ambiguous likes of Let The Right One In and Martin, check out Gabby’s review here.

Next up, Cover Your Ears (dir. Oskar Johansson) picks up on a concept which has run like a seam through a certain subset of horror in recent years: sensory deprivation. Here, however, the protagonists elect not to hear, for reasons which the film reveals – to chilling effect. Two young women – who seem like sisters – live alone in a grand house. The film starts with one of the girls accidentally smashing a plate; the other girl looks on as she clears away the pieces, but it’s one of the film’s first jarring moments of high sound. There’s something strained, if still loving, in this relationship. In particular, when it’s time for bed, the girls put on noise-cancelling headphones: why?

This film creates a keen sense of the uncanny with its neat, careful touches. Inverting shots, or inverting what is being filmed, quickly serves as an alarming, if simple enough motif; we’re also locked out of the film’s only dialogue as if we, too, are wearing the headphones, which keeps us uncertain of the film’s rising threat (though rising strings in the film’s soundtrack – prior to also falling silent – raise those hackles). With its close, unerring focus on the protagonists and their own rising hackles, this is an effective horror which only tantalises a story, but does more than enough to generate an atmospheric scare. [KO]

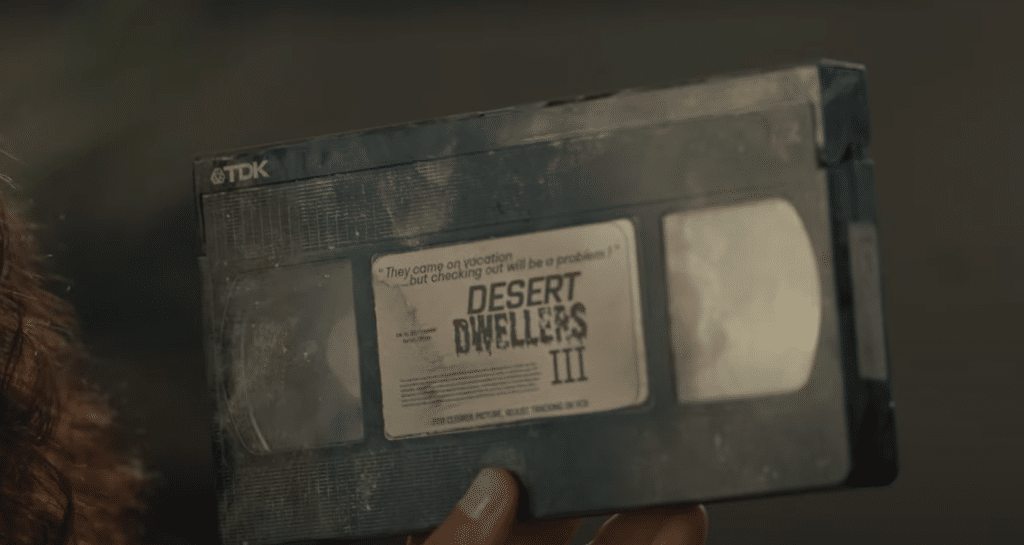

Get Away (dir. Michael Gabriele) shows us three young women arriving at a remote getaway in the desert for some well-deserved downtime. Deciding to take it easy and watch a movie, they’re charmed to discover the lodge’s VHS player and its single viewing choice: Desert Dwellers III, which looks like a low-budget horror (and it is). As they begin to watch, the plot begins to look oddly familiar…

What follows is a high energy, often upbeat-feeling horror of its own, nicely paced, nicely constructed and with lots of fun layering and mirroring. Whilst at first the script’s focus on the girls’ ‘no phone signal’ chatter seemed to be having a little too much made of it, it becomes clear that it’s there because the film is being self-referential, playing with tropes and ideas throughout. The idea of the creepy video tape has certainly been with us long enough to feel like part of our heritage at this point, and it gets a good outing here (which feels like Resolution (2012) in some places – and that’s certainly intended a compliment). [KO]

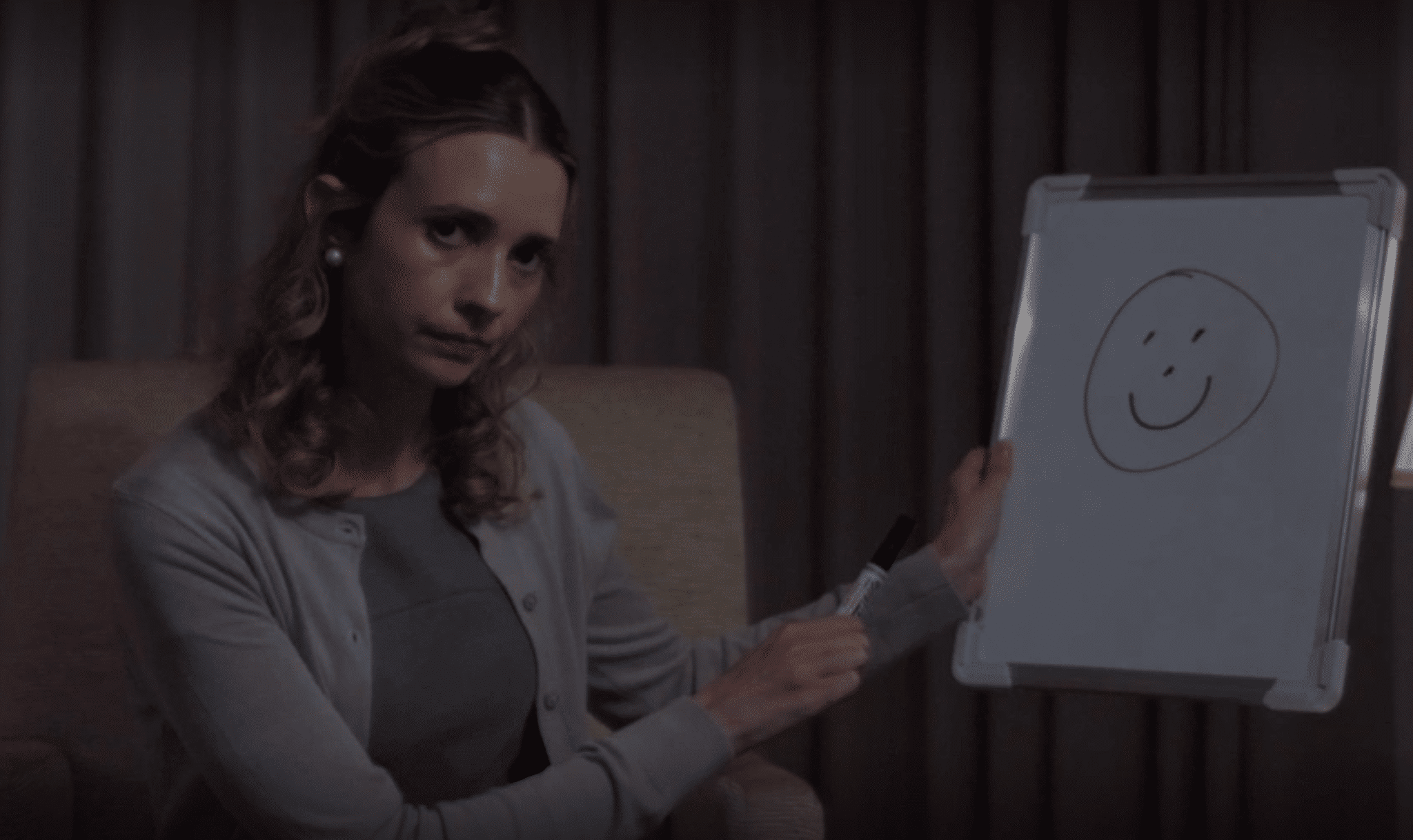

The Nolberto Method (dir. David Winstone) brings the ridiculous and the sublime into record-breaking levels of conjunction here: it’s dark, it’s sharp and it’s very good indeed. It works on multiple levels too: you can drill down (heh) from its humour and its madcap plot elements into something far more profound, into ideas about personhood, personality and one’s place in the world. It also feels, for all its reference to a distinctly foreign influence, undeniably British.

We start in a therapy session, where a clearly depressed man, Darius (Adam Loxley) wants to pour out his heart to his smart, detached therapist. But she stops him: this in itself blindsides Darius, who clearly has certain expectations on how this is all going to go. His counsellor Anika (Sarah Beck Mather) runs him through a few questions to see if they can ‘proceed’ with a radical new treatment. Which relates to a slug. A very special slug. What ensues is dialogue-rich, with jet black humour and excellent performances. There’s some mockery of therapy tropes, some on-point understanding of depression and its contested nature, but ultimately The Nolberto Method crosses from this into a study of selfhood which begs important questions, even if it does it obliquely. [KO]

Next up, Puppet Man (dir. Andrew Fuchs) has its own novel take on trauma: here, reality and unreality are blended together in a sad, meticulous and at times emotionally devastating story. Sal, our puppeteer is about to go to work. He seems to be literally patching himself up before the show, and he seems troubled, down-at-heel. No matter; it’s on with the show, which is titled ‘Tinkerbell’. It all seems to be innocuous enough, right up until the puppets speak their first lines: anthropomorphised animals they might be, but their yearning for love, support and belonging bleed into, and are bled into by the puppet man himself. How much of him is in this? Things blur even further when he tales a phonecall during the performance.

In just fifteen minutes, Puppet Man creates a thought-provoking character study which interrogates the relationship between performer and audiences, as well as between performer and performance. We are invited to determine where one of these things ends and the other begins; in its way, the film suggests that in some cases, they overlap in ways which are impossible to separate. This is an inspired piece of world-building. [KO]

Next up: Role Play (dir. Bill Neil). Having made trailer edits for decades prior to beginning his own filmmaking efforts, director Neil here brings us one of the most compact films of the festival. Fitted with all the trappings of stranger danger and with nods to queer and feminist horror, this story of a one-night stand turned into a nightmare is a small offering of the disturbing to the outright terrifying. Two men are returning to an apartment after a night out, kissing and stumbling in the door. One is older, dressed sharply in business attire with a serious demeanor; the other is a younger man dressed casually and clearly intimidated by his seemingly more experienced and intense partner. After some teasing around the older man suddenly proposes the two engage in some role play, cutting off the flirtation. Surveying the apartment, lofty and expensive with a magnificent view, the younger man is distracted while the older one disappears up the stairs, warning the young man he will need a “safe word” if things get intense. The boy laughs it off as dramatic effect, but as he ascends towards the bedroom, what awaits him can’t be stopped by any safe word.

The setup of the role play itself is terrifying and brilliant, keeping things hidden and letting tensions build as predator and prey are identified and separated. Lighting tricks and practical effects make an unsettling reveals just as intense as promised, with practical effects, creepy attire and gestures. Both men play their roles conservatively well, with neither needing to deliver an over the top performance as their exchanges are cryptic and short; the abomination and subsequent experiences awaiting our victim cannot be described in words. With some feminist and queer horror overtones that always warn you about the perils of the unknown and the risks of taking an enticing guest home, Neil acknowledges the dangers for marginalized groups to be more easily preyed upon. The idea that this is all, in ways, for fun, makes it more frightening, as only one party controls the rules of play, making this even more about power and evoking fear. The fate of both characters hangs in the city skyline that lingers in the final shot, the happenings of the evening condensed into a traumatizing blur. You might come to understand only a few things about the older, more mysterious of the two gentlemen, but the impact of this knowledge is enough to leave you wanting more. [GF]

At just over six minutes, Stop Dead (dir. Emily Greenwood) presents many concepts and references that add up to a terrifying ultimatum for anyone caught in its web. With echoes of It Follows, this film takes the stalking entity angle and keeps the stakes high. Beginning with two officers on a stop, one obviously more business oriented than the other, it looks like a slow night in rural country for the pair. From out of the darkness into the squad cars headlights a girl emerges, dirty, dead faced, and slowly inching her way forwards, each step looking more exhausted than the last. The officers move to call it in, and they attempt to approach the girl and offer help when she suddenly gets violent, drawing a weapon, saying she cannot stop, even under the threat of being tasered. There’s something worse in the woods than guns drawn at her, and she would do anything to keep moving.

This simple concept plays off of It Follows very well: you’re safe so long as you keep gaining ground. The origin of the entity here is less fleshed out than in It Follows, but its design and movements make it terrifying, mimicking the chittering and erratic movements of The Babadook. This entity makes it clear that as long as you’re moving, you’re safe, but the consequences of defying its rule are horrifying. Impressive and unexpected practical effects burst forth suddenly and turn this terror into an all-out nightmare once you’re presented with the fate of those that cease to move. Leaving the characters in a life or death position where they are forever on their feet, this entity is relentless and daunting as it mocks them, defying time and space with its movements, constantly looming. [GF]

House arrest is one thing, haunted house arrest is another in Incomplete (dir. Zoey Martinson). It’s a truly chilling, compact, nail biting tale of one man’s confinement, much to my horror and delight. If you’ve seen the old cult classic Housebound, you may be familiar with the idea of a person confined to a house with unexplainable happenings and the desperation to escape. However, as part of the Small Gauge Trauma portion of the festival, this is a much shorter, darker story with less precious time to uncover secrets. In this tale, a young man (Marchant Davis) has been confined to his home on house arrest, supported by his sister, and bound by check-ins from a caller labeled “Overseer.” A constantly beeping machine prompts him for a breathalyzer on a schedule, marking him “incomplete” even on occasions when he completes the test. With the machine going haywire, mysterious shadows manifesting, and nowhere to go, it looks like our prisoner isn’t in solitary after all.

The plot device and minimal but efficient use of effects used to reveal the paranormal activity is brilliant, and the director waits the perfect amount of time before dropping the hammer of how terrifying the realizations are. Davis is a perfect lead, emotions pitched high, scrambling and bargaining to try and find a way out of this hopelessly frightening situation without permanently jeopardizing his freedom or losing his sanity. The gentle build-up to the shocking realization of what’s been happening makes the blow all the more creepy as we come to see how sinister the presence is. This short film fits neatly into the haunted house genre, while managing to stand out amongst a crowded topic saturated with unoriginal tropes and effects we have seen too many times before. Martinson sets out to break clichés with a tiny cast and inventive horror and dystopian-like devices that zoom in on all the things that make you squirm. [GF]

The existence of ghosts has always been, and may always be, in question. Spirits have been represented in all forms of media, and some claim to have seen the real deal, but in There Are No Ghosts (dir. Nacho Solana), we ride a gray line involving the undead that I haven’t encountered before. Beginning with an old woman having a late-night beverage, we hear all the tell-tale signs of a haunting: whispering, moving, footsteps coming from every angle. When the woman is finally shocked out of her trance from the fear of the events, we cut to Andrea (Catalina Sopelana), whose phone is ringing off the hook. Andrea has a gift: she is in tune to the things most people can’t see or hear from the other side and offers her services at no charge to families experiencing paranormal activity. After receiving a call to go to the old woman’s house, Andrea is on her way to hunt down what may be tormenting the old woman.

With no special or practical effects to generate spectres, the audio design of footsteps, whispered messages, and general haunted fare falls to sound editor Sergio Ausin Belmonte. This unique design, despite its lack of classical ghost scares, still lends itself to the haunted house or ghost hunting genre easily. Ghosts are… less concrete in this world, and in very Latin fashion as I was taught growing up, they’re not always something to fear, maybe something to understand instead. Andrea’s generosity – which goes against everything a generally for-profit medium does – shows deep compassion and empathy as she lays herself and her easily dismissed gifts bare in personal ads, knowing just how taboo the subject is to go seeking help on your own. With nothing but a bottle of beer and her own personal experiences to lead her to the echoes of the dead, Andrea is a serene-faced messenger to those in crisis, even when they aren’t ready to hear the truth. This is a poignant story of ghost hunting devoid of candles, salt and cameras to document the X-Files-like reveal of a spirit. This is meant as a guide to show that all of us are open to echoes from those past; some just tune into the frequency better. I was moved by the presentation of how our dead move on and what they leave behind, as well as by the portrayal of the rare benevolent medium out to help the grieving instead of preying on believers. With a haunting walkthrough of a family’s tragedy through the eyes of someone gifted, you hear the pain and regret of the past and are only left to imagine the history and swiftly ended future of those who leave their messages scrawled behind as they pass over. [GF]

Finally we have La Machine d’Alex (dir. Mael Le Mée) and I’ve never seen a piece of film quite like this before. This a work of psychosexual tension, futuristic fleshy fusion, and a sometimes disturbing, sometimes liberating look at the life of a woman with a passion, and fixation. Alex (Lomane de Dietrich), is the only woman in her “automotive biomechanics” class. A gifted student but one who prefers to keep to herself, Alex is a genius with the engines being created in the lab. They’re a fusion between traditional mechanics and “artificial flesh” that gives the engines a living quality and requires them to receive further, medical-like maintenance. While Alex excels as a student, her attention lies elsewhere with her own personal work. She is designing her own engine—large, intricate, somewhere between a miracle and an abomination of metal and false flesh. Reactive, adaptive, and connected to Alex and her stimulation of it through touch as well as a control panel, the machine serves her needs in many ways and becomes a focal point for herself and for curious others, when the possibilities of the artificial flesh make themselves apparent in carnal ways.

The star of the show is the use of intense practical effects that may be a little too grotesque for some viewers, but is realistic in its depiction of pulsating flesh, tissue, muscle and oozing bile. The engines themselves are not a beautiful sight to behold, and their maintenance is a slimy, invasive procedure with many closeups showing the messy, meaty action. The stoical and determined performance given by de Dietrich is spot on for a scientist, head wrapped in data but their heart firmly planted in their work. This film lands somewhere in a dystopian, psychological, and science fiction mash up, making it hard to pin down a time when this is taking place or the state of society that has adapted to these humanoid engines. Audiences may find some of what Alex and her machine engage in strange or disturbing, but it all speaks to something bigger around her intelligence and her loneliness. Sexuality and shamelessness find voices in this film in unorthodox ways that make you consider lines of morality versus lands unexplored, whether you wanted to consider it or not.

While I might not have understood the draw Alex had to her engine over the company of others, I do understand an introverted creator nurturing and loving something they both built and brought to life. The engines appear to be tools to most, but where one sees only utility, Alex sees untapped potential. Ultimately, even in the face of judgement, Alex holds firm in her beliefs about her machine and how she intends to use it, regardless of what peers or administrators think. This erotic, scientific fever dream of technology beyond our comprehension is a singularly creative piece of work, brimming with originality and a boldness to display such extreme practical work and the extreme actions of people engaging with it. I can’t say if you’ll enjoy this film in a classical entertainment sense. This movie is nuanced with a sense of gravity, surprising character depth, and themes we tend to turn away from lest someone see our curious eyes observing what could be considered taboo. I can say if you choose to watch this film, it will most likely be unlike anything you have experienced before and is likely to stir curious and strange emotions in you if you choose to embrace Le Mée’s vision. [GF]