In 2001, right on the cusp of the slew of New French Extremity and ordeal horror, a peculiar, lavish period horror emerged from France. It’s many things, but above all else, Brotherhood of the Wolf (2001) is a film made during changing times, about changing times. Taking for its basis the Beast of Gévaudan panic which genuinely unfolded during the 1760s (a spate of mysterious animal attacks which prompted the time-old triumvirate of hysteria, fear and supernatural attribution), the film plays fast and loose with its range of identifiable historical elements, but uses a cast of genuine aristocratic names, as well as the verifiable fact that the king did get involved with the real case, sending dragoons to investigate the deaths. However, whilst building on elements of real history, Brotherhood of the Wolf allows its heady fantasy to run away with it; the notion of a possibly supernatural cause behind its events is certainly allowed to build, though at heart its point is a serious, worldly one, reminding us that – in the real case, as in the imagined – it is often the powerful who stand to gain from public hysteria, and they who are best-placed to exploit the already exploited. A beautiful, commanding film, its message is nonetheless as ugly as it’s recognisable.

Not that the great redress in power relations which followed hot on the heels of the Beast of Gévaudan affair is afforded so much as a lick of civility, though – and quite rightly. The film opens in late 18th Century France, at the point when the Revolution had ceded to The Terror; at this point, the revolutionary aims of liberty, equality and brotherhood had been stymied by unreason, paranoia and mass murder. Facing arrest, with a baying, cockaded mob at the door, we meet one of the film’s key players, the Marquis d’Apcher: with little time left, he sits down to write a personal testament of the events of 1764, when the notorious ‘beast’ stalked the remote Gévaudan area. As this testament becomes our embedded narrative, we see one of what we understand to have been many attacks, though there is something off-key about it: the attack on a young woman, by an as-yet unseen creature, seems vindictive rather than simply animalistic; this is a clue that this isn’t a simple wolf attack. Unsurprisingly, panic and persecution soon ensure. In this rain-lashed countryside, vengeful villagers are turning on one another, taking the generally febrile, watchful atmosphere as invitation to lash out.

However, some semblance of order arrives in the form of two riders, sent under command of the king to investigate these bloody events. Grégoire de Fronsac (Samuel Le Bihan), libertine, dilettante and gallant, and his companion Mani (Mark Dacascos), an Iroquois, bring along something of the worldly scepticism of Paris and the court, at least ostensibly: regardless, the accounts of some unnatural she-wolf stalking the land demand attention. Again, overlapping with the historical event, rumours are flying, insisting that this is no ordinary wolf. An immense hunt is subsequently called, one which draws in every aristocrat and landowner who can be called upon, but also, at points, transcends the incredibly entrenched (at least for a few more years) class system which was in place at this point in time. Unfortunately, despite this en masse effort, solutions fail, even when word comes that the deed is done, the beast is killed; Fronsac’s work is not done either, and the closer he gets to understanding what is happening around him, the greater peril he finds himself in.

The film continues less as a creature feature and more as an ornate game of politics, whereby rumours of the beast are seen to serve a purpose beholden to those already in power. The French aristocracy certainly had form when it came to backstage plotting and irrational belief: as much as the late Renaissance was in the process of ceding to the Age of Reason, stubborn and determined pockets of unreason clung steadfastly on throughout this time period, such as during the Affair of the Poisons – when key players on the court of Louis XIV decided to gamble their good graces on a frenetic period of drugging, witchcraft and murder – or, as in the film’s hallucinatory timeline – on similarly secretive cabals, poised to use terror to undermine existing bastions of power for their own ends. In the film, the beast becomes a political cipher, both to its victims and to its masters. Its masters are already powerful, of course, but secrecy, ritual and fervour will never be discounted where ‘progress’ inevitably means uncertainty, or a stripping away of power.

The role of the aristocracy in the film is key, and watching their machinations forms the largest share of the film’s running time. Even taken just on its own terms, it’s a fascinating, exasperating glimpse at a group of people clearly corrupt, self-indulgent and, yes, somewhat laughable in their little intrigues and competitions. However, we also see them in their historical role as landowners, guardians and, to a certain extent, the face of the ‘greater good’ in French society – though that may depend on who you asked. It’s also worth saying that these were the only people with the time, means and inclination to ponder events such as those in Gévaudan: everyone else, regardless of their fears, had to live, farm and work the land regardless. Even the grand hunt, the first response to the beast, feels like an extension of a noble pastime – hunting for fun, as we see in the repellent scene of the pile of dead wolves, so substantial that it obscures all else behind it (as much as it’s a lot easier to find this scene repellent when not at risk of being killed by wolves: French folklore was there to remind 18th Century France of what had allegedly happened in 15th Century France, but then even in the 18th Century, wolf attacks were a regular occurrence.)

We also see in the film that, in this period, all roads lead to Paris: the goings-on of Versailles loom large over the nobility, often crowding out all other concerns. One criticism of the film has been that it lingers too long over the intra-familial politics of these characters, hanging out in its (rather splendid) Rococo dining rooms, palaces and brothels at the expense of the horror or dramatic elements – though even its horror scenes are a bit Rococo, oddly ornate and detailed, if dreamlike. From this writer’s point of view, the time we spend with this effete bunch all adds to the immersive, heady ambience of the film, placing us amongst their number to ponder their schemes and outrages. Their social gatherings are faintly ridiculous, sure, but they matter to our key players, and even though our heroes Fronsac and Mari are often banished to the periphery of all of this, they’re still ordained by it, and still must navigate it. Feminine intrigue plays a key role here, too, both aristocratic and otherwise, with the impossibly beautiful Monica Bellucci doing a star turn as a fallen woman exercising immense, if covert power: another French historical tradition, present and correct.

Mari’s presence in the film also reminds us that this was a modernising France, flexing its muscles as an imperial power; talk of a New France – from where Mari comes – refers to France’s race for new territories and opportunities. Mari brings his culture and beliefs with him, overlaying another supernatural element onto the film’s more worldly ones, though ultimately pressing home the fact that we cannot underestimate the impact of race and empire on events in the film. New prospects bring new anxieties. Perhaps there’s a certain amount of stereotyping of Mari as the sage medicine man, but he is nonetheless a valued friend to Fronsac, if a source of baffled pantomime amusement for many of his aristocratic peers, fascinated by his talk of totem animals but dismissive of him as an equal.

The film is not just a character study of the aristocracy, though, and nor is it in any way a straightforward creature feature, not least because it hangs onto its reveal of what, or if this creature is. It’s also, unexpectedly, a martial arts film in places too, with simply loads of time given over to choreographed, often slow-mo fight scenes. It ain’t kung fu, but this is still martial arts in a wider sense, and frankly, it looks for all the world like kung fu, whatever the costumes. Mari is the chief proponent of this, seeing off the traditionally hard-to-believe number of assailants, but lots of the film’s more high-action scenes depend on improbable manoeuvres and physical abilities, too.

This is a film which lurches from languid and picturesque to sudden motion, tension and violence. As such, it blends elements from a range of different genres, and it does it in ways which don’t necessarily work on paper: martial arts, historical drama, momentary grisly violence, character study and horror may seem like a hard sell, when all bound up in one place. And yet, the film’s odd elements work, despite jarring sharply against one another from time to time. Sure, Brotherhood of the Wolf can be camp, or too loose and self-indulgent in places, but it’s a terrifically engaging historical romp which looks and sounds wonderful, with each shot set up like a piece of art. It’s hard not to be carried away in its wake; it seems to have been made to be a guilty pleasure. It tries hard to balance its horror elements – unforgiving, pre-Romantic landscapes, petrified damsels, mysterious creatures, blood and menace – against its bedrock of historical veracity, all interestingly selected, shot and acted.

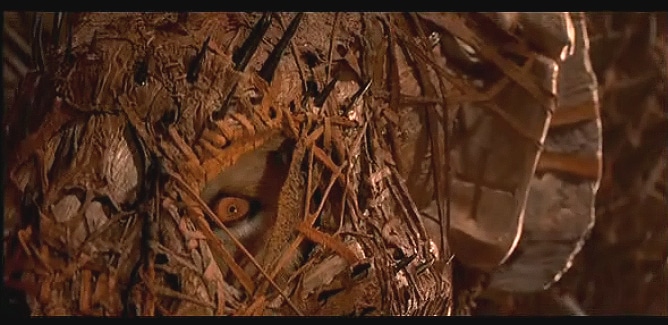

It is perhaps most interesting, though, for its choice of source material. The historical Beast of Gévaudan case, being such a shocking and to an extent an inexplicable-seeming event, inevitably drew down claims of a supernatural force at work – something otherworldly, operating beyond the abilities of even a large or particularly ferocious wolf. Even a determination to regard these attacks as the work of one creature shows the beginnings of a mythologising tendency, this being often one step away from an outright supernatural belief. As such, events at Gévaudan have steadily become enmeshed with werewolf folklore – largely through being grouped in with other, adjacent beliefs in werewolves which had little to do with Gévaudan itself, but the misapprehension was there. Brotherhood of the Wolf, similarly, is often assumed to be a werewolf film: it looks as though it’s going to be, it sounds potentially like it could be, and on first glance, there appear to be supernatural elements at work. It even plays momentarily with some of the werewolf folklore which has been created by cinema, for cinema: the discovery of a metal fang, for instance, suggests that this is no ordinary wolf, and in horror cinema, when it’s no ordinary wolf, it’s likely to be a – well, you know what.

But, although the film allows itself a few ritual gatherings, some ritual killings and a mysterious, bloodthirsty fraternity, this fantastical add-on does not take away from the fact that this is no werewolf film after all; this revelation is for us, as well as the key characters. The creature has earthly origins, and it is controlled by a human. The film has its fantasies, and it has its lavish, supernatural plot points, but ultimately it’s earthly powers which are attempting to hold sway here – the same as ever. Abnormal wolves, mysterious creatures, even werewolves themselves: where these allegedly crop up in history, it is often as a result of a particularly traumatic event or particularly straitened times, as in Gévaudan. Ultimately, though, the explicable – the just-about explicable – is traumatic enough. Brotherhood of the Wolf manages to marry its luxurious fantasies to its realities, and it does so without sacrificing its vision of a peculiarly anxious moment in history, one where the spectres of war and rebellion were there to worry away at the edges of polite, restrained society, by then poised and peering into an abyss of change and progress.

Brotherhood of the Wolf is about to get a 4K UHD remastered re-release, courtesy of Studiocanal. It will be released on May 5th, 2023. For further details, please click here.