Please note: this review discusses some points re: the film’s structure which could potentially offer mild spoilers.

The Unheard (2023) feels like a difficult film to review as one, cogent whole. It doesn’t demarcate a number of chapters with title cards, like an awful lot of films do, but feels very much like two, distinct, different films running one after the other. This means a careful, clever premise given plenty of time and space to develop – which is then pitched against a frustrating array of tropes and pitfalls. It’s meticulous, then it’s cursory. What a tantalising, frustrating experience from the Rasmussens, who do some painstaking work here, only to set it bafflingly aside.

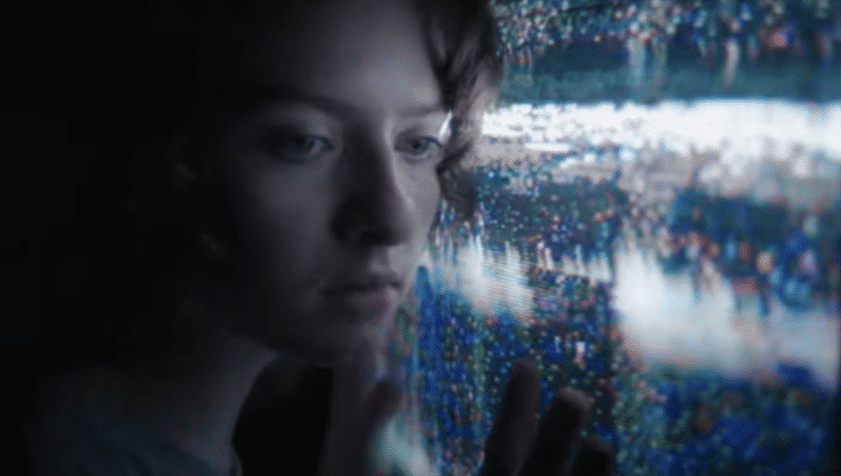

The film opens with some flashes of the past (via VHS cassettes, of course) which almost immediately sink into… silence. Our protagonist Chloe (the talented Lachlan Watson) lost her hearing as a child after having meningitis. When we meet her, aged twenty, she is about to take part in an experimental treatment to potentially undo this damage. We get a sense of how this feels for her via some painstaking audio work in the film; it isn’t quite silence which she’s experiencing, actually, more a kind of all-encompassing, baseline hum which locks out the frequencies of speech (The Unheard surely takes some cues from Sound of Metal (2019), which also features the perspective of a young person who loses their hearing). Having established something of what life is like for Chloe, the film reverts to more conventional audio; we revert to a hearing person’s perspective, now listening in to the conversations she has – with the help of apps on her smartphone – with her new doctor, though the film moves in and out of Chloe’s experience at certain points. But, tellingly, she explains to Dr Lynch (Shunori Ramanathan) that, despite her hearing loss, she has always felt like part of the hearing world; this revolutionary new stem cell treatment would, for her, give her back something which she has never felt was totally lost.

The first treatment goes well. Afterwards, she heads to the old family home, both to recuperate and to prepare it, finally, for sale. She texts her father – only her father – to update him on how things have gone; it’s clearly signposted for us that Chloe’s mother is not around, particularly when she begins mingling with the locals for the first time since her illness and relocation. They readily address the past: Chloe’s mother disappeared, and the family left the area as a result. There is an unpleasant sense of absence at the heart of this film.

More trips into the past ensue as Chloe comes to terms with all of this; part of this process involves the expected scenes where she scans through old photos and family videos. But, up until around the hour point, this is a seriously promising story, even if some of its elements are tried and tested. The film offers up carefully-curated loneliness in the character of Chloe, a thoughtful young woman dealing with the double blow of not-quite-bereavement, a horrible partial state of being where her mother is not there but not gone either – and the devastating aftermath of a life-threatening illness, which has taken her hearing, and isolated her still further.

It’s worth pointing out, by the by, that there’s no intimation in this film of a Deaf community which Chloe has embraced, or which has embraced her; here, hearing loss is a decided negative, and always treated as such. The film reminds us of how this might feel at key points, and the sound design here is really excellent. It’s not just the absence of sound which is difficult to bear; the (auditory) flashbacks which occur are equally unpleasant, because they are intrusive and unexpected. In effect, everything is unsettling; when Chloe places a huge knife on her bedside table, in the old family house where she feels and seems incredibly vulnerable, we can applaud her good sense. After all, aside from everything else, there’s a low-level sense that things are somehow ‘off’ in this place; the people, the memories. They’re uneasy en masse, but subtly so.

And then we get to the hour-or-so mark, and things begin to falter. One film ends; another, less successful film rolls.

Firstly, at this point, we get a significant lag: it’s a lag in pace and it’s a dip in plot cohesion (with one utterly nonsensical plot point which could potentially jar the audience out of their satisfying suspension of disbelief, even before the other issues emerge). This could potentially raise an eyebrow, but no sooner have you made your peace with this, than the film elects to pick up a couple of big old red flags, and waves them enthusiastically. The film slows, it stops, then it picks up again, only with a much more familiar-feeling direction.

Oh, no. Suddenly, this is no longer a sensitive blend of supernatural and worldly horror, with Chloe left to decipher the strange sounds and voices she begins to hear (as much as VHS video is overused in modern horror, here it at least forms part of the storyline in some believable way). That gets swept aside, and suddenly, it’s just another puzzle box to solve, with a resolution most viewers will guess as soon as that red flag flutters. The film even does the unbelievable, and more or less parks Chloe’s hearing issues, transforming her from a young woman with a carefully-observed trait into a much more recognisable, and as such more anonymous character. Soon it transpires that it’s turning into another film where that happens to a her.

From here until the two hour mark – too long, too open to misfires – the whole film feels much more anonymous, which is a real shame: The Unheard has good production values, looks great, and offers some strong performances, but its eventual resolutions do little to balance the film’s early promise. It even invites some exasperated yelling before the end credits appear. How can this be the same film? It does so much good work, which it then spends an hour taking away again, piecemeal. As such it’s not without merit – far from it – but the resounding feeling by the end credits is frustration.

The Unheard (2023) will be available on Shudder from 31st March 2023.