The Hellraiser franchise is the thing that won’t die. Decades after its inception in the 80s, and since one excellent sequel in the form of Hellbound (1988), it has morphed and been sold on and changed and spoiled and (partly) redeemed down through the subsequent years. The original story’s Cenobites have walked the city streets, orbited the planet, even rocked up rather awkwardly to offer a rather banal plot explanation, hither and yon. But Hellraiser fans are loyal, and the speed with which they have historically thrown in their lot with the likes of Hellraiser: Inferno (2000) and Hellraiser: Deader (2005) speaks to their resilience as much as their passion. Even when you hate where it goes and what it does, you find yourself lining up to see it. Completely appropriately, the Cenobites inspire their own jaded brand of faith.

Rumours of a full ‘reimagining’ have been drifting around for years, though in more recent years we haven’t got much further than Hellraiser: Judgment (2018), as notable for swapping Doug Bradley for Paul T. Taylor in the role of Pinhead as for its own plot path. As for a true remake, or a ‘reconfiguration’, as Clive Barker referred to it? Rumours of directors have been attached to a potential project for years – Bustillo and Maury, Laughier – but nothing has ever come to fruition. So when Hulu, via Disney+ of all things, began mooting a new film, the general response was of muted excitement with some justifiable background levels of cynicism. The trailer was late to appear, given the looming release date – which caused some commentators to doubt it was coming at all – and then there were some murmurings regarding the casting of actress Jamie Clayton as Pinhead (I keep the gendered noun ‘actress’ here quite deliberately, as it was Clayton’s gender which contributed much to these murmurings). But then – bam – it was out, it was real and it was…not too bad at all, actually, albeit with a few key reservations.

The following feature is less a conventional review and more of a set of reactions to key elements in Hellraiser (2022) – as suggested above, the good and the bad – as felt by a lifelong Hellraiser fan who, yes, has sat through every single sequel, occasionally boring my co-viewers with unrequested comparisons to the novella, observations about Easter eggs and a general ruckus of heartfelt opinions. As such, the following article contains spoilers, so please don’t delve until you’ve actually seen the new film (which, by the way, I’d misread as being a TV series on first encounter, and can’t help but think that this would have been a great way to dole out the scares and the plot reveals in a more digestible format: a different approach to slow-burn tension, character development and general satiety. But enough about that thing which turns out not to exist; we have an actual film to discuss.)

The Good: Euclidean Architecture

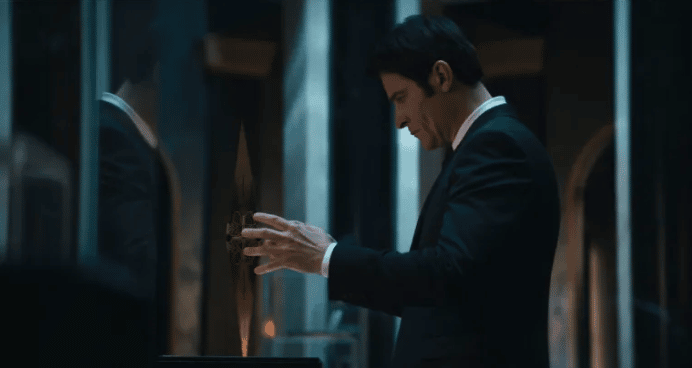

The film wastes no time establishing that a key player here is jaded rich collector Voigt (Goran Visnjic), whose obsession with the…well, what we’d have known until now as the Lament Configuration box (more anon) has induced him to devote his entire home to the structure. This echoes initial ideas – and some, limited exploration – of the possibilities of the box as a blueprint for a building or buildings; previous films have hinted this, though it has not turned out to be integral to their stories (as you’d perhaps expect it to be). There were also some ideas about forging a link between the Cenobites and a bordello; these did not reach the point of filming, though the imaginative possibilities are quite something.

But back to the present: occultist Voigt understands a significant amount about the Cenobites and what they can offer; he has refigured his expansive home along these lines, with the aim of controlling and subduing them to his will. Bold. God grant us the singlemindedness of a rich, white man; one tried to solve war in Europe with a Twitter poll this week. Whilst comparisons to the Thirteen Ghosts (2011) remake come thick and fast here, there’s no denying that the aesthetics of this place are strikingly effective: the shifting panes of glass, the cages rattling down on polished marble, the overall use of space and lineation. This recurs elsewhere in the film though, so it isn’t simply down to Voigt’s money and (limited) abilities to control his fate. Straight lines and forced perspectives pop up throughout; even the kids’ playground where poor dupe Riley passes out early in the film turns into an intermeshed array of lines and angles. This might suggest that hidden agencies of order are at play in a disparate and alienated modern world or, you know, it might just look really, really good on camera, but the background design work in the film is a treat: it recalls aspects of Hellraiser (1987) but expands them, filling the screen, dragging angles and lines into impossible points in the distance and disrupting everything with geometric shapes filled with absolute black, with absolutely no light within. Beautiful.

Of course, this geometric obsession transfers onto the flesh, too – both of the Cenobites, and of those unfortunate enough to encounter them.

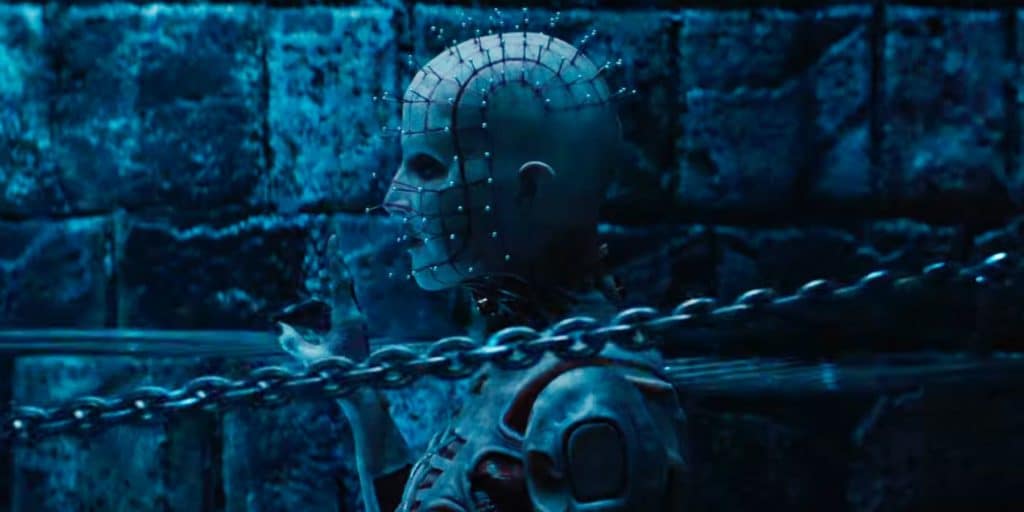

The Good (-ish) – 21st Century Cenobites

Speaking purely in terms of appearances here, this new array of Cenobites are good – or in parts, at least, they’re good. We have finally reached a point now, after riding out more than a few wilderness years – where CGI seemed to actively hinder illusion rather than permit it – where computer graphics genuinely augment certain scenes, blending more or less flawlessly with practical FX. These new Cenobites are rather dapper, by extension. Their pins and scars glitter with pearl and precious stones. Their heavy drapery has been replaced by quite scanty garments; you could go for a light walk in these (which they do, kinda). All in all, these Cenobites probably shop on Etsy.

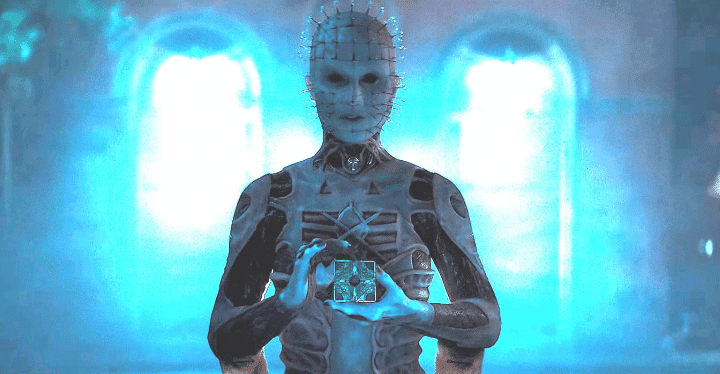

As for Clayton as Pinhead, she is a real highlight of the film (any concerns that, being a woman, she was going to speak her lines with an overtly feminine pitch turn out to be ill-founded: she does not). Hers is the only Cenobite role which has some soul, however. Perhaps this is to be expected, as Pinhead has always been regarded as the de facto spokesperson for the Order, and Clayton gets to deliver some of the film’s most memorable, even poignant lines by the end. She looks marvellous, too: director David Bruckner has understood the old lesson that less is more, not allowing us more than a peek until the film is around an hour in, so she comes as a real surprise – familiar enough, but new enough to pique interest. It’s also nice that the original Pinhead, Doug Bradley – who has on occasion said that he feels strangely protective of the character – sent Clayton his wholehearted support.

So far, so good. But in amongst all of these aesthetically-pleasing decisions and carefully-controlled reveals, sadly the rest of the Cenobite gang are rather forgettable. Yes, they’re dressed to the nines, but there is little sense of them as characters, or even as formidable entities at all. They just pop up on the periphery, walk around slowly and get quickly, threat-disparagingly outpaced; there are more of them than there are in the 1987 film, which is fine, but as such, they desperately need to feel more momentous when they are there. Another issue, for me, is that they seem to all act quite autonomously; there’s little sense that the Cenobites are an Order, working together. In the 1987 film, one key strength was in how it felt like The Gang’s All Here when all four of the Cenobites were in shot. But even separately, they felt more to me like they were operating as part of a cohesive group – which was somehow more frightening. They had both vivid personal characteristics, and shared goals. That is significantly eroded in the 2022 retelling. Their flayed flesh is oddly bloodless, too (albeit said from the perspective of someone who has absolutely no idea how bloody flayed flesh actually is). The first Cenobites looked mortifyingly injured, dank and dark; the new Cenobites have clean, clear bones and neat wounds all visible. They have been cleaned up. Who’s cleaned them up? Surely a formidable bunch in their own right.

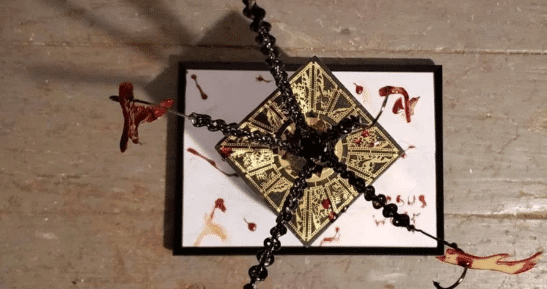

The Good: New Configurations

One of the most successful changes in the film comes in the form of the new, remodelled puzzle box, a new spin on that key to a new dimension with its own horrific codes and rules. It was always a fearsome proposition, honestly – a true testament to Clive Barker’s skills as an imaginative writer, and also to what he achieved on a limited budget with essentially no filmmaking experience in 1987. The Lament Configuration box took on a life of its own in films thereafter, but it retained one essential quality: namely, that by solving the puzzle, the Cenobites would be summoned. That was it. Beauty is truth, truth beauty; that is all ye know on Earth, and all ye need to know. The box itself didn’t have too many different modes though. By finding the right combination of pressure points on its surface, it could be made to shift into a couple of different shapes, opening a door in the process. Similarly, by doing the same thing again, it could send the Cenobites back. Horribly simple.

Skip to 2022, and the lore of the Lament Configuration has been overhauled: this adds a genuinely interesting and creative layer to this storyline. The box, by the by, looks fantastic: there’s a real sense of its having carved elements, more possible modes to contend with and more potential for direct threat (now that it operates as a malign presence in its own right, rather than an inert puzzle box which really needs human interaction in order to do anything at all). It switches through an array of different shapes now, and more than that, its configurations each have their own associated mythology. The configurations are intricately linked to the fates of those who get to grips with them, who unlock them.

Voigt knew this much, and had focused his research on them, running through the usual horror trope of recording his findings in sinister monochrome in a sequence of bound notebooks (no one ever writes this shit down on dayglo Post-Its). This information is eventually gleaned by the film’s key protagonist, Riley (Odessa A’Zion) when she tracks down Voigt and his legacy, though hers is a hard-won series of lessons, fractured and confusing at first. The practical lessons are more memorable, but cost her far more: nonetheless, she finally avails herself of configuration lore, understanding enough to play the Cenobites at their own game, come the end: she can’t simply solve the box again, however. Her bargain with them strikes a balance between learning and self-sacrifice. It is only via this that we even hear the phrase ‘lament configuration’; it’s only one of the potential outcomes. This is a rich and clever idea which builds purposefully on the pre-existing mythos, doing something meaningful with it. The puzzle box is a character in its own right now.

The Bad: chance, rather than choice?

That all being said, it’s as an offshoot of the whole new configuration idea that the film, for me, stumbles badly. That the puzzle box has new potential tricks, sequences and powers is fine; this allows for some truly expansive elements, with some engaging scenes. However, the fact that it operates as if it has aspects of sentience – that creates some issues.

The overarching idea behind encountering the Cenobites has always placed the character flaw with the human who is stupid, or bold enough (depending on your outlook) to mess about with the puzzle box. Some of those did so because they were jaded decadents seeking the next sensory adventure; Frank Cotton may not have known exactly what he was letting himself in for, but he knew something, and he tried to solve the box anyway. Kirsty, Tiffany – their cases were more tragic, but the uniting factor was that they did try to solve the box, and this was enough, at least at first. Kirsty only initially avoids being torn to pieces because she has can bargain with a strange and glaring omission on the Cenobites’ part – the fact that Frank escaped them. Others are not so lucky. A whole wardful of unwitting guinea pigs are given boxes to solve in Hellbound; by definition, these people haven’t given their consent because there’s no way they usefully could. But we only ever get hints that the box is somehow in on all of this. Like your standard Devil’s bargain, it requires people to make the first move.

Not so the new puzzle box, which has some qualities in common with the device in Cronos (1993), right down to the eccentric millionaire who eventually tells its story. It’s far more overtly involved in Cenobitic machinations here. Essentially, the new puzzle box can send out a blade and ‘mark’ someone by drawing their blood; somewhat like a zombie bite, something akin to a pyramid scheme, the only way to escape the subsequent appointment with the Cenobites is to procure a number of other victims at their behest. Quantity over quality? Maybe, but the whole idea of the box catching people by injuring them feels so different to the old mythos that it simply doesn’t work that well. It all feels a bit It Follows, only it’s the Cenobites who are following, even though they’ve never really needed to drum up numbers, because the whole point is that people are fallible enough to offer themselves up to them.

That whole initial set-up (which worked a charm, by the by) where pretty boy Trevor (Drew Starkey) tricks Riley into nabbing the still-mysterious unclaimed artefact: wouldn’t that have worked just as well, on many levels, by luring her in on its own terms as a mystery object, especially given her own relative poverty, and addiction issues which could at the very least have clouded her objectivity? The whole addiction motif is otherwise an odd thing to centre, as its only other purpose seems to give us a reason to believe Riley’s brother wants to look out for her (which of course he could have done anyway) and to drum up one scene where she has a minor relapse, although we all know that the Cenobites don’t particularly require people to be in altered states beforehand; it’s kind of their job to alter states. Sure, there has been an element of Lament Configuration as bait in the past, but never quite like this; a number of the main protagonists in the 2022 story get picked off largely as a result of a moment’s bad luck. Mercenary, sure, but less well-rounded, the richly-layered world of the Configurations could have come to fruition in this film by means other than pure chance.

Another unwelcome aspect of the new film which also relates to how the horror has always been centred on human error: the Cenobites are liars now. They never lied in the original film. They never lied in the sequel. There were rules. Even in Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (1992), a film which has long divided fans of the franchise, Pinhead’s deal with poor, desperate Terri is on own terms, legitimate: she gets what he promised. She can dream. What he requires in exchange is service; job done. Move forward thirty years, and the Cenobites are far less averse to telling fibs to get what they want, which seems to be – victims. More victims. The selection process has been dramatically opened up, and the recruitment process has been relaxed accordingly.

Perhaps this goes hand in hand with this new world order, where they ensnare the unwitting through the sudden spasmodic movements of the puzzle box. But it feels off; it may be more in keeping with a more Biblical take on demons and bargains, you could say, though this is a big shift away from the more recognisable mythos which many of us love. It also leads to rather a lot of muddying where the plot is concerned: the Cenobites’ motivations are less acute, the level of threat which they can drum up is less consistent, and it takes a lot of rather jagged plot reveals in the final act to come to a meaningful conclusion (which it does, however, muster).

Conclusions

At least some of these issues, I’d argue, come from ambitious, but at times inconsistent changes to the story’s fundamentals. Funnily enough, whilst they have cleaned up the overall look of this film – clean, delicate, often light – they’ve balanced it out with a few markedly opaque, even murky plot sequences. Perhaps the Hellraiser series still has a quota of murk to fulfil. On balance, I’d rather it was aesthetic, but on the whole, I did quite enjoy Hellraiser (2022). Sure, it’s not perfect, but it has a decent array of imaginative developments and ambition, and the fact that it exists before us is in itself a blessing, given its long lifespan as little more than a rumour. Will it recruit a new generation of fans, given its Disney+ streaming release? Perhaps, perhaps not, but let us hope at least that it will come as an almighty shock to a few people clicking ‘play’ on this unknown quantity. For the rest of us, it’s a largely welcome addition to a beloved mythos which, because of our fondness for it, makes us very discretionary. It’s a brave team that even takes this on but – overall, I’m glad they did.