Rounding off our Fantasia 2022 coverage, we have a glance at another run of short films – this time, directed exclusively by women. And it’s a varied, often very dark collection of films, touching upon subjects such as superstition, statelessness, secret worlds, the afterlife, friendship, love and trauma.

Lily’s Mirror operates in a ghastly early 90s analogue world where men not only dominate the world, but seem to cut, hack and murder their way through it too. On a dinner date, Lily (Linnea Frye) gets her hand chopped off by her partner; the really scary thing here is, no one seems to particularly mind. It’s just a quirk; all guys do it at least once, it seems. In dealing with the aftermath of this, Lily undergoes a kind of dark night of the soul, fearful of people (understandable!) and getting odd, phantom pains in her missing hand. A sympathetic doctor introduces her to a mirror box; by looking at the reflection of her remaining hand, she can train her brain to recognise that the other hand is not actually there. Well, it turns out that the mirror box can do more than that. There’s a great idea at heart here, and a sharp, satirical edge to it too: a peculiar fantasy, sure, but one which uses fantasy to question the world we do in fact find ourselves in.

Everybody Goes To The Hospital is the only 100% animated film in the collection, but despite the presence of this, and a child narrator, the film is in fact a very bleak exploration of childhood trauma; it’s just done using the language, form and symbolism that children would recognise, and it’s based on a real childhood experience. Little Mata is ill; after a week of ‘flu’, her parents realise that she’s suffering from something far worse, and so they take her in to hospital to get examined. It turns out that she needs an operation, and the situation escalates even further once she’s under surgical care; the film really illustrates the helpless, frightening aspects of being a small child, especially where it emphasises the vast chasm between adults and children. It’s a thought-provoking, and rather sad story which I hope was cathartic in some way.

Wild Card is named for the dating agency which features in the story, but it’s a wild card in its own right too: it eschews a neat narrative arc and leaves the audience wondering what happens after the credits roll. We meet Daniel, a man looking to meet a special someone via what used to pass as Tinder back in the 80s – namely, a video dating agency, where you record a message and the cassettes get sent out to prospective partners. And, by the way, analogue technology is everywhere in this film collection; tech nostalgia is a kind of rite of passage in a lot of independent film now. Anyway, Daniel gets lucky, getting picked out by a kind of earthy femme fatale by the name of Toni; sometimes she’s enticing and mysterious, and sometimes a little spit-and-sawdust. But Dan is intrigued enough to follow her – somewhere…

Similarly, Punch Drunk is a snapshot rather than a fully-formed story, but what it does provide is a glimpse into the everyday details of life for a woman where sex and gender intersect in often unpleasant, attention-draining and even traumatic ways. Nora is a sparky, no-nonsense character working at a bar; she has to grit her teeth and get through her shift, despite some time-of-the-month-plus issues which are bothering her; it’s no fun trying to interact with the world whilst bleeding through your clothes. But whatever nerves she feels about an upcoming gynae procedure – which she discusses quite openly with her colleague and partner at the bar – it seems that the bar itself harbours some unpleasant memories; the whole film just proves that you can’t always get away from sources of anxiety and discomfort in life. What we get here is a likeable character living through some inescapable and unsettling experiences, where the subject matter is handled unflinchingly, but carefully.

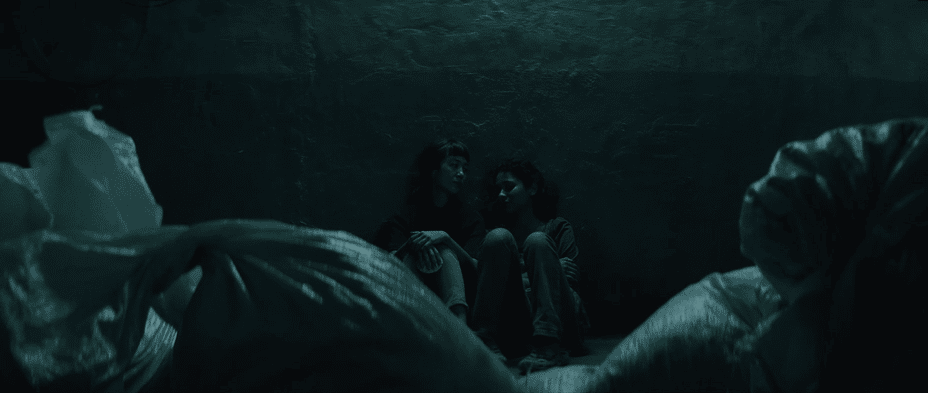

Stained Skin is a very artistic concept, a blend of very beautiful animated sequences and contrastingly, a tough, unforgiving real-world environment; these two worlds collide via the art of storytelling. In a grim commercial laundry, a woman tells stories to her friend – as a means of escapism for them, at first. She tells her all about a girl called Nanami, who was taken to the bottom of the sea and put to work gathering pearls; however, although this is a fantastical world, it seems that many of the story’s elements overlap with the women’s reality: there is forced labour, imprisonment, escape, wealth, class and crisis. Eventually, when the story seems to run out without an ending, the other woman picks it up, and it becomes a symbol of hope and rebellion, a source of comfort. This is a visually very strong film with beautiful music which successfully conveys a sense of two separate but linked worlds.

The Anteroom is a Spanish language film so I confess, I will have missed the finer points of the dialogue with my extended Spanish vocabulary of about ten nouns, but here’s what is clear: it is a low-key sci-fi film where a woman and baby seek refuge at a mysterious sanctuary. Gaining access to it is a challenge, and certain conditions must be met; a disembodied voice assesses the woman’s suitability, aware that she is the last survivor of a group. But carrying a baby into this room is, we gather, considered a significant negative. To get to safety means a set of risky tasks where nothing is certain. This is a dark, ominous film, one of that new gamut of science fiction visions where the sci-fi itself is rather minimalist, but no less effective and ominous for that. Again, there are no comforting certainties at close of play.

In Daughters of Witches, an exhausted new mother, Clara, has just travelled from her home in the US back to Mexico at the behest of her family. Apparently, it is customary for new baby girls to undergo a particular ritual, and this is the familial and cultural expectation, although Clara – who has been away from this world for some time – is worried about it, as it means leaving her baby daughter out in the woods. Despite the assurances of her close family, she is scared. The reason for all of this is, however, sacred: the first animal to approach the child at dawn will represent the child’s spirit animal, and protector for life. Charming? Or eerie? The interplay of multiple anxieties takes hold of the film as the ritual unfolds in ways which feel wrong, somehow: could it all be down to the absence of the family matriarch, who passed away without meeting baby Iris? The performances here are excellent, and the photography of the rituals by night are very evocative, with a perfectly ambiguous ending.

Don’t Go Where I Can’t Find You is a very diffuse, mood-infused piece of film which interrogates ideas about grieving, love and loss. When her partner Freya dies unexpectedly, composer Margaret attempts to channel both her own sadness and Freya’s protestations that there was something supernatural going on in the house; before her death, she claimed that the spirits of the house were coming for them. Margaret believes that through her music, she can hear Freya; revelations of guilt begin to filter through this grand new musical project, for reasons which are slowly revealed. There are some nods to The Yellow Wallpaper here, as well as some evocative use of ideas around EVP and spirit recordings; music is, of course, integral and its role as elegy and invocation sounds very much fit for purpose. Aesthetically and aurally beautiful, the film stands as a evocation of grief.

Finally, Kin takes us back to 19th Century America and a homestead in the middle of nowhere, where sisters Ida and Annabelle have ‘put down shallow roots’, as the older girl describes it later in the film. They are looking after their infant brother John; clearly their parents are deceased or otherwise absent, and Ida handles the family dynamic in a very terse, strained way, laying claim to a particular responsibility. We soon appreciate why; she seems to be haunted by something, though whether that is all in her head or otherwise remains to be seen. The film starts with straightforward deprivation and desperation but moves somewhere else entirely, to a place where family ties are tested in unexpected ways. Kin tantalises at a back story which could easily form the basis of a feature, but it works well in a short film format because just enough is done to actualise the threat to the family. Reminiscent of It Follows in some respects, this is an effective and understated story with a genuinely effective hook.