There’s been a tendency in pop culture to present serial killers as monolithic: they’ve often been painted as almost supernatural, not only ungoverned by the usual social and cultural norms but devoid of familial ties, too. But that is changing: more recent films and TV have hinted at least at something more going on with these characters, sometimes showing them capable of (very select) care and affection. Megalomaniac (2022) hovers in the space between both of these approaches – the old and the new. It deals in extremes of nastiness and cruelty, but it also offers a different perspective, one where the sins of the serial-killer father are visited upon children, and how this legacy impacts upon them in adulthood. The resulting film ain’t pretty, so be warned.

The film starts from the point of a real-life Belgian criminal case, the unsolved ‘Butcher of Mons’ murders of the late Nineties during which several women’s bodies were found dismembered. Before police could locate their killer, the case went cold, suggesting that the culprit had either died, or been caught for something separate (people with this much of a fixation on vulnerable women rarely ‘just stop’ because they change their minds). Megalomaniac starts with a hefty and unpalatable ‘what if?’, imagining that the Butcher of Mons had other victims and had children: the film starts with a bloodied woman giving birth, the man at her side immediately handing the baby to another child, a little boy. There’s no tenderness or happiness here, just a kind of horrible acceptance that there’s another member of the family.

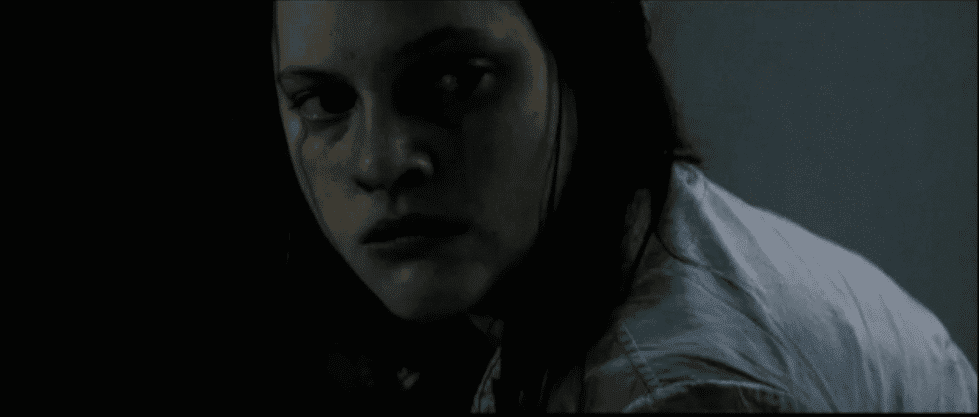

We are invited to infer that this little boy – Felix – is the same person we then follow into adulthood, where it seems he has picked up where dear old dad left off: he captures and kills women himself now, as visions of the older man seem to steer him along – or at least accompany him. The baby has grown up to be Martha (Eline Schumacher), who is attempting a different route through her life: she has a low-status but respectable job (as a cleaner at a small factory) and regularly engages with a visiting social worker, who has clearly been enlisted to keep an eye on this withdrawn and troubled young woman. But what comes across as mute acceptance in the workplace gives way to a raging, angry kind of loneliness when she’s alone at home, in the to-be-expected shambles of a house she shares with Felix. Felix (Benjamin Ramon) seems to care for her and he looks out for her, to some extent. She conceals the worst from him, largely obeys his edicts and tries to do what he wants – that is, appear normal, raise no cause for alarm. (It’s a bit rich, coming from him.)

Martha’s attempts to live normally were probably always doomed, but her treatment at the factory – where she is routinely mocked, attacked and raped by one of the workers – makes her more desperate to cling onto something normal, or what looks normal through her distorted view. The next meeting with the social worker – which falters and gives way to mocking, sexualised language – nearly blows Martha’s cover altogether. But ultimately, the people in a position to help her do so little, that her jagged behaviour is understandable – at least to an extent. Things are growing more difficult: her brother’s murders are beginning to frighten the people of Belgium who fear that the Butcher of Mons has made a comeback. Perhaps sensing the change, Felix makes a grand, sordid gesture and offers to share one of his victims with her, another occasion where Martha’s tenuous grasp on reality shines through; she is pleased. However, the real issue here is what happens when the ‘family’ once again expands, as the past harms suffered by these siblings draws other people inescapably into their orbit.

Megalomaniac makes it feel as though the New French Extremity (albeit counting in Belgium here) never went away; it just paused, regrouped, and came back more brutal and unpleasant than before. The film looks that part, too: everything is dismal, blue-hued and devoid of any warmth; even the dream sequences are nearly fully in charcoal tones. It could also be criticised along some of the same lines as the most striking New French Extremity titles were: namely, in its treatment of women. It is genuinely horrific throughout, with unflinching shots lingering on nameless, blameless women being hammered, stabbed and tortured; we are privy to this via Felix, who relives these moments again and again. It could hardly be less comfortable to watch. Of course, the savageness is the point and the film is intended as a character study of a dreadful, damaged man operating on the outskirts of a deeply misogynistic world (of which Martha, too, is a victim). There are people like him out there. However, he remains an enigmatic man in black, a person whose horrific past has still been turned to his will; he controls the world he finds, he is the master of the house, he is Martha’s custodian. He will ‘look after her’. This won’t endear him to many viewers, but nor should it.

Similarly, people waiting for the big, redemptive, expected arc where someone like Martha begins shooting and hacking her way to Final Girl supremacy may be disappointed; the film does not consider it owes us that, and maybe feels that kind of disingenuous plot motif being so often added obliterates a lot of disturbing truths about men and women at their lowest. The plot instead follows her to a more complex, ignominious place altogether; what befalls her tests her through her limited emotional vocabulary, for she is a young woman who lacks the means to escape her fate. It’s a study in suffering, where female redemption is hamstrung by other factors; you may choose to see that as symbolic of a wider truth, broader patterns. A film which contains no points of light, Megalomaniac is a queasy, unsettling watch. Its ugliness is so complete that you feel defeated by the end, but then what redemption could, would or should make all of this ugliness palatable? If this lesson was always the point – then bravo.

Megalomaniac screened as part of the Fantasia Film Festival 2022 on 22nd and 24th July.