So, DUNE is finally out, the reviews are in, and the consensus is that critical darling Denis Villeneuve has pulled it off against all the odds. He has presented an adaptation of the once-termed ‘unfilmable’ 1965 novel Dune that has – incredibly – managed to please the full spectrum of viewers – the hard-to-please book fans, the mainstream audience entirely new to the story and the majority of film critics; it’s made enough of a splash at the box office and on HBO’s streaming service to have part two greenlit. It’s an adaptation that steers carefully between the poles of the kind of philosophical, dreamy arthouse flair that Frank Herbert’s intrigue-riddled far-futurescape seemingly demands, and the kind of adventure film that presents the possibly most achingly mainstream thing possible right now – the physical presence of the hugely easy-on-the-eye Jason Momoa swaggering and swashbuckling his way through some terrific, blood-soaked action sequences as Atreides man-at-arms Duncan Idaho.

I fall firmly into the ‘book fan’ camp, as well as, as I’ve presented in excruciating detail before on this site, being a fan of the much-maligned 1984 David Lynch box office failure. So, it was almost impossible to view Villeneuve’s much-awaited work for the first time without both the original text and the Lynch version bubbling up in the mind’s eye in comparison. What was very soon apparent is how carefully and clearly Villeneuve’s script teases out and faithfully delineates the main themes and plotlines of the text – something that Lynch’s otherwise fascinatingly fevered work dropped the ball on at important junctures – and how certain aesthetic and structural choices contribute toward its mainstream accessibility.

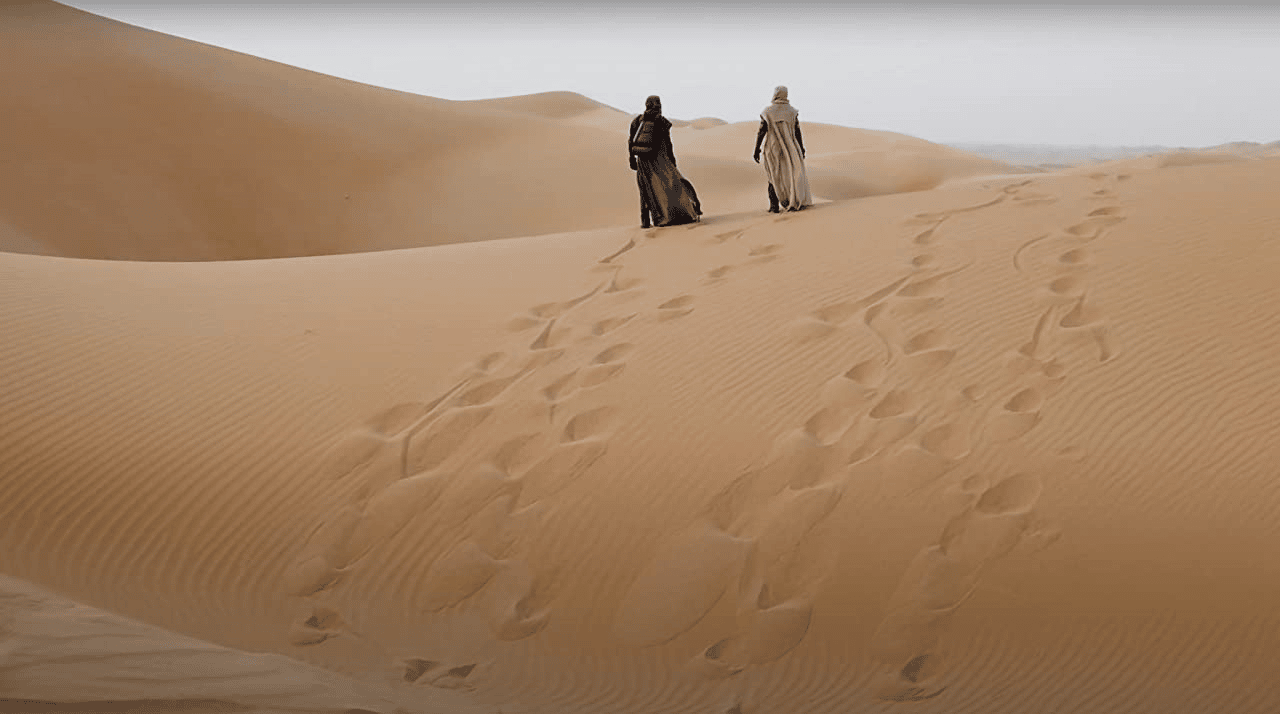

Lynch’s film presents a series of cluttered, claustrophobic interiors with brief excursions into a desert that often seems as crowded as the rooms the characters plot in. Villeneuve, by contrast, presents a positively expansive, sun-drenched Dune appropriate for the IMAX format. Long aerial sequences of vast desert landscapes contrast with bare, dimly-lit, minimalist interiors with great, Vermeer-esque beams of light illuminating the scene. Villeneuve has also jettisoned the mannered speech and the endless internal dialogues of the novel that Lynch tried to portray faithfully, substituting more accessible, naturalistic speech, while reserving many of the important phrases of key scenes and famous mantras from the book. Given the way people speak to each other (and simply to themselves – a lot) in this world, it’s a natural way to make things more accessible for the casual viewer who has a lot to take in already, without developing an ear for the often strangely stilted way people express themselves in the book. Toning down the classic Herbert internal dialogues which detail each character’s thought processes and suspicions of each other into more contemporary speech also risks losing some of the classic Dune flavour and some aspects of the world-building, but overall, it works. Each key scene, from Paul’s training sequence knife with Josh Brolin’s gruff Gurney Halleck on Caladan, where he learns mood isn’t a concern, to the infamous gom jabber ‘is he or isn’t he the Kwisatz Haderach’ torture box scene, to the scene where the kidnapped Paul and Jessica work together using the mind-manipulating ‘voice’ to free themselves from certain death at the hands of Harkonnen goons, still retains the essence of the book with key phrases dropped in.

There’s a necessarily huge amount of exposition in Dune that simply cannot be helped, given the cast of thousands and the political structures and players in a complex universe that needs to be rendered comprehensible by the mainstream viewer, if they are to make much sense of what is to come. It’s a problem both directors clearly wrestled with. Lynch opened with a monologue explaining the main players and their issues. Villeneuve gives you a monologue too, but only after setting out his artistic stall with a blank screen, a guttural voice speaking an unknown, alien language and a line of subtitles making some cryptic reference to dreams, as if to remind us that this is Dune and we’re going to have to just roll with a certain amount of weirdness and incomprehensible moments here. Villeneuve, much like Lynch, frontloads the film with exposition done cleverly through dialogue and – as in Lynch’s version – the spectacle of Dune’s informative ‘filmbooks’ which Paul uses to learn about the new planet – a concept that probably seemed still out there in the 1980s but which technology has caught up to now. What was the equivalent of a modern tablet and internet with voice recognition is now a delicate and beautiful holographic surround. There’s a lot of visual information in the film that suggests it will benefit greatly from close and repeat viewing.

Other stylistic choices play heavily into the successful characterization and world-building of Villeneuve’s Dune – specifically that of Lady Jessica, concubine of the doomed Duke Leto, and their sworn enemies, the Harkonnens. What struck me is how heavily Villeneuve has Rebecca Ferguson’s Jessica lean into the Bene Gesserit side of her character rather than – as in the Lynch version – the deeply sensual, seductive and elaborately coiffed and robed courtesan. His Jessica is practically ascetic in appearance; bare-faced, given to plain, functional clothing, with the luxurious aristocratic gowns reserved only for occasions in which she is overtly seeking to impress an audience, rendering them oddly functional costuming rather than an essential extension of her femininity. See the scenes when she and Paul escape into the desert – Lynch’s Jessica draped suggestively in a silk and lace Victorian-type nightdress; Villeneuve’s Jessica clad in what look like IKEA pyjamas. The scenes in which she sternly instructs Paul in his Bene Gesserit voice skills are a joy of showing rather than telling. Villeneuve portrays Jessica as fiercely self-possessed, not suffering fools gladly or at all, but also cowed and almost unhinged by the presence of her own Bene Gesserit mentor, the terrifying Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam – Charotte Rampling giving magnificently pissy and cynical boss vibes from behind a series of veils and tall hats. In Jessica’s fear of Mohiam, as well as her skills, we glimpse the secret power of the all-female Bene Gesserit order in this otherwise heavily patriarchal world. Rampling’s Reverend Mother, while ostensibly a hand of the galactic Emperor, is clearly a major power broker in her own right who even the Harkonnens tread carefully around.

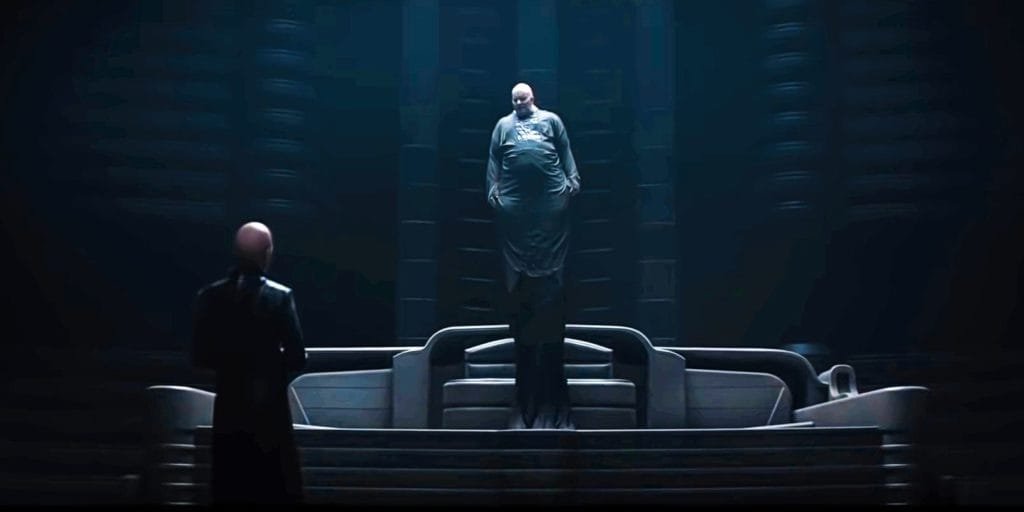

Oh yes, the Harkonnens. In contrast to Lynch’s marvellously intemperate and pustulant ‘floating fat man’ (played with shouty relish by the late Kenneth McMillian), Villeneuve shows us a far more horrifying vision of the notorious Baron Vladimir as a quietly sociopathic narco-lord who is so lost to corruption, his very physicality seems to be veering away from the human and into the bestial. Draped in an absurdly trailing silk kaftan, he rears up from his throne like a giant cobra; he emerges briefly, gurgling, from a bath of oil like some off-putting, bloated sea creature washing up from the deep; he keeps a nightmarish, perhaps fully sentient, spider/human-hybrid-looking thing (perhaps a visual nod to the secretive Tleilaxu, another set of sinister power brokers who will become significant in the Dune universe later) as a ‘pet’, and in perhaps the most visceral image of the entire film, he is found clinging high up a wall like a giant mollusc or horrific human cockroach to survive an impromptu gas chamber experience created by the dying Leto. Villeneuve further nails the portrayal by contrasting the naked, masculine beauty of Oscar Isaacs’ captured Duke Leto with the grossness of the vile, morbidly obese baron in a beautifully-lit tableau that resembles a monumental baroque painting. The Baron, stuffing his face in greedy ecstasy, leering over the Duke in his martyrish repose, laid out like the next course at the Baron’s feast. In that one shot we see nobility only goes so far in this universe, while brutality and cruelty gets you far further.

Perhaps the only places Villeneuve falls down is in his decision to cut short the Atreides internal intrigues on Arrakis before their fall. Doctor Yueh is tragically given such short shrift that his betrayal fails to shock as it should, or demonstrate the sheer heartlessness and cleverness of the Baron in undermining House Atreides through short-circuiting Yueh’s Imperial conditioning by playing on the very human empathy that is supposed to render him incapable of causing harm. Lynch gave Yueh’s fatal decision more weight and sympathy in allowing him screen time and more scenes interacting with the various Atreides as their loyal and trusted Suk doctor. In fact, both directors seem to have had to make a choice to sacrifice some significant character development or vital scenes to keep the film within its allotted screentime. Lynch chose to keep many of the Atreides character building scenes in the first half and truncated or eliminated a lot of the significant action – such as the absolutely pivotal fight with Jamis – after Paul and his mother reach the desert. Villeneuve appears to have filmed several significant scenes that belong in the middle portion on Arakkeen. Several tantalizing photos of Yueh interacting further with both Jessica and Paul have been released, as well as the news that a significant scene set around a banquet was actually filmed and then completely excised in favour of extending the action in the desert and expanding imaginatively on Liet Kynes’s fate. The mentats Thufir Hawat and especially the Baron’s Piter de Vries also seem underserved by Villeneuve’s final cut, especially given Thufir is rather important in the second part of the book. Their skills aren’t really shown or explained much beyond Thufir doing some serious mental arithmetic on Caladan. There is sadly no mention of the ‘juice of saphu’, the plant-based drug that mentats use as a thought-amplifier, another bit of Dune lore that roots its creation in the 60s counter culture. Villeneuve’s Piter (David Dastmalchian) comes off as less the highly intelligent and deeply perverted schemer responsible for turning Yueh traitor in the book and more a scared, bug-eyed aide, who cacks it far too quickly and is forgotten in this cut. Possibly like Chang Chen’s Doctor Yueh, most of his development ended up on the cutting room floor. Stellan Skarsgard is admittedly a hard act to compete with to be fair, although Lynch’s Brad Dourif may have stood a chance.

However, we need to recognise that Lynch was trying to cover the entire book in just over two hours, while Villeneuve had the luxury of only serving half the text in a lengthier film. Still, it shows that Dune is so rich in character and narrative that there’s always something that is going to end up on the cutting room floor for reasons of pace or time, even if it slightly weakens the narrative. Not that you can really fault Villeneuve on pacing – a strength of the film and likely part of its success is that it moves fast, keeps moving, and doesn’t get bogged down at any point. This middle section of the film is the only one that feels somewhat thin and rushed, and vaguely disappointing in retrospect, despite serving up some incredible visuals as the combined forced of the Harkonnens and the Emperor’s terror troops attack the Atreides, precipitating Paul and Jessica’s flight into the desert and their confrontation with the Fremen that ends the film.

The Fremen, the indigenous people of Arrakis – or rather the framing of them in the narrative – is one of the most interesting departures from the book and the Lynch adaptation. While Lynch presents them as the exotic backdrop and eager allies for the ascendant prescient superbeing Paul’s personal revenge quest and successful, uncomplicated prophecy completion, Villeneuve actually centres the Fremen in the story from the beginning. They are the first people we see and the first intelligible voices we hear, speaking to us directly. They are presented as a militantly rebellious desert people whose culture revolves around the kind of harsh decisions that promote survival. Stilgar, their tribal leader, is perfectly embodied by Javier Bardem as charismatic physical presence with a natural contempt for and apparent disinterest in his imperial-appointed overlords. While Lynch’s opening narration and vital expositional scene-setting is done from the viewpoint of the powerful, the Emperor’s daughter Princess Irulan, the novel’s historian, Villeneuve breaks from the text and substitutes the young Fremen girl Chani’s (Zendaya) viewpoint. Chani – who was really little more than a fetching love interest in Lynch’s film – is concerned with her planet’s occupation and colonisation and her people’s ongoing cultural genocide at the hands of what the Fremen view as interchangeable, oppressive foreign occupying powers, concerned only with the mining of the precious spice. Chani’s monologue is eerily and uncomfortably resonant and perhaps prescient itself of the recent American withdrawal from Afghanistan, where, like the Harkonnens, they suddenly and without notice, disappeared in the middle of the night.

So it is that Paul Atreides enters Chani’s world framed as yet another loathed occupier and possible ‘Mahdi’ (messianic figure), and where Villeneuve picks up on a vital plot strand that Lynch ostensibly ignored; that the tribal legends of the messianic ‘Lisan al Gaib’ (The Voice from the Outer World) and his Bene Gesserit mother, whom Paul and Jessica are suspected by the Fremen as fulfilling, did not evolve organically within Fremen culture. These messianic prophecies, their signs and portents, are in fact part of a long-term strategic effort by the Bene Gesserit known as the Missionaria Protectiva. The order seeded superstitions into many worlds, including deep into Arrakis’s Fremen culture, that can be exploited by their order in a time of need. Villeneuve has both Jessica and Mohiam obliquely and directly refer to this plan at various points. So, while Paul is increasingly aware of his powers, aided by the psychotropic nature of the spice that lends him prescience to see into his own and others’ futures, where he begins to progress past his mother’s teachings and beyond her control, he appears slightly less the noble hero and perhaps more the beginning of a cautionary tale on the theme of the inherent dangers of charismatic leaders – or assumed messiahs – Frank Herbert’s central theme in Dune. It’s played out in a fantastic scene where Paul, lapsed into a spice trance, experiences traumatic visions of the carnage inflicted on endless worlds by the insane galactic holy war conducted in his name that he will be unable to stem or control, if he remains on his current course.

Note, in the book it’s specifically a jihad, a word used liberally in the original novel(s) and used by Lynch, but Villeneuve sadly avoids any use of it for what are likely obvious religious and political sensitivities these days, while staying with all the other Arabic loan words in the Fremen lexicon and Dune universe. The world was a little different back in 1984, obviously, but it’s a little disappointing given ‘jihad’ is a foundational concept in the Dune universe, used to explore the warping effects of religion on society, going back to the original ‘Orange Catholic Bible’ proscription against ‘thinking machines’ that resulted in the abolition of all computers and the creation of the mentat schools, the Spacing Guild and the Bene Gesserit themselves. I guess ‘holy war’ will have to suffice. At least Hans Zimmer has given us a cool tune of the same name. Toto and Brian Eno on Lynch’s soundtrack were actually great, as the sheer rock bombast does suit the film’s scope, but Zimmer is a cut above in reflecting the strangeness of the Dune universe in his choice of odd and eerie soundscapes.

Beyond these grim and dark themes, however, Dune presents a highly accessible coming of age story. Paul’s journey from innocent youth into manhood through a series of trials and tribulations is highly relatable stuff. His journey to becoming a superpowered being via thousands of generations of conspiratorial genetic manipulation isn’t too far of a stretch in a modern era of genetic engineering and an audience soaked in ten solid years of superhero tentpoles. Timothy Chalomet is certainly naturally charismatic and wild-eyed enough to sell the idea of the slight aristocratic boy troubled by strange dreams, becoming hardened by experience, the loss of his father and all his male mentors, and further burdened with the knowledge that he has a rather sinister genetic legacy via his remaining parent’s machinations. He is well-matched by Zendaya as the Fremen girl whose face haunts his visions. Villeneuve’s casting decisions seem again designed to appeal to a young general audience, while throwing in enough excellent older character actors to appease those of use to whom the Timothies and Zendayas were never designed to appeal.

It will certainly be fascinating to see Dune Part 2, greenlit a week ago now, in 2023. The first film has hopefully laid enough groundwork and done enough world building to dig deep and with brio into the remaining plotlines from the second half of the book. Beyond that, can one dare dream of a third film, an adaptation of the shorter, more miserabilist sequel Dune Messiah? It could possibly function as the biggest downer sequel ever. Fans of Tim and Zendaya may not enjoy it at all. Then there’s the third book, Children of Dune, which marks the return of more than one character you thought you’d seen the last of in Dune. I’d hesitate to say this could be this generation’s Lord of the Rings in film terms, but given the impossibility of what Villeneuve has already achieved bringing Dune to the screen, who can tell? Stay tuned. Denis may yet pull it off again, and again, and again …