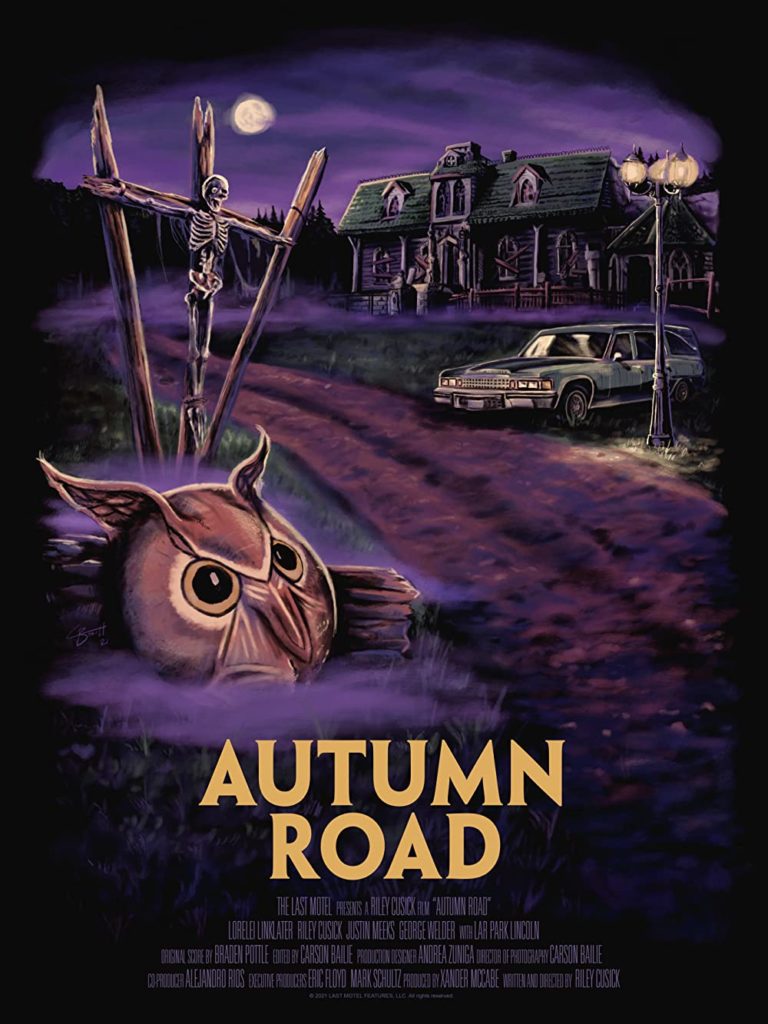

There is a germ of a decent idea in Autumn Road, a film which comes across, at least at first, as a love letter to small town Halloween. Indeed, it’s an attractive film, with some great settings, and some careful sleight of hand which provides some interesting sequences. Unfortunately, all the Halloween aesthetics in the world can’t stand in for a plot or good performances, nor can they replace a script or a judicious edit. This is a film which, although coming in at just over the sanctified ninety minutes, feels far, far longer.

It starts reasonably enough, with two brothers, Charlie and Vincent, whose dad runs a Halloween attraction. Their friend Winnie (Maddie-Lea Hendrix) spends a fair bit of time at the Graystone house, and heads off to Trick or Treat with Vincent, with Charlie making his excuses. When they get back, Winnie goes to see Charlie, who likes hanging out in a hearse; she gives him one of her candy bars, on the grounds that she is severely allergic to peanuts – but then seems to forget this life-threatening ailment when she lets Charlie kiss her, triggering her anaphylaxis. Charlie flaps about, darting out of the car to ask his brother to help – which, for reasons which still elude me, he declines to do, letting the girl die and promising Charlie he’ll ‘take care’ of the situation. Charlie seems to take this sudden turn of events quite well too: it simply makes no sense. But anyway, we now move forward in time.

We’re privy to an audition going really quite badly, something which I thought was deliberate to show that the actor in question really couldn’t act – but then this standard of performance continues throughout the film with an oddball, flat and detached delivery from Lorelei Linklater (it gives me no pleasure to say as much, but it really is staggering). Laura – for it is she – doesn’t get the gig, and her roommate tells her they should just write a film of their own, which they begin to do before a (presumably, completely unintentionally hilarious) accident cuts this plan short, sending Laura back to her home town to reconnect with her mother. When she gets there, she instead reconnects with the now grown-up Charlie (director and writer Riley Cusick): turns out Laura is Winnie’s sister, and she has such a rough time getting on with her mother as a result of the girl’s disappearance that fateful Halloween. So there we have it: Charlie has lived this whole time largely untroubled by being an accomplice to his brother, Vincent (also Cusick, for they are twins) is the unpredictable, violent one, and Laura understandably has questions about her sister’s disappearance.

That’s it. The possibility that Laura was going to continue to write her screenplay, working through her own trauma in the process, or supernatural phenomena was going to lead her to Winnie, or even that she was simply going to find out what happened to her, does not come to pass as expected. There is a lot of talking, and a lot of head-scratching moments which compound the initial, unbelievable plot point where two kids preside over a death by layering on other, smaller, equally implausible scenes. The guy Vincent punches in the face, simply wandering off without being particularly bothered by his assault…the girl who angrily quits her job but is right back there the next day…Vincent heading off to attack one of his co-workers wearing a disguise that the same co-worker would see him in every single day at work…these sorts of things just need to be ironed out when reading through a screenplay, but then when the writer, director and acting lead is one and the same person, this process often becomes diffuse, it seems.

There are, eventually, some answers, but by this point the relative lack of plot and the wildly differentiated performances (where Laura is flat, Vincent is depicted as a wild-eyed, leering danger) have extinguished the film’s initially engaging premise. This is a shame, as there was a lot of potential here with a setting which would do any horror fan’s heart good, but it’s not enough on its own. It’s not immediately clear what the title refers to, either, but really, that’s not the most pressing of concerns.