Note: unusually for the site this review contains mild spoilers – words failed me else – so read on with caution.

On first consideration, Julia Ducournau’s new film, Titane (2021) is quite unlike Raw (2016), her last feature and, for most people, the most familiar point of comparison. To put it mildly, Titane is an odd beast, where much remains unexplained; on first impressions alone, it all feels rather thinner than Raw, with less clear subtext and symbolism. However, there is some overlap, with many of the most satisfying moments of the newer film stemming from this: the twisted, but oddly redemptive family dynamic, the strong, if often mystifying female lead and the excruciating focus on the body all lead to some satisfying sequences. My main criticism of Titane is that it does feel like a series of sequences rather than a solid storyline, but in the madness of how it all unfolds, there’s a great deal to make your jaw drop. It’s very uneasy viewing, and it keeps you guessing at where on earth it’s all going. (You may not feel that you know the answers to those question when the credits roll, mind you.)

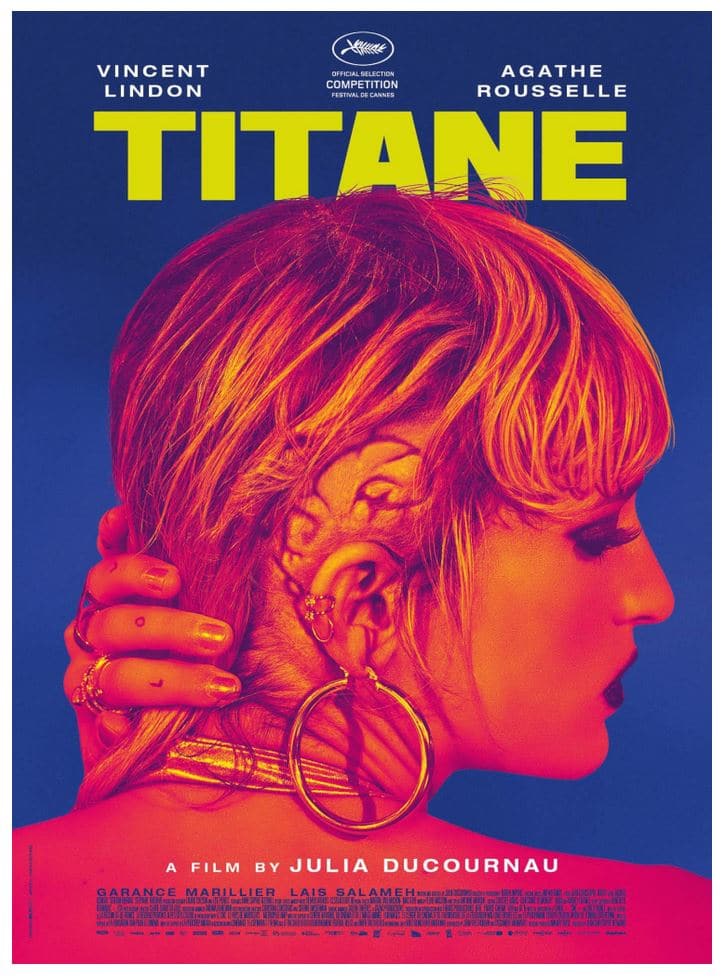

As the film begins, we’re certainly not encouraged to like Alexia, played first as a little girl (and compellingly so by Adèle Guigue). Alexia decides to distract her father whilst he’s driving; not long after the film starts, this causes an accident, after which the seven year old girl has to have titanium plates put into the side of her head. She glowers at her father after the operation, not seeming to understand that she played no small part in this, but one thing’s for sure – this is no loving, conventional family home. Flash forward: Alexia is now a woman (the rather intimidating Agathe Rousselle). She still lives at home, to dad’s clear dislike, and makes a living bumping and grinding on a car as a dancer. Apparently, this is a thing, and imagine that conversation with the insurance. Alexia is more or less silent and closed off, but knows how to dance, coming alive when she does – then closing down again when the music ends, a strange, formative sex scene involving a car notwithstanding. We see a dark side to all this when she’s pursued by a man who doesn’t seem to understand ‘no’, and we also see that Alexia will take strong measures to defend herself, perhaps reasoning that only ultraviolence will reset the balance.

Any expectations that this will be a linear consideration of how women navigate the world and its male entitlement are soon scuppered, however; for whatever reason, it seems that Alexia has had enough of her lot, but to make her escape from it, she begins to progress through different roles. The first is as a grand failure at human empathy, leading to scenes of barbaric, inexplicable violence against people who do not deserve it (one criticism I have about the film is in how it seems to lob in characters only to dispatch them, whilst simultaneously reaching for deeper significance which eludes it precisely because of its unwavering focus on the suffering of innocents). After this, she flees her old life by disguising herself as someone else – a son, Adrien, who has been missing since childhood, reuniting with his father. More ultraviolence accompanies this transformation, but then the film segues more into an examination of how Alexia behaves as Adrien, whether she can maintain the pretence – and why she chooses to.

Shades of Calvaire (2004) creep in here, as the wonderful Vincent (Vincent Lindon) persists on believing Alexia is his son, leading to some strange comedy of errors moments but showing that Vincent, too, is a damaged man who would believe in his son come what may. The very male environment of the fire station over which Vincent presides affords some funny moments, particularly when Alexia resorts to type and dances for ‘the guys’ just like she would have done as a girl. But there are also lots of poignant moments, too. Gradually, these two strangers develop an affinity for each other which is very pleasing, and counterbalances the rather jagged first half of the film.

Much has been made of the gender subtext used in Titane, but despite the very real issues relating to Alexia convincingly appearing as a male, it seemed more about expedience than anything else – a convincing disguise as a means of escape. This is something, though, which would certainly withstand a second viewing, as more may yet come to the fore. First impressions? Gender is there, but deeper significance seems to have been mooted, rather than anything else. Similarly, the fantastical elements are entertaining, but left unexplained, and these at times jar against the plausible human relationships which spring up later. It’s a feature which may need more unpacking with a revisit. Should a film need multiple viewings to work fully? It depends, probably, on what comes out on these multiple viewings.

So at the end of this admittedly meandering review, the first-viewing verdict is mixed on Titane, despite it being a film which can take some pondering. That is perhaps its saving grace, that it generates a lot of reaction, even if some of that is questioning. For all the bellyaching, it was a fascinating watch and the more I’ve tried to pull it apart, the more I like it, on reflection. Extra credit to Rousselle, here in her first film role, terrifying and vulnerable by turns. Ducournau may have changed tack here, but it’s another impressive, thought-provoking piece of work.

Titane (2021) screened at the Celluloid Screams film festival in Sheffield, UK.