By guest contributor Caitlyn Downs

Twice delayed by the pandemic, Antlers has likely been on the radar for many horror fans for some time, thanks in no small part to the involvement of producer Guillermo del Toro and the promise of the kind of magic creature horror that he is so well known for. Those looking for that del Toro stamp here may be left wanting, with a feature that falls short of the richness expected.

“Don’t take what isn’t yours” is a major preoccupation of Antlers, with that ranging from what humans take from one another, from nature and how this impacts the world around it. This places it within a context of other recent release films that, perhaps understandably given climate concerns, have sought to reflect the earth returning to wrest control from the humans that have damaged it. The threats are multiple within Antlers, with the focus of the mining town resulting in poor jobs, poor finances, plus pervasive addiction and abuse issues that scar everyone. The film’s shifting focus from this wider, global concern to something more intimate and small-scale across two families ultimately serves it well, allowing it to do less than if it had to explore the entire town.

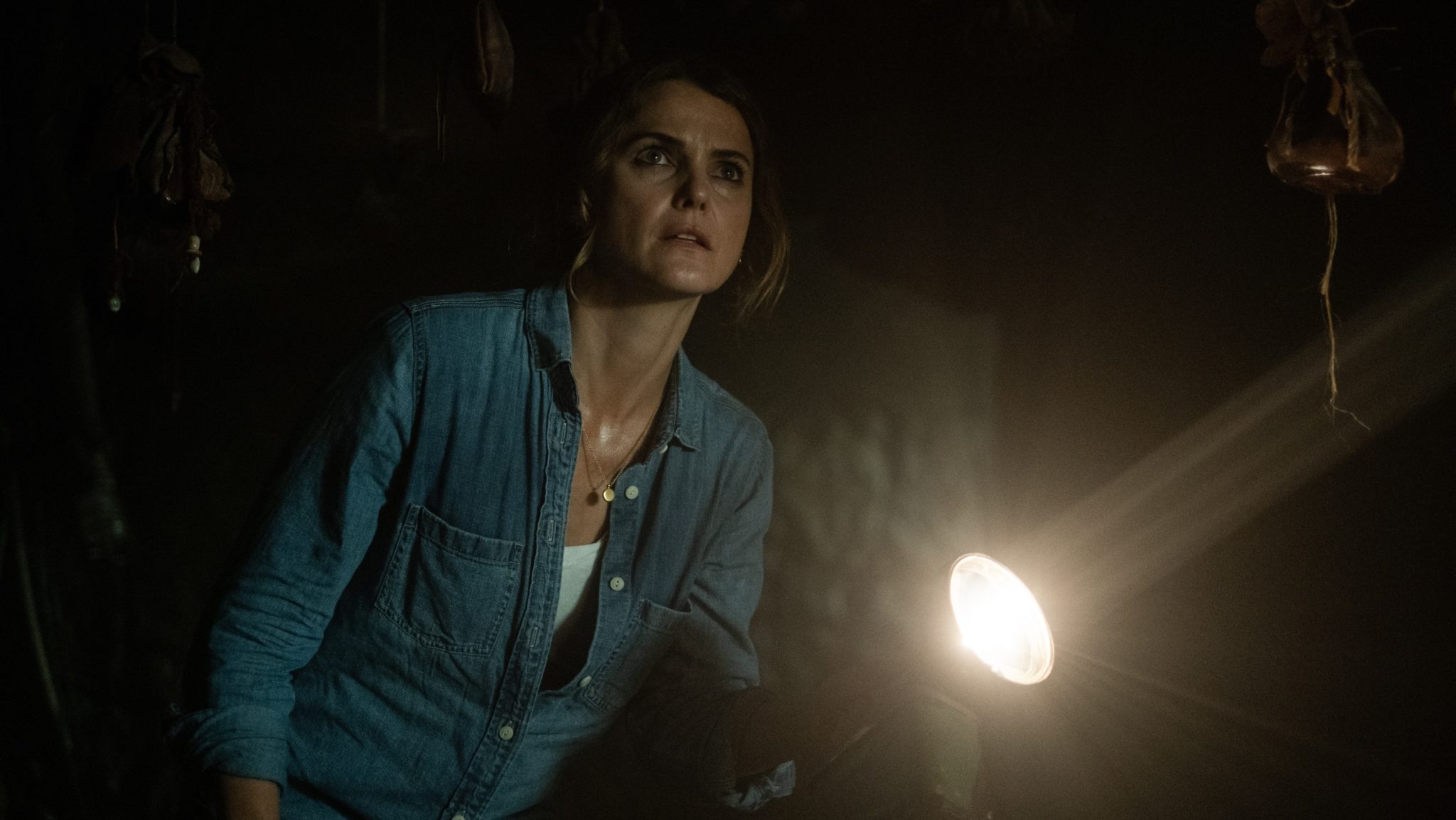

The use of spiritual entities that form the belief system of marginalised cultures in mainstream film is, understandably, a thorny issue. As a white woman based in the UK, I can’t offer too much comment in how respectful or accurate the portrayal is here, or in Nick Antosca’s original short story The Quiet Boy that forms the basis for this story. Having done some reading and viewed the Comic Con at Home 2020 panel for the film released ahead of the film’s release, it seems that First Nations consultants (including Grace L. Dillon and Chris Eyre) were afforded a say in the role of the entity, especially in terms of educating director Scott Cooper on its deeply held importance. It is something of a shame, then, that the bulk of the story is focused on non-Indigenous characters. Aside from Warren Stokes (Graham Greene bringing suitable gravitas) who appears to provide an explanation and grave warning, we primarily focus on Julia (Keri Russell), sheriff Paul (Jesse Plemons) and Lucas (Jeremy T. Thomas).

Keri Russell gives an engaging performance as Julia although there are moments where the film uses shorthand that leaves her with little to do. For example, her alcoholism is showcased almost exclusively by her looking sadly at bottles in the local shop, but never feels like it represents a significant enough threat to impact the rest of the narrative. More interesting is the shared abusive history she shares with brother Paul and the way this becomes the source of tension and miscommunication between the pair. Plemons is ever reliable and while this is hardly a role to stretch him, he brings a necessary presence and a good chemistry for the strains with Russell’s character. The echoes from their past are carefully positioned within the narrative but never quite overcome the repression that would arguably free them from it. The real star of the piece is Jeremy Thomas who, despite his youth, turns in an impressively nuanced performance, perfectly embodying Lucas as a young boy ill at ease in the world and within his own skin.

The location provides a beautiful, if ominous setting for the story to unfold – the lake lending it a remoteness and the woodland shrouding it in darkness for much of the time. That reliance on woodland extends into homes, the wood often left bare and unwelcoming (especially as it finds itself with a layer of blood and viscera). The elements of the location suitably become part of the entity design too, lending the film a sense of cohesion and connection to the source of that belief system. The area feels all-encompassing, encasing the characters in an oppressive cycle that draws them all to darker impulses. As already referenced, however, Julia’s struggle with alcoholism is dominated by her almost instant maternal instinct towards Lucas who she notices struggling in the classes she teaches so some of this darkness is reserved for other characters who are not needed to drive the plot.

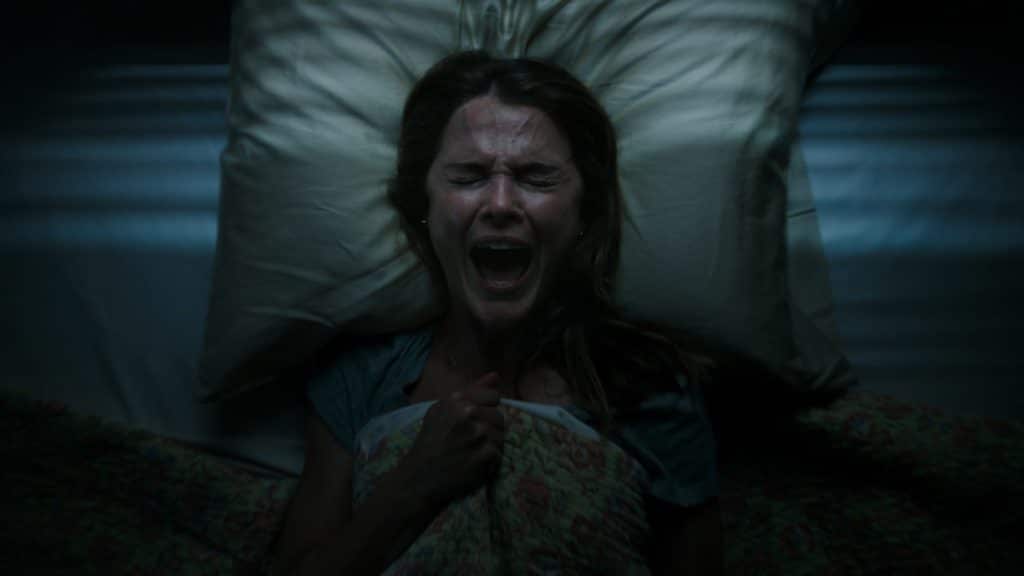

Despite its mainstream positioning, Antlers does not feel like a blockbuster horror offering and that may well hurt it with some audiences. The scares escalate in the third act, including an excellently timed jump scare that proves Cooper’s ability to deliver on that style as much as the quieter building of tension and menace, but this follows a longer time period of mood-setting. The gorier elements too, especially when coupled with the downbeat tone hardly makes this a fun night at the multiplex, so it is refreshing in that sense to see something like this given further attention. In addition, there are vital beats of the film that thrive on characters making ill-advised decisions, which while always a part of horror particularly stand out within the confines of a relatively small cast. Despite the emotional weight the film aims for and the misery it indulges in for much of the runtime, so much of the narrative feels like a foregone conclusion that you almost resign yourself to that in early scenes and by the end, despite that final burst of energy, you’re left with relatively little to hold on to.

Antlers released in UK cinemas on October 29thand screened as part of the Celluloid Screams film festival in Sheffield, UK. You can check out more of Caitlyn’s writing here.