Starring former Captain America Reb Brown[i], the 1986 ‘macaroni combat’ picture Strike Commando, now available on an exemplary Blu-ray release from Severin Films, is one of a number of pictures that Italian film director Bruno Mattei – that auteur of so many awful-but-oh-so-watchable Italian exploitation films of the 1980s and 1990s – made in the Philippines with producer/co-director Claudio Fragasso, and writer Rosella Drudi.

Italian combat pictures (or ‘macaroni combat’ films, as they are sometimes called) had been fairly popular since the 1960s, often starring ‘over the hill’ English-speaking actors in Second World War-set stories. Essentially Commando comic strips brought to life, many of these pictures were vaguely – or not so vaguely, in some cases – reminiscent of Robert Aldrich’s iconic combat picture The Dirty Dozen (1967): in other words, they featured ensemble casts in ‘men on a mission’ narratives. Like the commedia sexy all’italiana, the macaroni combat films were never as popular with either domestic or international audiences as other exportable filoni of Italian pop cinema – chiefly, the westerns all’italiana (‘Spaghetti Westerns’) or gialli/thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thrillers)of the 1960s and 1970s. However, many of these films – including the likes of Gianfranco Parolini’s Five for Hell (5 per l’inferno, 1969) and Maurizio Pradeaux’s Churchill’s Leopards (I Leopardi di Churchill, 1970) – have nevertheless earned a cult following in the years since their initial releases.

A sea change occurred in the early 1980s when, influenced by the one-two punch of Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), Italian combat films lost interest in the Second World War and became instead fixated with the Vietnam War. (This, of course, neatly sidestepped the fact that many of the earlier Italian war films had, in using The Dirty Dozen as their key source of inspiration, involuntarily been shaped by a film that used its Second World War setting to comment on the era of American military involvement in Vietnam.) Further to this, the production of Apocalypse Now in the Philippines had created a local filmmaking infrastructure ripe for exploitation, and Italian filmmakers were quick to jump on this, using the jungles of the Philippines as a stand-in for Vietnam. In 1980, Antonio Margheriti’s Vietnam War-set combat film The Last Hunter (1980), shot in the Philippines, was one of the ‘macaroni combat’ films to trigger this trend in ‘Namsploitation’.

Its narrative clearly modelled on that of Apocalypse Now, with a heavy dose of the love triangle from Sergio Leone’s Duck You Sucker (Giù la testa, 1973) for good measure, The Last Hunter was marketed to Italian domestic audiences as a loose sequel to The Deer Hunter: where Cimino’s film had been released to Italian cinemas as Il cacciatore, the Italian title of Margheriti’s picture was L’ultimo cacciatore. (In fact, promotional materials for the film exist which bear the more on-the-nose title Cacciatore 2, though it is unclear whether the picture was ever formally released under that title.) Many of the subsequent Vietnam War-set Italian combat films owed a considerable debt, in terms of narrative or sometimes in the staging of specific sequences, to Margheriti’s The Last Hunter. Going so far as to utilise footage cribbed from The Last Hunter, Mattei / Fragasso’s Strike Commando is no exception to this, though the core of Strike Commando narrative is cribbed from a more recent American model, George P Cosmatos’ Rambo: First Blood, Part II (1985).

Credited to Mattei’s well-worn Anglicised pseudonym ‘Vincent Dawn’, though in actuality co-directed by Mattei and Fragasso, Strike Commando opens with the betrayal of Major Harriman’s (Mike Monty) highly trained special forces team (the titular ‘Strike Commando’ unit) in an excursion behind enemy lines. This betrayal comes at the hand of rival Air Force Colonel Radek (Christopher Connelly), who is jealous of the Strike Commando unit’s many successes. However, one of the team survives: Harriman’s prize soldier Ransome (Reb Brown). Left for dead, Ransome is rescued by a young South Vietnamese boy, Lao (Edison Navarro), and is taken in by South Vietnamese villagers, led by Frenchman Le Due (Luciano Pigozzi) and including Cho Li (Karen Lopez).

Separated from US forces, Ransome nevertheless finds a working radio when he, and the villagers traveling with him, stumble across the corpse of an American chopper pilot. He uses this radio to make contact with the US base. Harriman persuades a reluctant Radek to rescue Ransome. However, back at the US base, Ransome is ordered to head back into the combat zone to investigate claims of a Russian military presence in the area. Back in the fray, Ransome is taken captive by a Russian operative, Jakoda (Alex Vitale), a KGB agent who is working with the NVA. Jakoda tortures Ransome, hoping the Strike Commando will broadcast anti-war messages to US troops. However, Ransome manages to escape with Jakoda’s female counterpart, Olga (Louise Kamsteeg). Olga quickly falls for the hunky American, and aids him in his escape. However, Ransome is once again betrayed by Radek, who commands a chopper gunner to shoot Ransome rather than order his rescue. Olga is killed, and Radek’s betrayal reaffirms Ransome’s desire for revenge.

‘It’s getting tight’, Radek tells Harriman as the film opens. ‘It was tight to begin with’, Harriman responds. Both men watch the Strike Commando unit infiltrate the NVA compound from an observation position which would seem to be all-too-visible to a watchful enemy. Mattei / Fragasso would seem to be either suggesting that the NVA forces are deeply, profoundly unobservant – or, with the film’s opening minutes, willingly sacrifice any pretence of realism. All bets are on the latter, given the joyful, nihilistic absurdity of what ensues. This extends beyond narrative events to the equipment used by the characters in the film, including a pair of binoculars which, when we see through them from Ransome’s point-of-view, make a computerised whirring noise and feature a readout of numbers on the right-hand side, but have no clear benefits over normal ‘bins’.

The parallels with Rambo: First Blood, Part II are writ large. If Ransome is a poor man’s Rambo, Christopher Connelly’s Colonel Radek is a sneering imitation of Charles Napier’s duplicitous Marshall Murdock, the CIA field operative who sends Rambo into Vietnam to collect evidence of long-held American POWs; and Major Harriman, who acts paternalistically towards Ransome and refuses to abandon him, is a cut-price Colonel Trautman (Richard Crenna). Furthermore, the film’s sadistic Russian antagonist, Jakoda (Alex Vitale), is an all-too-obvious pastiche of Steven Berkoff’s Lt Col Podovsky (by way of Richard Kiel’s Jaws, from The Spy Who Loved Me); both characters serve in their respective narratives as symbols of Russian support for / orchestration of the NVA forces in Vietnam.

Strike Commando hits all the major narrative beats of Rambo: First Blood, Part II. Like Rambo, Ransome is sent behind enemy lines, and betrayed by a slimy, self-serving member of his own team. Cut off from US forces, Ransome is forced to work with local guerrilla operatives and uncovers evidence of a Russian presence in Vietnam. Taken captive by a Russian officer, he is tortured with the aim of making him broadcast a message to US forces, dissuading further action in the region. However, he escapes and returns for a confrontation with the man who betrayed him.

Like Stallone’s John Rambo, Ransome also has a tendency to yell / growl / scream[ii] animalistically whilst enacting his vengeance, wielding an identical belt-fed machine gun (an M60) which he shoots from the hip on full auto. (So macho, as Sinitta sang only a couple of years earlier, in an equally iconic piece of mid-80s fluff.) The absurdity and lack of subtlety of this is actually confronted directly within the film. After returning to the combat zone with the mission to prove the Russian presence in the region, Ransome forces an NVA regular to him to Jakoda. Ransome is directed to a small village. Emptying his M60 (from the hip, on full auto, as above) at the huts (whilst yelling ‘JAA-KO-O-DAAA!!!!’), Ransome finds himself spent as NVA regulars surround him, and Jakoda makes his appearance (‘You looking for me, Americanski?’): they have been hiding everywhere but in the huts that Ransome has destroyed.

Strike Commando extends Rambo: First Blood, Part II’s conclusion, however, with the film’s final sequence taking place in Manila, some time after the main events of the narrative. Ransome tracks down Radek, who is now running an import/export business. Carrying the aforementioned belt-fed machine gun, Ransome rips through the offices in a scene clearly inspired by the sequence in James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) in which Arnold Schwarzenegger’s T-800 destroys the police station in which his target Sarah Connor is being held, before blowing Radek away with an underbarrel grenade launcher. Leaving the building, Ransome encounters Jakoda, who has miraculously survived his previous encounter with Ransome, and who now wears a set of steel teeth clearly paying homage to Richard Kiel’s Jaws in the James Bond films The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker. Ransome crams a grenade into these dentures, telling Jakoda, ‘Ah, shut up!’ Jakoda explodes in a shower of grue, managing to cry ‘Americanski!!!’ even after his torso has been obliterated by the grenade. The steel teeth land in Ransome’s upturned palm. ‘These Russian dentists make some pretty good dentures’, Ransome quips, and the film ends with that (intentionally?) corny James Bond-style one-liner.

Mattei, Fragasso and Drudi paint the narrative in broad strokes, drawing on caricatures for characters and dialogue. ‘You know, when I used to steal watermelons down in Alabama, I used to have to climb fences, not cut them’, the only black member of the Strike Commando unit quips as the team sneak into the NVA compound in the film’s opening sequence.

The film depicts the complex circumstances of the war in Vietnam in equally cliched, highly simplified terms, regurgitating the reductive narrative of Rambo: First Blood, Part II and its contemporaries, such as Joseph Zito’s Chuck Norris action-er Missing in Action (1984) and its sequels. Ransome is depicted as the ‘white saviour’ of the South Vietnamese, whilst the North Vietnamese forces (and NLF guerrilla fighters) are largely little more than a nuisance – cannon fodder for Ransome’s M60 – who have so little agency that their every action is dictated by Russian interlopers. When Ransome is discovered by Lao and taken into the South Vietnamese village, Lao introduces the Strike Commando: ‘He’s American, our saviour!’ In response, the villagers excitedly chant, ‘American! American!’ However, they are disappointed when Ransome refuses to captive enemy agents – who don’t appear to be NVA regulars, and instead must be South Vietnamese NLF guerrilla fighters (or Viet Cong). However, Ransome refuses: ‘Why should I kill an unarmed man?’, he asks his new allies. Cho Li is frustrated by this: ‘That man is a demon, and I never take a demon prisoner. He is your enemy, American. He hates and he kills’. Afterwards, Le Due explains to Ransome that the villagers ‘were hoping you’d be their saviour [….] That’s why your gesture, your humanity towards the enemy, has let them down’.

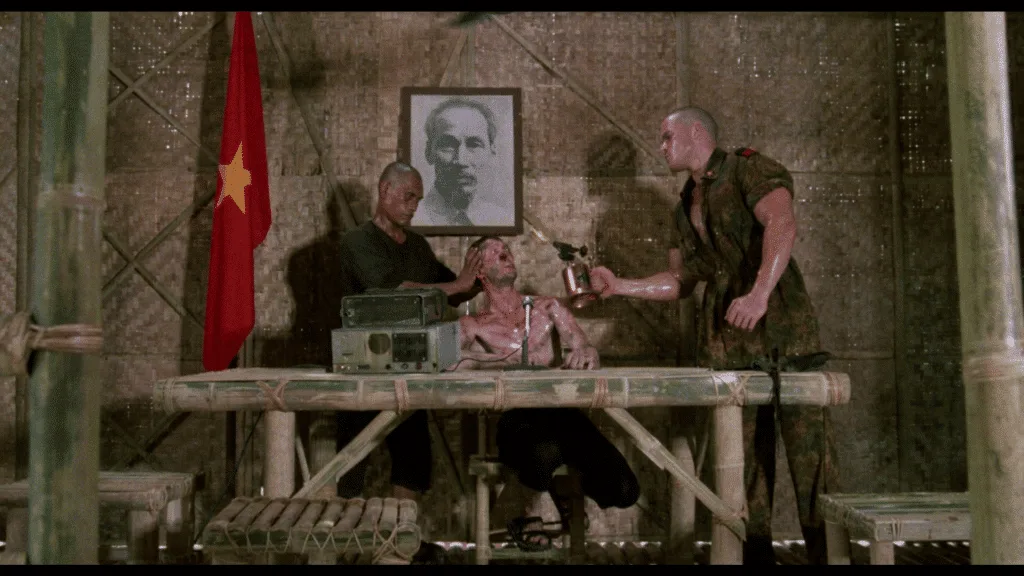

If Ransome is defined by his humanity, then, his Cold War opposite, Jakoda, is defined by his lack of humanity. Jakoda’s sadism is highlighted after Ransome has been taken captive by the NVA, who are working under direction of Jakoda and Olga. Ransome is thrown in a cell with another American captive, Martin Boomer (David Brass). Under duress, Boomer has been broadcasting anti-war statements intended to harm the morale of American troops (much like Margit Evelyn Newton’s character in The Last Hunter). (Cue stock footage of American soldiers in Vietnam, with Boomer’s broadcast laid over the visuals.)

Jakoda tortures Ransome, binding him to a rack and electrocuting him, in an attempt to persuade Ransome to agree to take Boomer’s place in the broadcasts. Ransome refuses, however; and one day, a badly-injured Boomer is returned to the cell he shares with Ransome. Boomer tells Ransome that he refused to read the lines given to him by Jakoda, and dies in the arms of Ransome. Jakoda’s response to this is to order the NVA guards to leave Boomer’s rotting corpse in the cell with Ransome (to place psychological strain on the Strike Commando who has already proven himself to be resistant to physical torture), something which appals even Olga, who calls Jakoda’s decision ‘inhuman’.

However, in the film’s final sequences, Jakoda is revealed to be nothing more than the pawn of the self-serving American Air Force Colonel Radek, the pair working together in Manila – in an import-export business (always coded in popular cinema as a front for espionage and subterfuge) – in the years following the Vietnam War. Where Rambo: First Blood, Part II goes to great lengths to establish how conflict with an internal nemesis (self-serving bureaucracy, represented by Charles Napier’s CIA field operative Marshall Murdock) can exacerbate conflict with an outside enemy (represented in the film by Steven Berkoff’s Russian officer, Lt Col Podovsky), Strike Commando conflates these two spheres of antagonism.

Fragasso was inspired to shoot a film in the Philippines by the actor Luciano Pigozzi (aka Alan Collins, who plays Le Due in the film), who had been living in the country for a while. (In fact, Pigozzi had appeared in a fairly small role in Margheriti’s Philippines-shot The Last Hunter.) Mattei’s other work in the Philippines includes the Miles O’Keefe-starring Double Target (Doppio bersaglio)in 1987; and Robowar (Robowar – Robot da guerra, 1988), an unholy mash-up of John McTiernan’s Predator (1987) and Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop (1987); Cop Game (Giochi di poliziotto, 1988), a pastiche of Christopher Crowe’s Saigon (aka Off Limits, 1988); Born to Fight (Nato per combattere, 1989); and, of course, Zombi 3 (1988), which Mattei completed for Fragasso after the original director, Lucio Fulci, left the production. On many of these films, including Strike Commando, Mattei shared directorial chores with his frequent producer/co-producer Claudio Fragasso, with a generally uncredited Rosella Drudi writing the script.

Fragasso engaged Mattei and Drudi to help construct the script for what would become Strike Commando. Fragasso and Mattei were credited as co-writers on the film (as ‘Vincent Dawn’ and ‘Clyde Anderson’, respectively), but according to the interview with Drudi on this disc, their input was limited to bouncing ideas around and, in the case of Mattei, telling Drudi to ‘borrow’ scenes from George P Cosmatos’ Rambo: First Blood, Part II (1985). (There’s even an off-hand nod to Stallone’s Rocky IV from 1985, when the American Ransome and the Russian Jakoda duke it out in an improvised boxing match towards the end of the picture.)

Mattei and Fragasso may have ‘borrowed’ ideas for scenes from Rambo: First Blood, Part II, but they lifted even more from Margheriti’s The Last Hunter, including recycling footage shot for that film alongside some very noticeable 8mm and 16mm stock newsreel footage. (The mixing of different film gauges is much more jarring in this HD presentation than on the old lo-fi videocassette releases with which most of this film’s fans, myself included, will be familiar.) Mattei’s use of stock footage is well-documented: his 1980 riff on Dawn of the Dead, Zombie Creeping Flesh (Virus), featured a good quarter hour of footage from Ide Akira’s 1974 ‘mondo’ documentary Nuova Guinea, l’isola dei cannibali, depicting wildlife in New Guinea and graphic funeral practices. In the interview with Fragasso on this disc, the producer / co-director notes that Mattei was an expert at film editing, and this is ‘why Strike Commando features so much footage from other movies’. (Mattei would reuse footage from Strike Commando, as well as other pictures, in Cop Game.)

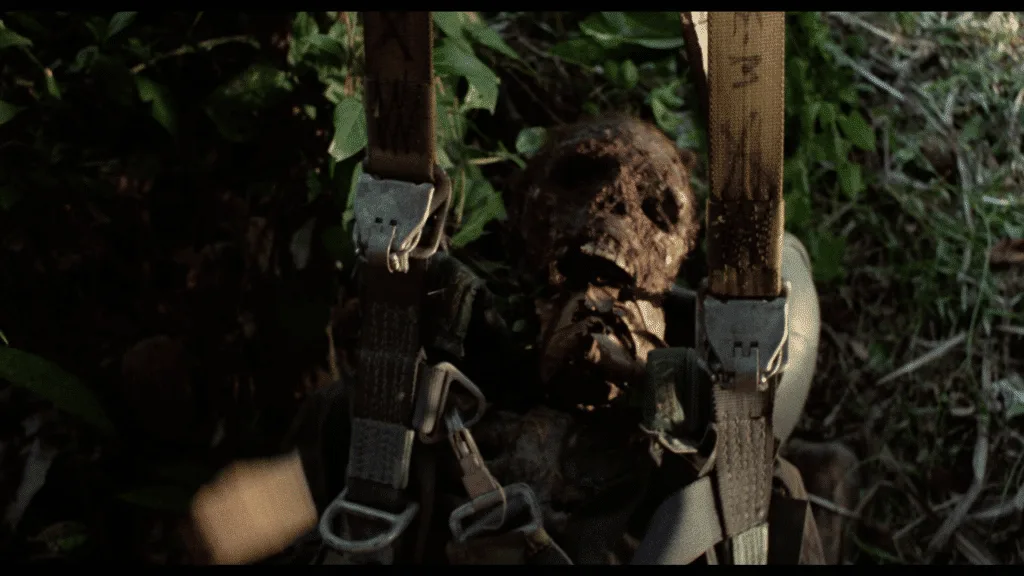

Even where footage isn’t directly culled from other sources, the staging of some scenes in Strike Commando is strikingly derivative. When Ransome and the South Vietnamese villagers are startled by the decaying corpse of an American helicopter pilot that falls from the treeline and hangs suspended by the straps of the parachute to which it is still attached, Strike Commando borrows its staging from a very similar sequence in The Last Hunter: in fact, the corpse looks remarkably similar to the rotting airman in Margheriti’s film, and one may wonder whether Mattei and Fragasso found and used the same dummy corpse.

Lead actor Reb Brown had previously played a somewhat similar role in the Vietnam War-set film Uncommon Valor (Ted Kotcheff, 1983) as ‘Blaster’, the demolitions expert. He had also worked with another Italian film director, Antonio Margheriti, on the 1983 sword-and-sorcery film Yor, the Hunter from the Future (Il mondo di Yor), and in the late 1980s would appear in a number of Italian exploitation films. In 1989, Brown would play another Vietnam War veteran in Lang Elliott’s Cage, in which he would act alongside Lou Ferrigno: Ferrigno had of course played another Marvel comic book character, the Incredible Hulk, in the television series that was contemporaneous with the television movies in which Brown played Captain America. Brown would go on to work with Mattei again, starring in Robowar, again written by Drudi and produced by Fragasso.

In the interview on this disc, Fragasso says that Strike Commando ‘sold like crazy’. Neither Strike Commando 2 (Strike Commando 2 – Trappola diabolica, 1988) nor Double Target ‘came close to repeating the original’s success’. Fragasso suggests that the commercial success of Strike Commando was because the film ‘had emotions’ that were articulated in the father-son relationship between Ransome and Lao, which Fragasso defines as ‘something intimately Italian’. The other films focused too heavily on action, he argues. English-speaking fans who encountered the film during the 1980s might disagree: the action was the heart of film, anchored by the artwork which depicted Ransome wielding a bizarre assault rifle with seven barrels, underslung grenade launcher and telescopic sight. (This was the artwork contained on the UK VHS release from Avatar, from which 46 seconds of a cockfight were cut by the BBFC before the film could be given an ‘18’ certificate for home video.) Nevertheless, though they could be dismissed as trite padding, the scenes featuring Lao and Ransome offer a moral perspective on the broader cultural differences between the two: Ransome promises Lao that he will one day take the boy to Disneyland where ‘They have popcorn and ice cream growing on trees’, and Lao reminds Ransome that ‘This is not your war’ – when it is finished, Ransome will return home and ‘we will have to stay here’.

Strike Commando goes full sentimental when Ransome returns to the combat zone to investigate the Russian presence in the region, and discovers that the South Vietnamese villagers who sheltered him have been slaughtered. Among the bodies is Lao, who is barely alive. ‘American, tell me again about Disneyland’, Lao whispers. Weeping, Ransome launches into an extended monologue: ‘They got tons of popcorn there. All you gotta do is climb the tree to go eat it [….] And there’s a genie, a magic genie, and he can’t wait to grant your wishes’. As Lao expires, Ransome lets out a howl of pain, an animalistic outburst that is equivalent to his scream of rage.

Severin Films’ release contains a superb interview with Rosella Drudi, the screenwriter whose frequent collaborations with Mattei and Fragasso during the 1980s were largely uncredited: in fact, the story and script for Strike Commando are credited to ‘Vincent Dawn’ and ‘Clyde Anderson’ – the Anglicised pseudonyms of Mattei and Fragasso, respectively. In reality, the pair contributed little to the actual writing of the film, according to Drudi: Mattei and Fragasso simply bounced ideas around the room, and Drudi crafted these into a coherent screenplay.

Drudi’s work on Mattei’s films is particularly interesting inasmuch as it appears to challenge gender stereotypes – at least, those Hollywood stereotypes that associate action and war films with the macho mindset. However, it’s worth noting that Italian cinema had plenty of precedent for this (in terms of female writers writing scripts for exploitation films): for example, in Elisa Briganti’s work with Lucio Fulci on Zombie Flesh Eaters (Zombi 2, 1979) and The House by the Cemetery (Quella villa accanto al cimitero, 1981), and Enzo G Castellari (1990: The Bronx Warriors / I guerreri del Bronx, 1982), among others.

Drudi says here that the suggestion women aren’t interested in war films or action films is rooted in chauvinism; as a long-term fan of war and action pictures, Drudi found the writing of Strike Commando to be a rewarding experience and describes it as ‘pretty normal for me. It was like writing any other movie’. Nevertheless, Mattei’s tendency to dictate that the script should contain so many elements lifted from Rambo frustrated Drudi, who wanted to write something a little more original. However, she conceded because of Mattei’s kindly nature: ‘He had that same, cynical attitude in the vein of legendary director Mario Monicelli’, she comments, referencing the director of oh-so-many examples of the commedia all’italiana (Italian-style comedy).

Severin Films’ Blu-ray release of Strike Commando is in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1, on a disc locked for region ‘A’ playback. The presentation, mastered in 2k from the original negative, is very good. Shot on 35mm, the film looks very handsome in this HD presentation. A pleasing level of detail is present throughout, and skintones are naturalistic. Contrast levels are solid throughout, with velvety blacks and a delineated curve into the toe. Highlights are evenly-balanced too. An organic level of film grain is present, though this sometimes feels ever-so-slightly muted, perhaps owing to the encode. There is some minor damage present, mostly in optically-printed sequences: for example, the film’s opening titles features some bold vertical lines. All of this damage is very minor, however, and is certainly organic. Projected onto a 100” screen, the presentation looks excellent and film-like, certainly far better than any other home video release Strike Commando has so far endured.

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 track in English and a LPCM 2.0 track in Italian. Both tracks are very good, with excellent range – other than the scenes exclusive to the extended cut (more on that below). Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided, though these are ‘dubtitles’ and based on the English-language dialogue. (The film appears to have been shot predominantly, if not exclusively, in English, so this isn’t too detrimental; but English subs for the Italian track would have been an added bonus.)

Two cuts of Strike Commando are contained on the disc: the theatrical cut, running for 91:45 minutes; and an extended cut, with a running time of 102:09 minutes.

The scenes exclusive to the extended cut are identifiable by a noticeable shift in the quality of the English-language audio track: the audio in these scenes is noticeably compressed – tinny and with some heavy clipping – and sounds as though it may have been sourced from a tape.

The scenes added to this extended cut include

- (i) a lengthier first encounter between Ransome, Le Due and Cho-Li, in which Le Due suggests that the discovery of the wounded American soldier ‘may well be the answer to our prayers’, but Cho-Li warns that Ransome’s presence may provoke a violent response from the Russians;

- (ii) a sequence set on board a US Navy destroyer, in which Harriman discusses the ‘impetuous, idiotic’ Radek with a General, and the General tells Harriman that Radek ‘has strong support in Washington’. The General suggests the dead members of the Strike Commando unit should receive posthumous medals, to which Radek responds angrily: ‘You don’t win wars with posthumous medals’;

- (iii) a scene following Sakoda’s killing of Le Due, in which Lao wonders where Le Due is, and suggests to Cho Li that Ransome ‘could be a big, strong husband for you’;

- (iv) a scene towards the end of the film, with Harriman visiting the General, stating that Radek is a spy for the KGB, and the General legitimising a strike against Radek, but acknowledging that Ransome will have no support and will be a ‘one-man show’.

As contextual material, Severin Films’ release includes the film’s trailer (2:05); ‘All Quiet on the Philippine Front’ (13:11), an interview with co-writer Rosella Drudi; ‘War Machine’ (19:44), an interview with Claudio Fragasso; and an in-production trailer (2:32) assembled to appeal to foreign distributors and showcasing some of the footage from the film.

In ‘All Quiet on the Philippine Front’, Drudi talks about the processes involved in scripting Strike Commando, and reflects at length on her work with Mattei and Fragasso. Drudi states that she was driven by the notion that ‘A hero must always succeed, and this is something current films have lost. There’s nothing better than walking tall heroes accomplishing what they set out for, never leaving their inner values behind’. As a screenwriter, Drudi’s approach was to streamline the narrative for the audience, ‘underlining the clear motivations of your hero and your villain right from the start’. She worried about creating a hero and villain that were too ‘toned down’ and accepted that the ‘cartoonish portrayal’ of the film’s principal antagonist (which she identifies as Jakoda, rather than Radek) was necessary. She reveals that she never visited the sets of the films Mattei madein the Philippines though was on set for many of his domestic productions.

Drudi says that Strike Commando was shot in 1985 but not released until significantly later; and on release, the film’s popularity exceeded her expectations. She credits the film’s balance of action and drama for this, as well as the ‘cartoonish’ villain and the moments of intentional excess that verge on self-parody. Drudi suggests that the budget looks in excess of what it really was, thanks to some of the visual effects, and the film overall is anchored by the presence of Reb Brown and his ‘fresh, sincere performance’ to playing Ransome.

In ‘War Machine’, Fragasso discusses the production of Strike Commando, revealing that the film was shot in Pagsanjan, one of the locations in which Coppola photographed Apocalypse Now. (Fragasso refers to Coppola as a ‘mediocre’ American director with an utter straight face: it’s hard to tell if he’s serious or joking.) Fragasso relates a number of amusing anecdotes from the production, including the revelation that he and Mattei were in a helicopter, provided by the authorities in the Philippines, and experienced turbulence, with Mattei quipping that he would die in a helicopter with Fragasso. (The same year that Strike Commando entered production, 1985, the actor Claudio Cassinelli was killed in a helicopter crash whilst filming Sergio Martino’s Hands of Steel / Vendetta dal futuro.) Fragasso also notes that Mattei was ‘a really lazy guy’ and refused to learn English to communicate with members of the cast and crew who didn’t speak Italian, and that Alex Vitale was ‘constantly exercising’ on the set, and this was worked into the film.

Both interviews take place in the editing suite for Fragasso’s film Karate Man, in post-production at the time the interviews were recorded.

Shorn of the all-too-sincere, preachy moralising of their Hollywood models (for example, Rambo: First Blood, Part II), Bruno Mattei’s films skirt on the edges of self-parody and, admittedly, many of them fall off it. They are probably best described as an acquired taste, and I am an unashamed fan of his films: in the college I used to teach at in the early 2000s, I pinned to the wall of my office a collage of posters from Mattei’s films with the caption ‘This office is a Bruno Mattei-friendly zone’, provoking much good-natured mocking from colleagues; and I went so far as to stage a mini-festival of Mattei’s films (including Zombie Creeping Flesh, Rats: Night of Terror, Shocking Dark and Robowar) using VHS tapes and the projector in the lecture theatre. That said, if you have ever wanted to watch a film in which a burly man stares down a cobra; or in which a cutaway to a US base of operations is underscored by an offscreen drill instructor referring to troops as ‘ruptured ducks’ or telling them to ‘stop swinging your butts: you’re soldiers, not hookers’; or, for that matter, in which the protagonist and antagonist go head to head, literally, by running at one another and butting foreheads like rutting stags… Strike Commando will hit your sweet spot. The film is a bag of cliches – from scenes of an elite, highly-trained commando walking, fully exposed to enemy fire, across open paddy fields with a platoon of rifle-carrying villagers, to running in slow-motion from mortar fire – but is nevertheless hugely entertaining.

Severin Films’ release of Strike Commando is excellent, containing a superb release of the film alongside some illuminating contextual material. For more details, please check out the Severin Films site.

[i] Brown had played the titular comic book character in the 1979 television movies Captain America and Captain America II: Death Too Soon.

[ii] Pick a verb. They all fit.