It’s no great surprise that the early relationship between Mary Shelley (née Godwin) and Percy Bysshe Shelley has proven irresistible to filmmakers, given its importance to the development of horror. Perhaps my favourite version of the events at the Villa Diodati comes via Ken Russell’s Gothic (1986), which presents a colourful, but nightmarish spin on those long rainy summer nights. There is something of Gothic in A Nightmare Wakes, at least in terms of its characters, setting and topic, and in how it encompasses imagined sequences alongside verifiable facts. However, it takes this same premise and explores it in quite a subtle, understated manner, with a carefully-constructed female perspective. It’s muted, very picturesque and uses low-key period details effectively, alongside the sparing use of chiaroscuro bad dreams. Mary is the focus, and as her situation feels ever more precarious and vulnerable, the film presents writing as her escape.

I suspect that this was, to an extent, true – though early 19th Century folk probably didn’t see the creative arts as a kind of self-help in the way which is current for us. We see the early days of the gathering at the Villa, with a small role for Byron and Polidori – but really the film follows Mary, Shelley, and – somewhat surprisingly given Byron’s small role, Claire Clairmont, Mary’s stepsister. We see Mary go through a gamut of miscarriage, cot death and romantic difficulties. True enough, Mary was less open to Shelley’s much-vaunted ideals of ‘free love’ and saw clearly enough how ill-supported she would be were she never to marry, a point the film makes, but the main thing to take away here is the sense of distance between the men and the women. Mary’s quiet agonies (she screams and rages mainly in her hallucinations) are presented alongside the playful, immediately-resilient behaviour of Shelley and his male friends, with Shelley getting over Mary’s late-term miscarriage almost immediately. Obviously, this is one of the film’s uses of artistic license, and it’d be wrong to suggest that Shelley was completely unaffected by all of this; Mary did say in her journals, though, that she found the impact of pregnancy and miscarriage absolutely draining, and therefore this emphasis does chime with the focus which the screenplay has chosen.

We do get something of the writing competition which helped to produce Polidori’s novella The Vampyre and Mary Shelley’s first novel, but it soon becomes clear that only Mary is really making any progress – and always against the backdrop of a philandering partner and a thirsty stepsister, one of whom envies her writing prowess and one of whom envies her family dynamic – patchy as it seemingly is. As Mary begins to struggle with her feelings of abandonment, some of the symbolism in some of the sequences is pretty straightforward; that said, the film does a good job generally at playing on the content of Mary’s journals and the descriptions of her nightmares, bringing them to bear on her attempts to hold her home life together as she writes her novel.

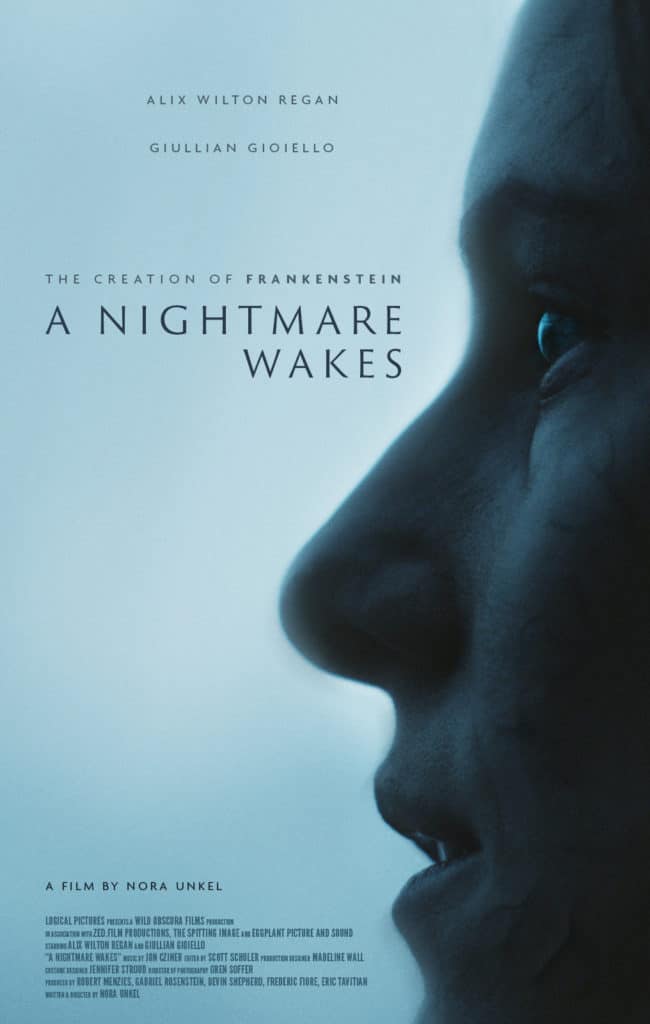

Unusually, Shelley is presented here as a deliberately stymying influence on Mary and her writing; that’s a new development, but it takes the narrative in some interesting places, even if the divide between dream and real life isn’t always fully clear. The way in which Mary’s imagination begins to link Shelley with Victor Frankenstein is inspired; there isn’t a mass of script in this film, but what is there is a good fit, economical, without simply leaving a void. The performances are very good too: one quibble is that the actress playing Mary is rather older than Mary would have been (Mary was eighteen when she started the book; actor Alix Wilton Regan is thirty-five) but, look, it would be tough to find an eighteen year old to pull off this role, and Wilton Regan is very compelling and sympathetic here, easily carrying the largest share of the screen time. Giullian Yao Gioello as Shelley, and Claire Glassford as Claire Clairmont are themselves excellent in their roles.

Ultimately, this is a film for people who already have some interest in the origins of Frankenstein, and by the same token, people who do have that interest may have a few misgivings with some of the artistic license taken by director and writer Nora Unkel. All in all, though, this is a worthwhile snapshot of that period, a visually-appealing film which is both sensitive and ambitious enough to present something engaging. It’s a thoughtful historical drama which successfully sees its own perspective through to the end.

A Nightmare Wakes comes to Shudder on Thursday, February 4th 2021.