American Psycho (1991), third novel of self-styled enfant terrible Bret Easton Ellis, was one of those books whose notoriety preceded it and swept it along. Becoming a kind of double-dare-you read in the same way that many films have become rites of passage, it no doubt found a sizable audience that quite simply wanted to experience its shocks first-hand. Alongside its feted brutality, it was also a novel which had acquired the rep for being ‘unadaptable’ for film – too busy, too repetitive, too grotesque. However, it turns out it could make a good film, thanks to the hard work of director Mary Harron and co-writer Guinevere Turner – who transformed the novel and, along the way, vastly improved it.

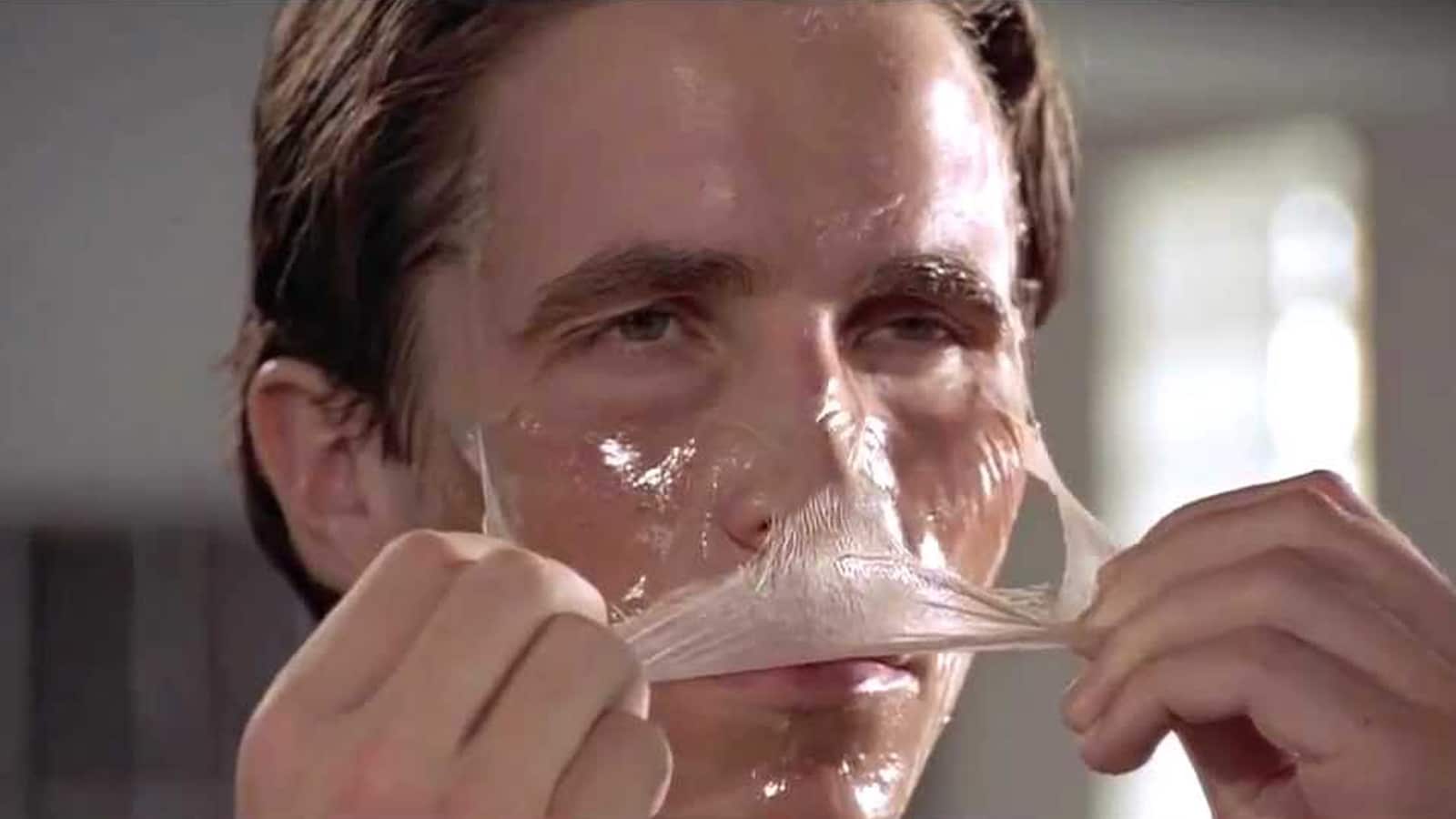

By focusing closely on the character of Bateman himself, they were able to refine the novel’s key, if sprawling emphasis on the cavalier lifestyles of the Wall Street wealthy in the 1980s. Bateman becomes a kind of yuppie Everyman, a scion for his ‘kind’, but whilst we’re invited to witness the array of petty obsessions and easy money which surrounds him, he remains an aloof, unknowable character – perhaps, as Bateman (Christian Bale) himself suggests, he ‘simply is not there’. It is this non-person status which, for me, is the bedrock of the film’s true horror. Bateman represents everyone around him, but he is no one. He openly recognises this, and the film’s initial rising tension stems from his early acknowledgement of, and exploitation of this anonymous state. Bateman artfully flits from one identity to another, committing (or fantasising) his worst crimes under the names of other people. This cannot be sustained forever, though, and by the end of the film, his missing identity is the source of his greatest, inescapable misery. In effect, his character has travelled no distance, and his rebellion has been an appalling fantasy.

The world which Patrick Bateman inhabits is a strange one, and the film takes pains to showcase its odd fixations and competitiveness. This competitiveness is not based on the usual things: doing well at work, showing due diligence, putting in the hours. It’s made abundantly clear, by Bateman’s early feet-on-desk work pose, that a work ethic is not part of the deal here. What seems more important – beyond the sheer luck which seems to bestow prestigious accounts on one man and not on another – is the display of doing well: you play the game by looking the part, wearing the right suits and being able to book the right tables at the best restaurants. In one of the film’s finest comic elements, a restaurant called Dorsia attains Waiting for Godot-levels of significance – the place everyone wants to go to but, at least within the confines of the film’s narrative, never does. That is, except for a suit named Paul Allen (Jared Leto). Well, so he says. For Bateman, Allen is the embodiment of ‘making it’. He can get a table at Dorsia. That’s it. Add to that his handling of a sought-after account and Bateman’s enmity knows no bounds.

“The world just opens up and swallows them…”

It is in this Mecca of disaffected and wealthy men that Bateman develops a plan. When Allen mistakes Bateman for yet another financial sector worker called Marcus Halberstam – which, as Bateman admits, is a pretty easy mistake to make – Bateman decides to keep up the ruse. Answering Allen as if he were Halberstam, Bateman decides to use this as an opportunity, committing a crime under this false name and making damn sure that Allen believes that he is Halberstam, reinforcing it time and again before taking an axe to the competition, citing Allen’s friendly terms with the Dorsia as he does so. To complete the display, Bateman lets himself into Allen’s apartment, fakes a trip to London (no one apparently recognising his voice when he impersonates Allen on his answerphone) and then, when the disappearance is investigated, Bateman doubles down on his rootlessness, his forgettability. Had he seen Allen? He’s not sure, as he explains to Detective Kimball (Willem Dafoe). He evades his questions by listing names and venues, possible sightings, and giving obfuscation after obfuscation: in effect, he uses his lifestyle as a shield, and Kimball is not able to get past it in any meaningful way. So far, so good.

With Allen out of the picture, Bateman is free to colonise his identity, too. On one hand, this furthers his assertion that Paul Allen is still alive and well and still ‘part of that Yale thing’; on the other hand, it shows Bateman having fun with his non-persona, able to commit acts of aggression and sexual violence under another new name – Paul Allen’s. Reinforcing his new persona of Paul Allen by carefully repeating his name to anyone he needs to listen, Bateman hoodwinks a young prostitute – herself given a fake name for the proceedings which follow – and harms her with impunity, now treating what had been expedient as personal entertainment. At this stage in the film, ‘Patrick Bateman’ is liberating as it is simply a tabula rasa, ready to adapt and adopt whatever useful identity comes his way. With this new agency and awareness of what can be done, Bateman’s crimes escalate rapidly. Interestingly, it is only the women in his life who seem to really see him as Patrick Bateman; his closest friends throw wisecracks at him, but seem to not see even his most self-evident crises. Evelyn, his fiancée (Reese Witherspoon) and Courtney, his lover (Samantha Mathis) always address him personally, which is a step above other interactions he has, even if they, too, are part and parcel of an anonymous web of people who value women even less than men. But at the points in the narrative where they appear and seem to care, Bateman is in the ascendant. He doesn’t want to know. He doesn’t want to be tied down, and certainly doesn’t want to be tied down to his own identity in any quantifiable way.

“I’m not here…”

Little by little, however, Bateman’s agency is eroded by inconvenient encounters with real life. Kimball’s attentions are key here: not only do his questions force Bateman to address the quantifiable – the dates, the times which attach to the names and the venues – but they reveal something else entirely. In effect, the certainties which Bateman was willing to hang on to are not certainties at all. Kimball points out that, on a contested date which Bateman believed required an alibi, he already had one. He was with Paul Allen. Was he? This may or may not be correct, but the initial relief Bateman feels when it seems he is, finally, off the hook, quickly turns into a raging disappointment. His rootlessness is now the province of others, allotted by them, and as such controlled by them. It now becomes his priority to reclaim his own identity, which, now that it is being doled out by other people, feels less and less like it truly belongs to him. When he visits Paul Allen’s apartment to check on the place – which he has apparently been using as a dumping ground for bodies – it is pristine, redecorated and waiting for a new owner. He tries and fails to masquerade as an interested party with an appointment to look over the place, but the realtor in attendance is unconvinced. Bateman’s powers of disguise are on the wane.

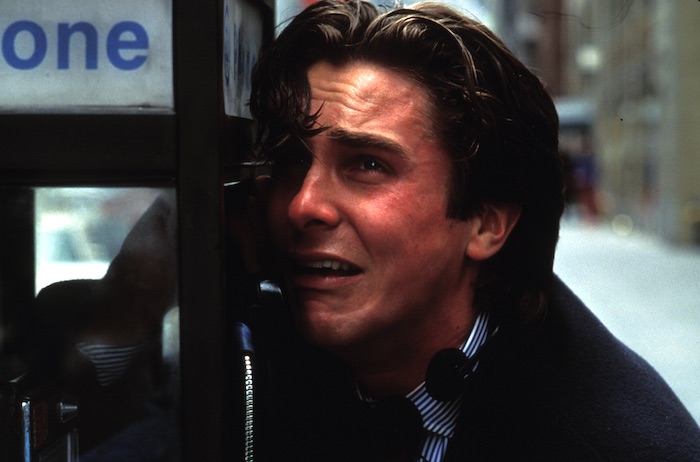

As the film’s final acts of ultraviolence take place, we see a Patrick Bateman now desperate to get caught – as Patrick Bateman. After a final killing spree he runs away at first, presumably by impulse, but almost immediately he decides to take the credit for the crimes – as shown in that tragicomic late night phonecall to his lawyer. Now, he names himself over and over. He finally feels that it’s time to claim ownership, but not only that; he seems to crave a way out of the lifestyle which has now shown that it’s bigger than him, even dwarfs him. Desperate, he confesses to the killings, leaving nothing out (other than where his memory is challenged) and, by all accounts, he seems to expect a way out. He heads out to lunch the following day, and is relieved to see his lawyer is there. Expectantly, he approaches him.

In a supreme moment of irony, Bateman’s escape is denied; it is denied on the same grounds which Bateman earlier exploited to his benefit. His lawyer doesn’t recognise him, and thinks he is someone else, ‘Davis’; he thanks him for the phone prank, but tells him there was one glaring error in the joke: Patrick Bateman would never, ever do something so outlandish. He is “such a boring, spineless lightweight.” Angry and frustrated, Bateman tries to convince him that it wasn’t all a joke and that he is, in fact, Pat Bateman. This is never acknowledged or accepted; instead, still addressing him as Davis, Carnes tells him that the joke is no longer funny anymore. As for his assertions about killing Paul Allen? Impossible. He had dinner with him just ten days previously.

“Something illusory…”

Did he? Who really knows. American Psycho swarms with names, interchangeable people who seem to have no remarkable features or identities. Not for nothing does the film make much of the business cards which, to an untrained eye, all look largely identical. The names embossed on the cards may differ, but for all intents and purposes, the cards display how identikit each of these men are. Bateman, realising this, at first takes advantage of the liberty this affords. If no one knows him, then he can be anyone, and he can indulge his darkest fantasies accordingly. And yet, this isn’t a true escape either: it’s only fun when he seems to be in control. Once he comes to crave that old anchor point of self, he sees – too late – that he is as much a victim of his anonymity as he is empowered by it. Having no real internal life, the ‘abstraction’ that is Patrick Bateman will never really be able to creep out of his two-dimensional existence. Whilst it’s a story which takes place before the internet age, there’s certainly something recognisable in our modern ability to design online personae which may seem liberating but, ultimately, allow perishingly few people to make real changes. Bateman seeks escape; this eludes him. It’s an existential nightmare, one where – pleasingly – the film returns to the book to show us its infamous final line, on the wall behind Bateman as he finds he has to rejoin the group, despite his best efforts: ‘this is not an exit’. This confession has meant nothing.