Between 1959 and 1984, thousands of ethnic Koreans born in Japan were offered the chance to resettle in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea under a grand cross-government migration scheme supported by the Red Cross Societies of both countries, and the International Red Cross. A benign-sounding Japan-based organisation, the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (‘Chongryon’), promoted the scheme, painting the DPRK as a land of opportunity compared to the post-war shambles of Japan, where descendants of ethnic Koreans were commonly both poor and discriminated against in wider Japanese society. Chongryon, as it turned out, was a Pyongyang-controlled propaganda front. The ironically-named ‘Paradise on Earth’ migration scheme proved to be anything but a chance to build better lives for the thousands of Japanese ethnic Koreans who, lured in by promises of a socialist heaven on earth, instantly encountered a hell in which not only were conditions exponentially more deprived than those they had left behind in Japan, but where every single aspect of their lives was subject to state control and paranoid political scrutiny. Encouraged by two self-interested governments and a large NGO, they had simply walked into a trap it was impossible to free themselves from, as once inside North Korea, they were forbidden to ever leave again.

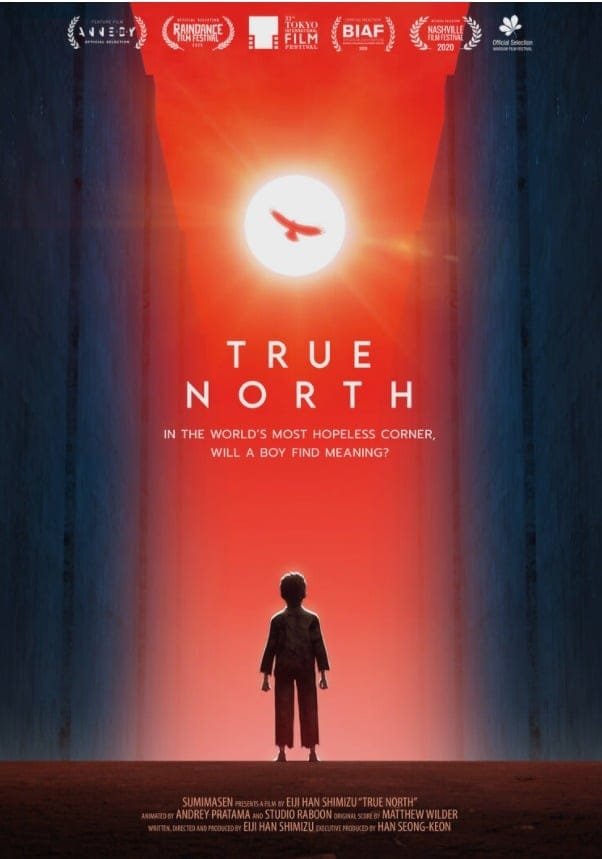

Eiji Han Shimizu, the creator and writer of True North, a full-length animated film centred around the horrors of the DPRK’s concentration camps, is a descendant of Japanese ethnic Koreans who ignored Chongryon’s call and the Red Cross’s ‘help’ and stayed put on Japanese soil. Shimizu, whose sole previous work comprises a documentary exploring the concept of happiness (2012’s ‘Happy’), based True North’s narrative on the testimonies of 30 defectors, survivors and witnesses to the abuses and depredations of the North Korean regime and its notorious labour camps. The film appears to be inspired by a need to bring survivors’ testimonies to life, and a chilling recognition that had his grandparents or parents made different choices, Shimizu himself could have numbered among the victims.

So. Not exactly a fun night’s viewing, you’d imagine. You’d be right. There’s plenty of viscerally harrowing content here, that even in semi-cutesy 3D animated form, is very hard to take in places. Shimizu’s film minutely depicts the structure and workings of the labour camp which his protagonist, nine-year-old Yo-Han, is despatched without trial alongside his kind-to-the-bone mother and sweet-natured younger sister, after their father is disappeared by the state for plotting to escape the country. The physical conditions they are expected to endure are shocking. Through young Yo-Han’s eyes we see the casual heartlessness and violence of the guards towards both young and elderly, the fatal diseases caused by vitamin deficiency from the slop diet they are fed, the ongoing risk of rape for female inmates (and execution for being ‘a whore’ if one is unlucky enough to become pregnant), and the brutal treatment of dissenters. We also witness the political ‘struggle sessions’, where prisoners are supposed to confess their anti-revolutionary sins and earn punishment, and point the finger at others to earn rewards and extra rations, ensuring an endless succession of betrayals and false accusations, usefully seeding mistrust between inmates. There’s also the fear of even worse things hanging over them at all times – the basement torture centre and the ominous-sounding ‘Total Control Zone’ whose exact nature is obfuscated until the very end of film, but the threat of which is enough to reduce hardened inmates inured to camp life to pleading, terrified messes.

Yo-Han, consigned to the camp’s coal mine, learns the rules and ropes of the place, and as he grows into adolescence and adulthood, rejects the example of his mother who manages to retain her sense of humanity, and starts to operate in an entirely self-interested way concerned only with his own survival. He hoards food and refuses to share with those who desperately need it. He spares no kindness or thought for the suffering of anyone outside his family circle. He snitches when it benefits him. It’s only when one of his casual betrayals starts a sequence of events that ends in family tragedy that he is forced to re-evaluate himself and how life in the camp has dehumanised him. It’s at this point the film takes on a wider theme – that of finding purpose and meaning in life when the conditions one is placed in denies nearly all personal agency and choice. Yo-Han, harkening back to the example of his mother, does find a way, however, and starts along a path of self-sacrifice and redemption combined with his camp survival smarts that in the end will save lives, lighten the load of a few more, and finally reveal the nature of the Total Control Zone.

True North, for all its upsetting content, remains an engaging story that surprisingly offers a few moments of uplift amongst a deluge of torment and darkness. Yo-Han’s psychological journey is compelling. In some ways it’s a coming-of-age story as much as an important depiction of historical and current abuses within the North Korean prison camp system, as Yo-Han and his friends decide what influences and ideals they will allow to shape them and decide their personal course as adults, no matter their surroundings. It’s also yet another portrayal of the banality of evil. There’s a lot to ponder in a wider philosophical sense.

While True North has plenty to tell the world about a particular set of horrendous injustices, it also compels the viewer to consider what makes life personally meaningful in less than ideal circumstances, and what can constitute rebellion when one’s life is controlled so exactingly from above under threat of violence and worse. Is it our friendships, service to others, or the ability to find fleeting moments of joy and beauty in the grimmest surroundings? A refusal to become what our captors would like us to be, and to mentally reject ideological demands and to risk thinking freely? In a world where the walls have been incrementally closing in on us over the past nine months and personal freedoms slowly eroded or corralled, these are questions well worth asking.