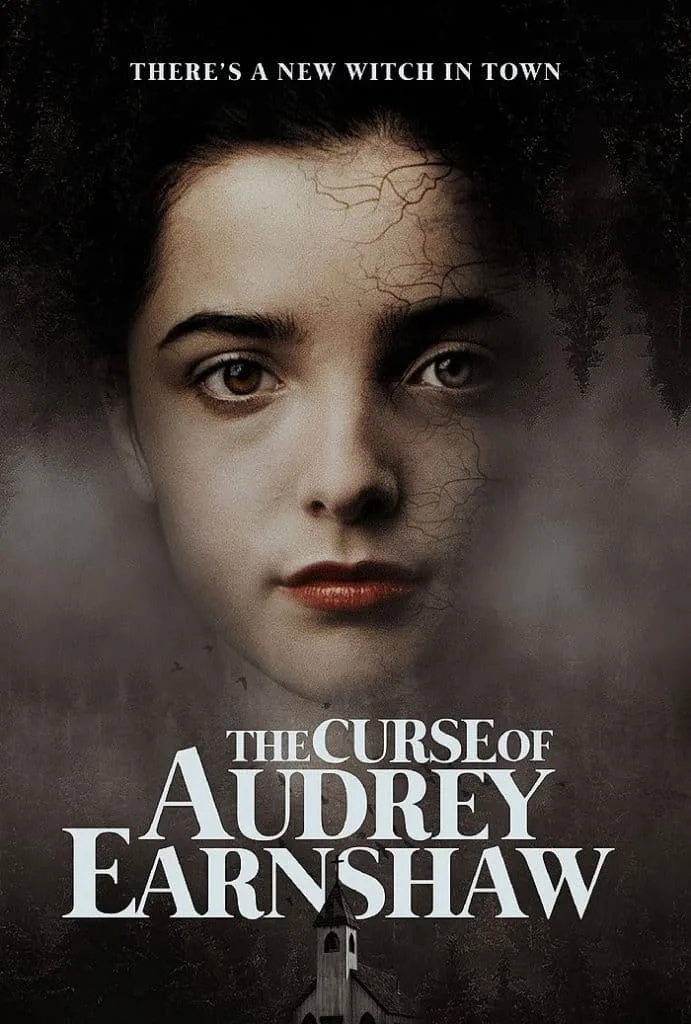

A curious set-up introduces us to The Curse of Audrey Earnshaw: is it a period piece? It certainly looks like one, but the on-screen text explains that, although the Irish colony appearing in the film arrived in the US in 1873, they have remained isolated from the modernising world outside – through the Fifties, when an ‘eclipse’ was linked to the spread of a strange plague which decimated human and agricultural life alike. That is, with the exception of one woman, Agatha Earnshaw, who gave birth to a daughter during this catastrophe. Whilst her farm alone prospered, she kept her daughter’s existence secret, distrustful of the small community on her doorstep.

Scoot forward to 1973. Audrey is now seventeen, and her mother has continued to keep her hidden – telling the girl that the townsfolk wish her harm. When a near neighbour arrives, desperate and hoping to sell some goods to support his own family, Agatha is having none of it, and Audrey – believing what she has been told – hides away, although seems incredulous afterwards that the man in question was a genuine threat. Still, shortly thereafter when Agatha (with Audrey concealed in her wagon) accidentally crashes a local child’s funeral with a heaving cartful of fresh produce, it’s perhaps understandable that the grieving father confronts her, albeit hitting her in the face. Audrey sees enough and is appalled – these people might just be as bad as mother said they were (though to be fair, rolling a tonne of food past a starving, grieving funeral party – and god knows where this hermit-woman is going with it – is a bit of an awkward faux pas, and it’s odd that this sensitive young girl kinda misses that point, whatever else takes place).

We’re soon afterwards shown proof that Agatha and Audrey are estranged from the local community for more than mother’s social missteps. They’re shown taking part in some sort of ritual, with people who don’t seem to be the same townsfolk we’ve already encountered. Afterwards, Audrey awakens outside on the ground, alone: it’s not clear how much she understands of what’s happened to her or why, but it seems to signal a shift in her behaviour.

She speaks to one of the cabal later, asserting her desire to hex Colm Dwyer, the bereaved father who assaulted Agatha; she takes a risk by finally being seen by another of the townsfolk but regardless, makes it her business to get into Colm’s house, posing as a fainting maiden on his property before stealing an item and using it to curse Colm’s wife (rather than him directly – there’s no justice or balance in the magic unleashed here). Malignancy soon plagues an already-devastated town, with death and madness on the rise. Audrey, whose abilities certainly seem good to go, tells her mother that she’s ‘ready’. Great timing, seeing as word of her existence is now travelling around the town. A collision course is set.

There are good elements in The Curse (or in some versions, The Ballad) of Audrey Earnshaw, but there are some odd stylistic and narrative choices too which hamstring the film in key respects. This is a shame. For starters, the unnecessarily complex narrative frame, whereby we have an Amish-like isolated community of Irish people – for some reason living in the days of grindhouse – seems a wholly odd choice. The 1970s setting here is largely, almost completely irrelevant; if there was meant to be any sort of conflict between old and new, traditional and modern, then it is blink-and-miss-it here. For all intents and purposes, this is 19th Century Ireland – it looks like such, operates as such and stays as such, excepting some tiny hints in the dialogue about ‘science’ out in the world somewhere and one rather detached scene at the end. Perhaps this is one of those attempts to render the film timeless, as other independent films have taken to doing by opting for analogue tech and so on, but this always feels to me like taking a lot of trouble to achieve very little. There are other visual elements which break the spell: the ‘starving community’ who all look incredibly healthy and well-fed; the presence of blindingly-obvious cosmetic fillers on a woman who has ostensibly lived her life beyond the reach of a beautician. I could also gladly bin the chapters; films being carved into fairly arbitrary chunks with a big piece of on-screen text to tell us what they’re called is another trend which interferes with the storytelling.

So there are issues here, many of which are born of idling down the path which so many other filmmakers have taken – a mistake, maybe due to the fact that this is a first feature. But likewise, this is a beautifully-shot film, which for the most part sustains a watchable amount of ambiguity: is this witchcraft? Or the paranoia and misfortune of a remote group of people pushed beyond duress? The film thrives most when it isn’t giving the answer. There’s an oppressive atmosphere, sometimes to the point of discomfort, and the small cast are given a great deal to do which, by and large, they achieve against an attractive backdrop and evocative landscapes.

To me, there are several clear parallels to The Witch in this film, 70s frame or not; the main difference is that the exiles from the larger community are the ones who prosper – at first, anyway. Otherwise, the bleak agrarian landscape refracted through natural light, the fear of witchcraft, the inefficacy of Christian faith, the presence of the old world in the New World and the way in which the story is centred on an adolescent girl all took me back to Robert Eggers’ vision of 2015. The Curse of Audrey Earnshaw is not dreadful by any means, but it misfires based on its at-times baffling decisions and derivative aspects, particularly when these call to a minor classic which avoided same.

The Curse of Audrey Earnshaw screens in limited theatres from 2nd October and is released on VOD on the 6th October 2020.