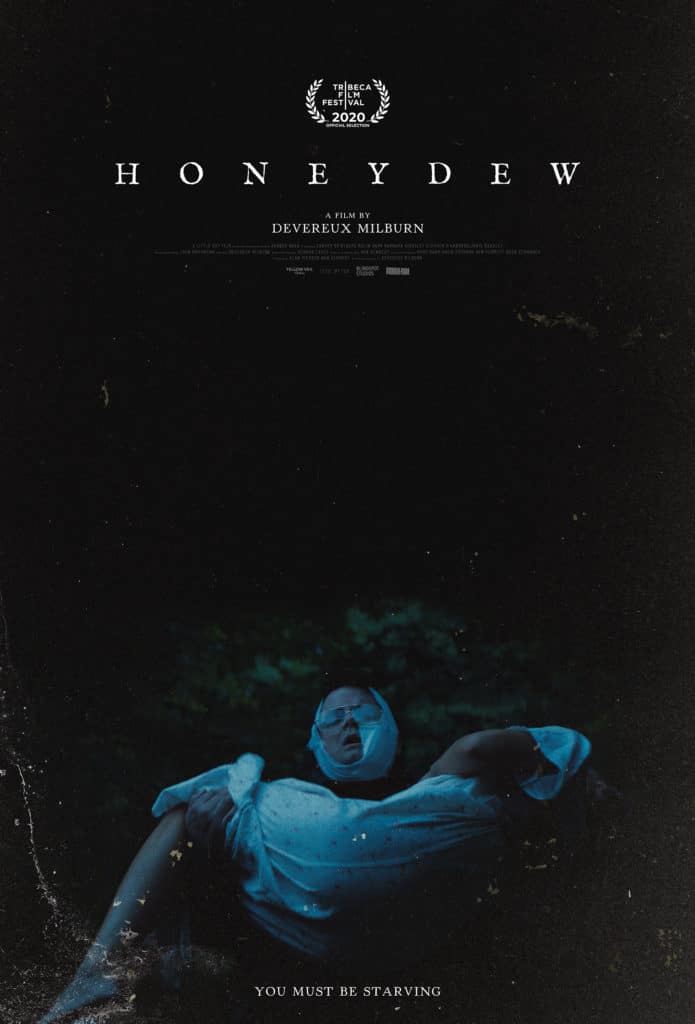

Honeydew is a film which represents certain challenges for a reviewer: this is because to describe anything of its plot – in a linear kind of way – would very likely be to misrepresent the vibe and style of the film. On paper, it fits quite neatly in the category of ‘backwoods horror’ which reminds us that, off the beaten path, things can go hideously awry for outsiders. So far, so familiar. However, the journey taken by the film along the way is anything but straightforward. One of its singular successes is in how ‘off’ the narrative feels, right from the beginning. This is a compliment, considering this was clearly the intention; the unsettling, unsettled feel is well sustained, too, and it’s the factor which really distinguishes the film from others in the subgenre with – let’s face it – largely similar plot trajectories.

We begin with a couple which seems anything but happy, rather like the marrieds in Koko-di Koko-da (2019). Rylie (Malin Barr) and boyfriend Sam (Sawyer Spielberg and yes, he’s a relation) are headed out into farm country for the purposes of research; Rylie is not – as her first scene suggests – just someone given to watching very unusual YouTube clips, she’s a doctorate student specialising in botany. More specifically, she is researching the impact of Sorghum, a fungal wheat infection which can cause damage to crops and toxicity in the crops themselves, harmful if consumed by livestock or humans. Sam is along for the ride as her assistant, but as a wannabe actor, he spends more time practicing his lines than he does speaking to his girlfriend. Already at this point, the rather obtuse relationship between them feels rather unnerving; a relationship breakdown feels like it’s hovering in the air. Spielberg does a good job in making Sam come across as hideously self-involved; the atmosphere is very strained, and Rylie isn’t a hell of a lot better. Matters don’t improve when they decide to camp overnight, and the farmer whose land they’re on tells them they need to find somewhere else. Feeling that they don’t have a lot of choice, they pack up.

Things veer a little into trope as we then run through the whole car trouble/phone trouble shtick, but the pair decide to enquire at a nearby house whether they can use their phone. The lady, called Karen (Barbara Kingsley), who eventually answers the door is pleasant enough but a little – distracted somehow. She invites them in and immediately sets about making them something to eat, and she introduces them to her non-verbal adult son Gunni too. Normal conversation is not a feature here. It’s interesting that Barbara Kingsley had a role in David Lynch’s most linear and accessible film The Straight Story (1999), as here’s a film which seems to be trying to out-Lynch Lynch in terms of aesthetics and tone. Everything feels wrong somehow, the house trapped in an earlier decade and so rammed with analogue tech, that this begins to feel like a character in its own right, something to placate the inmates of the house with its sheer archaic weirdness. Popeye keeps up a continual hum in the background of this film – you may never think of old cartoons in the same way. But, more specifically, the food and drink Sam and Rylie are offered seems to affect them somehow. Sam in particular – perhaps understandable given his low-cholesterol diet of recent weeks – can’t get enough of it, and seems to adapt quite readily to Karen’s warped hospitality, even sneaking around the house to eat some more. I hope I’m not spoilering to affirm that things go from odd to odder for these unwitting guests, though with food as a kind of weird intermediary, for reasons which become (somewhat) clearer.

Honeydew shows us some of its cards very early on by mentioning the impact of ergot poisoning on the psyche; it maintains this uneasy, queasy atmosphere throughout, doing a good job of crafting something hallucinatory – something which isn’t easy, and is aimed at and missed by many indie filmmakers. By using very rapid cuts, giving the feeling that we are only granted a few tantalising seconds with our characters before being thrown into a new scene, the film makes the audience feel as out of the loop as the characters must feel. There are other aspects which contribute to this: the limited dialogue, the sound-layering, that overwhelming soundtrack which combines choral elements with the ominous sound of metal being drawn across metal, like blades being sharpened. This, wrapping around a disjointed story about two dubiously-connected characters, enables us to immerse ourselves in this world, and the pay-off, whilst not hyper-gory, is a suitably unseemly way to draw things to a close. If the denouement isn’t a million miles away from the likes of American Gothic (1987) with its own, crazed, isolated family unit (and of course there are many, many others) then we can still certainly say that Honeydew’s crowning glory is in its atmosphere. It crowds the senses, in a compelling, unsavoury and very sinister way.

Honeydew (2020) screened at the Celluloid Screams Horror Festival in Sheffield, England.