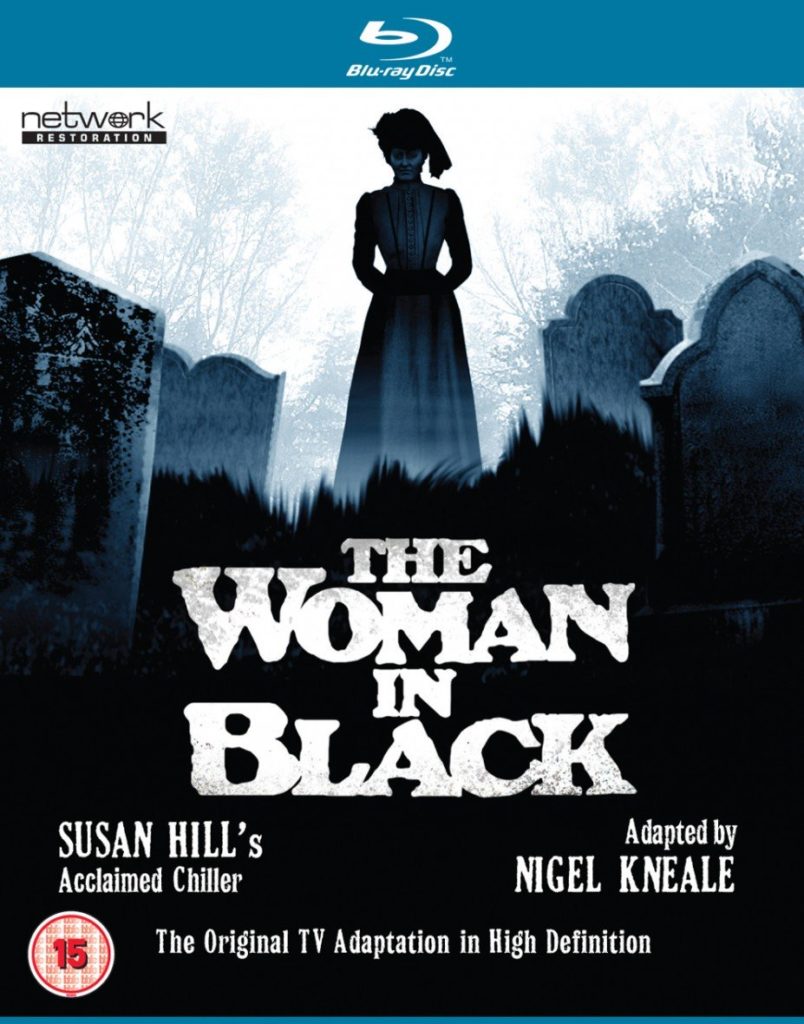

Screenplay writer Nigel Kneale has a superb pedigree as a purveyor of the strange and the supernatural. Never is this made clearer than in his adaptation of the 1983 Susan Hill novella The Woman in Black. In fact, even mention this TV film to fans of a certain age and/or persuasion, and they will immediately enthuse about its impact on them, often particularly that scene. Perhaps many others are more familiar with this story via the 2012 rendition directed by Eden Lake’s James Watkins; with regards to the latter, I’m determined not to simply poke holes here in what is an overall entertaining period horror, but Kneale’s version has held its ground simply because it excels as a piece of terrifying tale-telling.

Arthur Kidd (one of those odd minor alterations from the novella, where he is ‘Kipps’) is a young solicitor at a London firm. He’s given the responsibility – as a means of compelling him to take his trade more seriously – of clearing up some of the necessary arrangements following the death of a long-term client, Mrs Drablow. He makes the journey to Crythin Gifford, a remote town on the East coast of England, though at first he meets a guarded response from the locals he meets when he mentions his business there. Nonetheless, he attends Mrs. Drablow’s sparse funeral, noting only one other mourner – a woman dressed in the kind of high mourning which belongs to a generation before. She’s not mentioned by any of the others present at first, though when associate Mr. Pepperell seems to see her, he reacts with alarm.

Arthur soon afterwards needs to visit Mrs Drablow’s former residence, Eel Marsh House – it’s a dour old pile, cut off from the rest of town by a winding causeway which is submerged twice daily by the tides. He soon begins to appreciate the reticence of the locals for the place. The strange woman reappears outside, radiating a kind of menace which terrifies him back indoors, whilst a range of strange, horrifying phenomena soon begin to impact upon his work. Gradually, he begins to make sense of a local tragedy – one which begins to ensnare him.

This really is a masterclass in storycraft. An understanding of subtlety is manifest throughout, with a slow, deliberate escalation of the otherworldly which needs no flashy scares. Different kinds of scares depend on different kinds of responses: the most simple affect your reflexes by making you jump, but the most memorable are those which play on the imagination – making you doubt, look twice, or shrink away from what’s on screen. The horror here is doled out carefully; the development of something truly ghastly happens almost gently, with as much happening off-screen as on it. You do not need to see children jumping to their deaths – the small revelation of something profoundly amiss in the churchyard is singularly effective in exploring the same plot point.

Whilst you could raise an eyebrow at some of the depictions of class in this – Kneale has some form for representing the working classes as somewhere between fear-inducing and inept – there’s perhaps more to get to grips with in the nature of the larger tale, presented here as something akin to a medieval witch legend where hell has no fury like a woman scorned and curses extend beyond the grave. It would be possible to see this through a gender lens (which itself links back to class) in its examination of gendered stigma and monstrous motherhood, but for me the backbone of the curse itself isn’t as intriguing as its manifestation. This is no morality play where bad people get their comeuppance; Jennet’s fury consumes anyone who gets near. Here, where Arthur Kidd (Adrian Rawlins) is represented as a loving father and a conscientious man, it makes his involvement with the Woman in Black all the more galling. It reminds me somewhat of Ring, the Japanese film made a decade later – similarly there, the drowned girl Sadako’s vengeance destroys everyone, even those trying to help put her to rest. Another similarity between these two films, and with many other stellar horror tales, is the fact that the monster is barely on screen at all. In The Woman in Black, it adds to the pure shock of certain scenes (and yes, we’re back to that scene again).

Those who already love this film will certainly value this high-quality version of it. It looks excellent, with crisp colours and lines throughout; the ‘ad break’ screens are included, and I’m on the fence with this, though for nostalgists it’s probably a positive (and these bookend some of the tensest moments, for people who want the relief of a short moment’s pause). There are extras available on this release in the form of an audio commentary (Mark Gatiss, star Andy Nyman and Kim Newman), an image gallery and a collectable booklet written by Andrew Pixley. For those who are maybe more familiar with the newer film or the stageplay, then this Blu-ray is testament to a way of telling ghost stories on-screen which has been largely set aside; it has lost nothing over the years, and it still has the power to make your skin crawl.

The Woman in Black will be released by Network on 10th August 2020. For further details, please click here.