The notion of the ‘cursed film’ is nothing new in horror cinema, and it has formed the basis of some deeply disturbing, evocative projects over the course of the years. The Ring was a hugely successful crossover from what was, for many viewers, a largely unknown horror tradition with its own mythology and rules of operation, but even without an understanding of Japan’s fantastical relationship with the seas which surround it, the curse of Sadako still made hideous sense. More recently, the Masters of Horror television series offered us an episode called Cigarette Burns, taking for its central premise the idea of a mysterious, dangerous film which endangers its audiences via its very being, even causing cinemas to burst into flames upon screening.

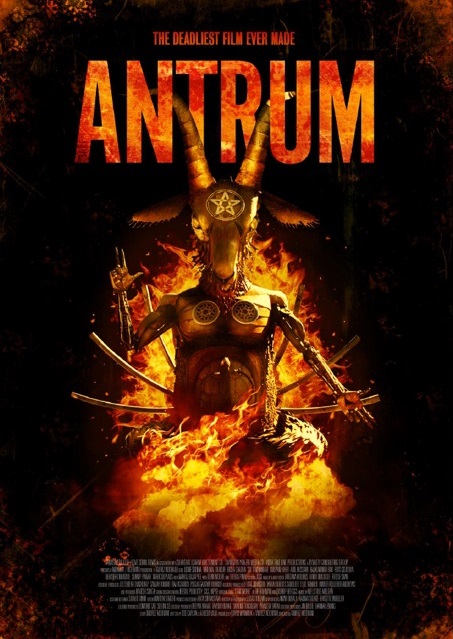

This brings us fairly neatly to Antrum: The Deadliest Film Ever Made (2018), which shares many characteristics of each of the above; there’s an oddball, somewhat intractable cursed film which only hints at any bigger message it may have, but there’s also a broader awareness of this cursed film’s reputation, and what could befall audiences who watch it. Using a brief mockumentary format to bookend Antrum itself, we are primed for the potential ill-effects of seeing the film, with examples of calamities which have befallen audiences in the past. The resulting experience is a lot stronger in premise than in execution, though, with perhaps more attention paid to the cosmetic appearance of this ‘lost film from the 70s’ than to a film which really rewards being seen. After all, if the curse ain’t real, what we are really looking for is an entertaining film – not a verdict you can easily come away with here, even whilst you might enjoy aspects of the atmosphere.

Antrum (which means ‘chamber’) follows a teenage girl, Oralee (Nicole Tompkins) and her younger brother Nathan (Rowan Smyth). Nathan is bereft after recently having his dog Maxine put to sleep; due to an offhand comment which his mother then makes about her being a bad dog, Nathan’s childish imagination therefore places Maxine in hell, something which terrifies him and gives him nightmares. In an unorthodox way of relieving his anxiety, Oralee devises a story whereby using a grimoire she’s gotten hold of, they can go and access hell itself to free Maxine. This involves digging at the spot where Satan allegedly fell to earth, which will take them down through the different levels of hell. Using on-screen titles to tell the audiences at what point they are currently, it quickly becomes apparent that their efforts to get into hell are symbolic at best, but they begin to notice odd phenomena and people around them in the remote woods: could they really have freed harmful entities? Or drawn attention to themselves in a dangerous way?

As you might well already have gathered from that summary, the plot itself is very low in the mix, with the directorial emphasis much more on sound, unusual visuals and cutaways to some unknown, unexplained scenes of torture. There are also multiple examples of occult symbols being allegedly scratched onto the film itself, leading to a deliberately multi-layered approach presumably intended to generate a sense of unease. This is referred to directly via the mockumentary frame at the end of the film, though even without this it’s pretty clear that the various sigils are intended to signify malign efforts, presumably to hex the lot of us.

Antrum is therefore fairly successful on the unease front, though I found myself craving more explication; beyond that atmosphere, the film was so thin that any genuine impact or occult content – i.e. being able to believe in the central premise or its implications in any way – was soon lost. Perhaps making this a short film, taking Antrum closer again to Ring (or at least to that film’s own cursed film) would have avoided this, and I note that directors Michael Laicini and David Amito have collectively got more experience of the short film format; Antrum is an odd choice for a full-length, all told. It’s very hard to sustain both artifice (making a film appear to be from the late 70s) and interest across a feature-length project. Whilst the ambition here is laudable, as a feature Antrum can’t quite live up to what is essentially its own hype, its notional existence as a somehow dangerous film.

Still, in terms of aesthetics, Laicini and Amito have done good work in presenting something which genuinely does look like an unearthed film reel from forty years ago. The audio track is equally very fitting to the time and place intended to have generated Antrum, nicely discordant and suitably strange for the subject matter and the style. It’s just that it doesn’t really work on a deeper level to me, which is a shame.