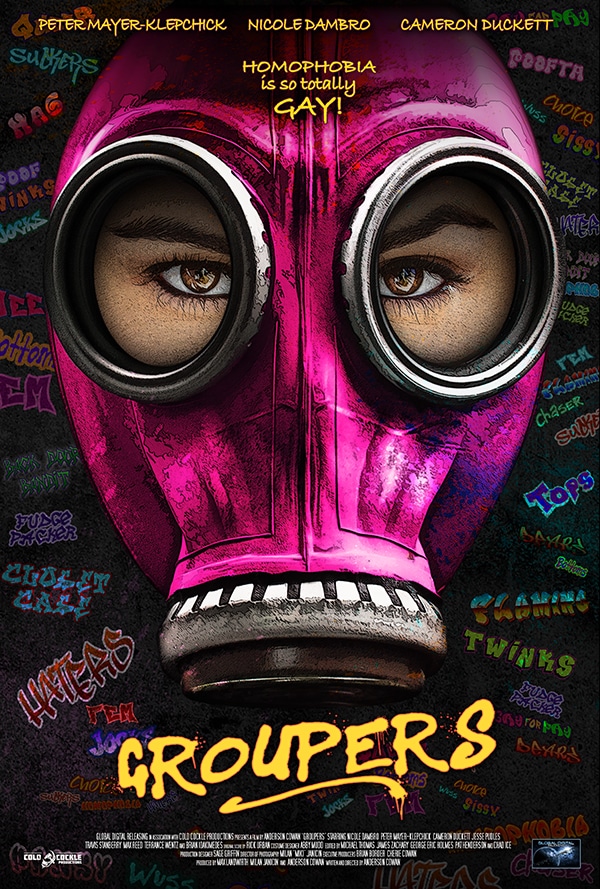

It seems that gone are the days when social commentary in cinema happened as a matter of chance; more and more, in our hyper-aware times, filmmakers actively tackle hot topics such as attitudes to sexuality, race or class – it’s there from the start, right from the beginning of the writing process. So when I saw that Groupers (2019) was being pitched as a film taking homophobia as one of its key plot points, I’ll admit that I expected something perhaps – how shall we say – intentionally ‘woke’, choc-ful of correct attitudes and lessons learned. And in that rather simplistic expectation I was completely wrong. Yes, this film challenges homophobic attitudes, but it does it in a range of ways from downright savage to fairly oblique. The film shifts from something approximating ordeal horror, to a dialogue-driven skit on human stupidity. In short, it’s immensely ambitious, and most of that ambition pays off.

The film starts with two rather hopeful jocks – the impressively moronic Dylan (Cameron Duckett) and his slightly brighter, but no nicer best friend Brad (Peter Mayer-Klepchick). They’re very pleased to be leaving a club with a pretty girl who intimates that they can both come home with her: just get into this large, empty truck, guys, and I’m yours. Naturally, they do just that. But the journey to wherever they’re going would suggest that she’s not that enamoured of them after all; slamming on the brakes, veering from side to side, oh and donning a gas mask before tossing a gas canister into the back, knocking them both out. When they revive, they’re tied to chairs (!) at the deep end of a disused swimming pool in an abandoned neighbourhood. The girl, who introduces herself as Meg (Nicole Dambro) says that they have been chosen to participate in a very special experiment. To help them make sense of their predicament, she reminds them of someone they might have forgotten…

It transpires that these jocks have been doing what jocks do best, at least if my experience of the school social system in America (which comes exclusively via cinema) has been correct: they’ve been victimising someone weaker than them, in this case for that person’s sexuality. The victim of their bullying, Oren, was Meg’s brother. And she wants to tackle Dylan and Brad’s assertions that Oren (or Aaron, they can’t quite remember his name) brought it all on himself: you choose to be gay, therefore he used his free will to think himself into a state that left him rife for victimisation.

Meg’s ideas for just how to test her own ideas are non-violent but definitely uncomfortable, and had the film began and ended with ‘people tied to chairs learning life lessons from an empowered captor’, then Groupers would for me already be filed with all the rest of the ordeal cinema already out there; also, the notion of a film where minors become the subject of sexual experimentation would be unpalatable or unsustainable to many. Just as an aside, a ‘grouper’ is apparently someone who changes their sexual orientation or gender identity later in life, and as that’s displayed loud and proud at the beginning of the film, it’s not a spoiler to add that detail here. Hold that thought, though. The film quickly breaks up any emphasis on the experiment itself with a number of features which raise this film above what it might otherwise have been.

The pace in Groupers is overall fairly quick, even for a film which comes in at nearly two hours in length. There’s comparatively little focus or fixation on the two boys and what is being done to them, as there’s a lot more plot to follow: it’s a common feature in indie filmmaking now to have your film chaptered, but it’s worth knowing that there are other characters and plot devices to come via this method, with second glances at scenes we’ve already seen; new perspectives and footage are added each time (so there’s no fixation on a single location, which helpfully breaks the film up further). The dialogue itself from all of these characters is sparky and smart, with superb performances (particularly from the driven, charismatic but fallible Meg). There’s far more in here, again obliquely for the most part, than homophobia too. Ideas about bullying in general, our relationships to social media and our attitudes to gender and race all get touched upon. In fact, as things progress, this begins to feel a lot more like a Kevin Smith-style script, an assemblage of odd people and their attitudes, all playing off one another and using just the right amount of dry humour, moving eventually from the sublime to the ridiculous. If the film loses something of its initial impetus across its running time, then it continues to be an engaging, unusual and funny film.

So, contrary to expectations, there are no grandstanding ideas about social attitudes here; attitudes are challenged, yes, but it’s as often implicit as it is explicit. The overarching appeal of Groupers must surely be its utterly unique handling of that challenging subject matter as it spirals out from the initial premise, gathers a whole host of larger-than-life characters then draws them all back together again. It deserves credit for that.

Groupers is on general release in the US from October 1st 2019.