By Matt Harries

Despite professing to not be a political film maker, William Friedkin demonstrated his social conscience at the very beginning of his directorial career. The People Vs Paul Crump was Friedkin’s 1962 debut and follows the story of the titular Crump, sentenced to death by electric chair for his part in a bungled armed robbery in which a security guard was shot dead. Friedkin, not yet 30 years old at the time, had only just begun a career in television. Having watched Citizen Kane at the age of 21 and first felt the call toward a career in film, so it was that having met Crump and being convinced of his innocence, he and cinematographer Bill Butler took up their cameras in the name of justice.

The governor of Illinois eventually saw the film and was so moved by it that he commuted Crump’s term from the death penalty to 199 years’ incarceration (Crump was eventually released on parole in 1993 before being returned to prison on less serious charges). The governor’s decision convinced Friedkin of the power of cinema. Then he went to Hollywood and was, in his own words, ‘completely dispelled of that notion.’ Within ten years of The People Vs Paul Crump he directed The French Connection and The Exorcist, two cinematic classics and as devastating a directorial one-two punch as you could wish to see. The legend of William Friedkin was established.

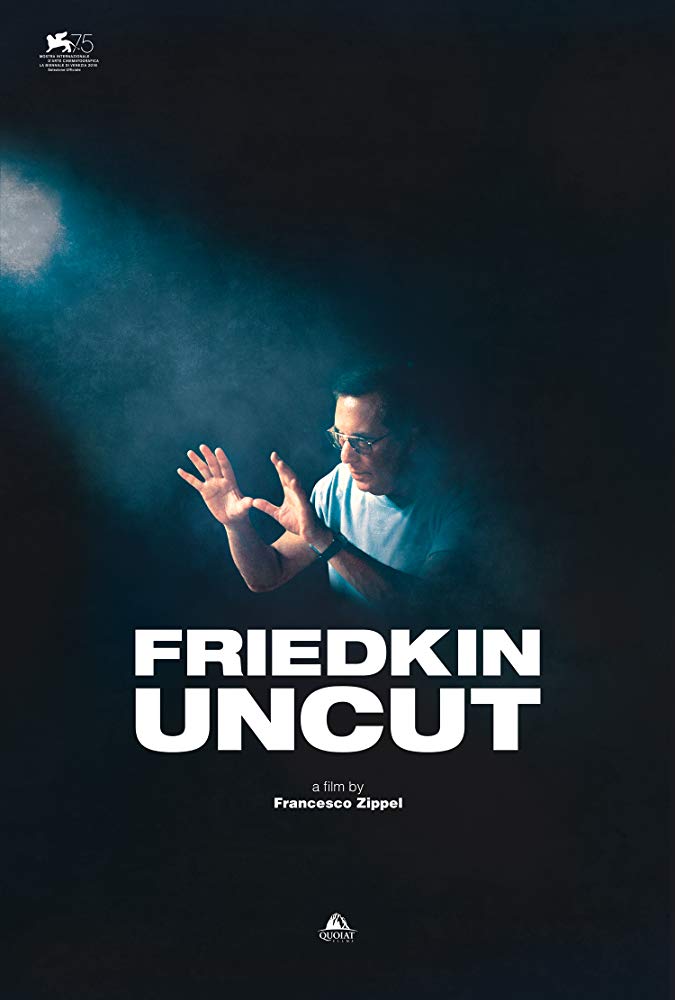

Friedkin Uncut is built around a coffee-fuelled interview at the home of the venerable director and features the input of a fairly staggering array of talent from the cinematic world, including Francis Ford Coppola, Quentin Tarantino and Dario Argento, as well as others who have worked beneath him such as Ellen Burstyn, Matthew McConaughey and Willem Dafoe. Despite this assemblage of heavyweights, Friedkin is characteristically forthright about his own work and harbours no ideas of artistic grandeur relating to his own contribution, despite taking the directorial helm on a couple of bona fide classics and a handful of less critically regarded, but still highly notable efforts such as Sorcerer, To Live And Die In L.A and his most recent full length Killer Joe. Regarding his craft as a profession and not an art, Friedkin is a director who eschews philosophising and fabrication in favour of the rawness of spontaneity and poignancy of the unvarnished truth.

This liking for an approach aligned with the Cinéma vérité tradition was apparent in 1972’s French Connection, where Friedkin shadowed police officers, even going so far as to clap the cuffs on a triple murder suspect, in a bid to absorb as much of the reality of law enforcement on the streets of Brooklyn as he possibly could. We learn of the shooting of the film’s famous car chase, a sequence Friedkin admits would not be possible to shoot on today’s health and safety conscious film sets. The director left his team in no doubt that they had not performed adequately thus far and that this take simply had to be the one.

Aside from the results of this scene – as kinetic and perilous and as ‘on the edge’ as any cinematic chase – this method of extracting the essential aliveness of the moment became a modus operandi for Friedkin, a self-confessed ‘one take guy’ who preferred to direct his actors with spontaneity rather than perfection as his watchword. Matthew McConaughey, who’s turn as Joe in 2011’s Killer Joe lead directly to his winning the role of Rustin Cohle in the brilliant first season of True Detective, speaks of the way being told to shoot in one take was a way of freeing up the actors, for whom the way forward was suddenly simple – leave everything on the table, now. Indeed whether it was dropping his trousers on set to help actress Juno Temple feel more comfortable with a nude scene in Killer Joe, or telling the studio that he would walk if Jason Miller was not given the role of Father Karras over the original choice of Stacy Keach, Friedkin is unapologetic about his methods in always striving for the utmost professionalism in the telling of a story.

Friedkin tells a great yarn and indeed has many a great yarn told about him. If a man could be judged in any way by the respect of his peers, the list of contributors to this documentary should tell its own tale. For someone who came from the era where, as Ford Coppola puts it ‘to shoot something incredible you had to do something incredible’, Friedkin is unpretentious, modest and yet at the same time unmistakably passionate about art – whether or not he sees his work as a demonstration of artistry or, perhaps instead the building of a platform that allows art to be expressed upon it. Either way, Friedkin Uncut is an essential document of one of cinema’s most enduring figures, who’s legacy is forever woven into the fabric of contemporary mythology.

Friedkin Uncut will screen as part of the Raindance Film Festival on Monday, September 23rd 2019. For more information, please click here.