This feature discusses the series in full and as such may contain spoilers.

Mike Flanagan gets it. He gets the power of horror, and he doesn’t seek to delegitimise that power by needlessly talking it up or talking it down; with his work adapting Stephen King, his films such as Oculus and (the rarely-mentioned, but superb) Absentia and now, his work directing and co-writing an innovative rendition of Shirley Jackson’s novel, The Haunting of Hill House, he’s successfully established himself as one of the most ambitious and sensitive directors currently working out there. Already, there is some discussion of a second season of The Haunting of Hill House, this year’s big TV horror hit and the subject of this feature. It’s difficult to envisage quite where this could go, or from what point, or indeed how, or if the ill-fated Crain family could be a part of this second season, but we know enough by now to know that whatever Mr Flanagan might turn his hand to would be worthwhile. Mike Flanagan gets it.

Mike Flanagan gets it. He gets the power of horror, and he doesn’t seek to delegitimise that power by needlessly talking it up or talking it down; with his work adapting Stephen King, his films such as Oculus and (the rarely-mentioned, but superb) Absentia and now, his work directing and co-writing an innovative rendition of Shirley Jackson’s novel, The Haunting of Hill House, he’s successfully established himself as one of the most ambitious and sensitive directors currently working out there. Already, there is some discussion of a second season of The Haunting of Hill House, this year’s big TV horror hit and the subject of this feature. It’s difficult to envisage quite where this could go, or from what point, or indeed how, or if the ill-fated Crain family could be a part of this second season, but we know enough by now to know that whatever Mr Flanagan might turn his hand to would be worthwhile. Mike Flanagan gets it.

I saw the original film version of the Jackson novel many years ago: re-titled simply The Haunting, this 1963 film acts as an early, very effective mesh of psychological trauma and supernatural horror, an excellent working model for the 2018 series albeit that writers Flanagan and Averill’s go far further, reinventing characters, redistributing character names and taking the implied idea of fatality forward in a series of deft, traumatic, engrossing ways. In the series, the Crain family – father Hugh, mother Olivia, and children Stephen, Shirley, Theodora, Luke and Nell – are a family of hopeful fixer-uppers, hoping to renovate the vast, stately Hill House they get at a steal, turn it over at a good profit and then plough the profits into their ‘real’ home, their ‘forever home’.

This concept of putting down roots, usually an admirable, even humdrum modern ambition, is tacitly questioned and turned around in the series, working in tandem with Jackson’s/Flanagan and Averill’s personification of Hill House and asking the question: what if the house chooses you? The Crains are often referred to as a ‘meal’ for the house; it can’t bear to leave the meal unfinished, and it wants to digest them utterly, calling them back long after (most of) them escape. To what extent they are ever able to assert themselves against this demented, relentless drive is something I’m still digesting myself, and the series conclusion is still not completely settled. However you feel about its close may well impact upon any predictions you have for a further series.

The Haunting of Hill House does so much so well, it’s difficult to know where to start, but certainly its handling of characterisation is a high point. Things are gradual. You soon identify that many of the adults in the story are also the children in the story: running these time periods parallel both makes perfect sense, and adds to the slightly disorientating feelings encouraged by the narrative at every turn. It also begs many questions, and only slowly allows us to understand the justifications for the things these children go on to do with their lives – the childhood traumas that lead them to push against death, or psychic ability, or life in general.

The Haunting of Hill House does so much so well, it’s difficult to know where to start, but certainly its handling of characterisation is a high point. Things are gradual. You soon identify that many of the adults in the story are also the children in the story: running these time periods parallel both makes perfect sense, and adds to the slightly disorientating feelings encouraged by the narrative at every turn. It also begs many questions, and only slowly allows us to understand the justifications for the things these children go on to do with their lives – the childhood traumas that lead them to push against death, or psychic ability, or life in general.

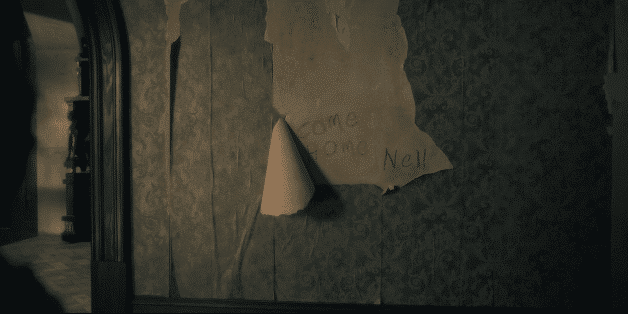

The Crains are also made relatable by their eagerness to dismiss the ostensibly supernatural things they see in their adulthoods, with Stephen in particular making an artform and a living out of denying there were ever ghosts at Hill House, his work as an author stripping back the layers of what he views as mental instability and irrationality, nothing more. And yet, he still wrestles with what he still sees. Nell is particularly vulnerable, haunted by a ghost which seems only to target her, but even the cool-headed Shirley and Theo see their share of spectres. They also try to do what adults mostly do: they block them out, they shrug them off. They can’t be real. But if, as the series asserts from the beginning that “a ghost is a wish”, then this turns the ghosts into something closer to predictions, which makes it all more vivid and terrifying.

This comes to the fore with maximum effect in Episode 5, ‘The Bent Neck Lady’. Since childhood, Nell has been afflicted with a malevolent visitation at night – a woman, face obscured, with her neck fixed at an unnatural angle. With a child’s literalness, the so-named ‘bent-neck lady’ seems to appear only to Nell, terrifying the child and driving her out of her bedroom, only to follow her downstairs to appear to her again. We follow Nell into adulthood and the events which subsume her, her short-lived happiness dissolving as her old roommate begins appearing again. This episode neatly encapsulates many of The Haunting of Hill House’s strongest features: it links ideas about time being not linear, but episodic, fate being inescapable, and the house getting its way. Poor Nell only truly understands all of this in the last frames, with that horrific ‘clunk’ as one scene rolls back in time, then back again. It truly is a staggering piece of television. Episode 8: ‘Witness Marks’ is another stand-out component of the overall series for me, with its invitation to think again about what has been seen, and is therefore ‘real’. There’s a sense of things and people unravelling here, which for me generates the strongest feeling of inescapability and a sense that the house will get everything it wants. Many of the ghosts (again, are they indeed ghosts?) are fully lit, fleshly bodies in this episode; we are encouraged to doubt them, and to think back across things we may have accepted throughout the series, before doubting everything. In less subtle terms, this episode also contains a jump scare like no other: whilst I’m not ordinarily a fan of these, it disrupts brilliantly here. I don’t think I’ve ever screamed out loud like that at anything I’ve seen on a screen, but my god, it’s a powerful shock.

This comes to the fore with maximum effect in Episode 5, ‘The Bent Neck Lady’. Since childhood, Nell has been afflicted with a malevolent visitation at night – a woman, face obscured, with her neck fixed at an unnatural angle. With a child’s literalness, the so-named ‘bent-neck lady’ seems to appear only to Nell, terrifying the child and driving her out of her bedroom, only to follow her downstairs to appear to her again. We follow Nell into adulthood and the events which subsume her, her short-lived happiness dissolving as her old roommate begins appearing again. This episode neatly encapsulates many of The Haunting of Hill House’s strongest features: it links ideas about time being not linear, but episodic, fate being inescapable, and the house getting its way. Poor Nell only truly understands all of this in the last frames, with that horrific ‘clunk’ as one scene rolls back in time, then back again. It truly is a staggering piece of television. Episode 8: ‘Witness Marks’ is another stand-out component of the overall series for me, with its invitation to think again about what has been seen, and is therefore ‘real’. There’s a sense of things and people unravelling here, which for me generates the strongest feeling of inescapability and a sense that the house will get everything it wants. Many of the ghosts (again, are they indeed ghosts?) are fully lit, fleshly bodies in this episode; we are encouraged to doubt them, and to think back across things we may have accepted throughout the series, before doubting everything. In less subtle terms, this episode also contains a jump scare like no other: whilst I’m not ordinarily a fan of these, it disrupts brilliantly here. I don’t think I’ve ever screamed out loud like that at anything I’ve seen on a screen, but my god, it’s a powerful shock.

One of my only issues with the series stems from the fact that it does something else very well, only to retreat from it (at least by a few steps). The Haunting of Hill House raises the idea of death as a state of utter nothingness – a Choronzon-worthy level of emptiness. Theodora, who protects herself from ‘reading’ people with her hands by hiding them with gloves, attempts to read her sister, Nell, by touching her body. She feels absolutely nothing – just a void, a heavy, unspeakable nothingness which infects her too, and she agonises about whether her mother and sister are out there somewhere, filled with these sensations. Nell’s brother Luke, too, ‘feels’ Nell’s death in his limbs as a cold, painful, horrifying ache. However, the resolution to this story dissipates a lot of this promise of emptiness, a promise which seems to justify the army of ghosts staring dispassionately, or even maliciously at the living. What happens to this feted feeling of void? Although the story’s handling of grief is exploratory whilst also achingly grounded in reality, some of this was lost through the end episode’s touches of sentimentality and, yeah, even some elements of whimsy. The overriding last sensation is a long stretch from happily ever after, but it certainly doesn’t feel like the expected end point, either. I wasn’t sure what to think and feel as the door closed on the ‘awoken’ Crains, but it looked an awful lot like togetherness of a kind which jarred a little against the ratcheting scares of the preceding episodes.

Still, the conclusion of any good story is a risky moment. With its blend of sudden and subtle horrors, its hidden ghosts to trick the eye, and what after all amounts to a deeply-involving story of family and loss made doubly jagged by the manifestations around them, The Haunting of Hill House has been superb. I can easily anticipate watching the whole thing again, to doubtless pick up on things I missed the first time, and to test how effectively the scares get me all over again.

The Haunting of Hill House: 5 best scenes

5 – Nell in Stephen’s apartment

Stephen is irritated; he’s just arrived at his apartment to find he’s being robbed by his younger brother and drug addict, Luke. Saddened, he gives him some stuff to go and sell, and sends him on his way. Up in the apartment, he finds Luke’s twin sister Nell, looking confused. What, were you just going to stand there and let him rob me? Stephen asks.

Nell isn’t really there. But she is trying to tell him something…

4 – Bent-neck Lady – “No, no, no, no, no, no…”

Nell is not about to sleep in her bedroom, after being woken by the ghost of a lady who seems to be fixated on her. But as she sleeps on the couch downstairs, something alerts her. As she looks up, there’s the ‘bent neck lady’ again, floating parallel above her – as we realise as the camera pans around. She’s feebly trying to speak to Nell; what she says makes horrible sense later.

Nell is not about to sleep in her bedroom, after being woken by the ghost of a lady who seems to be fixated on her. But as she sleeps on the couch downstairs, something alerts her. As she looks up, there’s the ‘bent neck lady’ again, floating parallel above her – as we realise as the camera pans around. She’s feebly trying to speak to Nell; what she says makes horrible sense later.

3 – The man with the cane

A ghost which primarily affects Luke during an episode in his childhood, this one really affected me; there’s something about the unnatural shape and size of the figure, its drifting limbs, and the silent errand it seems to be on (never take strange hats, I guess; the owners might come to retrieve them). The way this curious ghost ducks down to look at the hidden, terrified little boy when he hears him make a sound made my skin crawl.

2 – The thing in the cellar

Oh, Luke. Your subsequent drug use makes perfect sense, given some of the things which happened to you as a kid. This time, the twins are playing with the dumb waiter in the kitchen, which is electronically-operated (oh-oh). Luke, who wants to ride in the dumb waiter, finds himself in an unlit, cluttered cellar room that the family never knew existed. Something, disturbed at last, crawls eagerly towards him…

Oh, Luke. Your subsequent drug use makes perfect sense, given some of the things which happened to you as a kid. This time, the twins are playing with the dumb waiter in the kitchen, which is electronically-operated (oh-oh). Luke, who wants to ride in the dumb waiter, finds himself in an unlit, cluttered cellar room that the family never knew existed. Something, disturbed at last, crawls eagerly towards him…

1 – Road trip

This scare worked perfectly because it was so unexpected; Shirley and Theo, on their way to Hill House, are quarrelling in an escalating and angry way, but it seems as if it’s only going to be about the human drama. You relax into the fight, you forget about the circumstances. And then, in a second, a grotesque face appears between them – an absolute, horrifying, unbeatable moment of utter terror. Well played, Hill House. Well played.