If you didn’t already know from your experience of watching Basket Case that bad things are almost certainly around the corner, then you could be forgiven for thinking that the beginning of Brain Damage (1988) features a perfectly respectable elderly couple, in a well-decorated New York apartment, doing something perfectly reasonable. Sure they’re feeding…something, but that’s probably a lhasa apso or something. Dogs eat anything, so they’d surely eat, umm, brains… from an ornate china plate…erm…in the tub…pets, eh?

If you didn’t already know from your experience of watching Basket Case that bad things are almost certainly around the corner, then you could be forgiven for thinking that the beginning of Brain Damage (1988) features a perfectly respectable elderly couple, in a well-decorated New York apartment, doing something perfectly reasonable. Sure they’re feeding…something, but that’s probably a lhasa apso or something. Dogs eat anything, so they’d surely eat, umm, brains… from an ornate china plate…erm…in the tub…pets, eh?

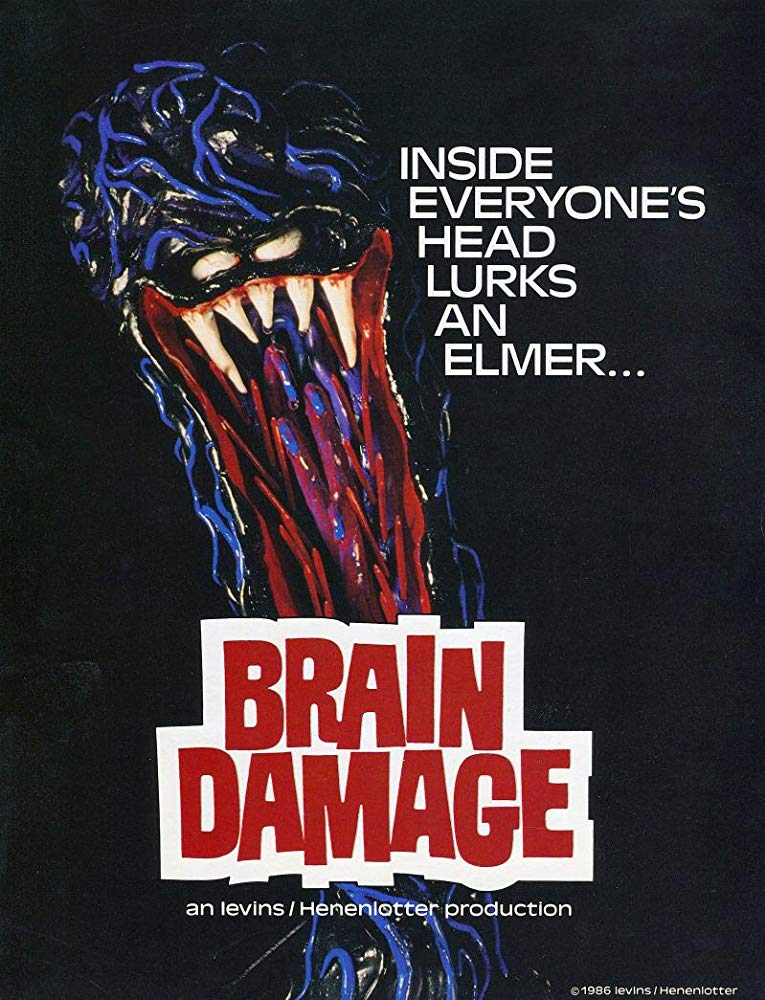

Nope, this is a Frank Henenlotter film alright, so once you see the ‘beautiful’ animal brains and the couple’s distraught reaction when it transpires that ‘Elmer’ (“you fucking named it Elmer?”) has disappeared from their bathroom, you know things are about to get nicely weird. The old couple immediately tear their apartment apart looking for whatever-Elmer-is, intruding on the neighbours and growing increasingly hysterical. Cut to a different apartment in the block, one as yet undisturbed by this pair of howling septuagenarians; here we meet a young man called Brian (credited as Rick Herbst, though actually Rick Hearst). Brian likes to sleep. Or, is it more than that? He thinks he might be falling sick, and certainly can’t go out that night as planned with his girlfriend, Barbara. Soon, he discovers he’s been bleeding from the back of the neck, then he begins hallucinating. Clearly, something is very wrong with him…

“A life of light and pleasure!”

…and it’s not just a nasty bug. It’s more of a charming, well-spoken eel-like thing with human eyes and a mouth which can inject a hallucinogenic fluid into its witting, or unwitting hosts. This is ‘Elmer’, or the Aylmer, depending on who you ask – I’m going to refer to him as Elmer though, given the film lists ‘Elmer’s Song’ on the credits and disbelief about his name also gives us one of the film’s funniest lines (see above). Anyway, Elmer explains to Brian that he’s going to have a new, exciting life thanks to him. All Brian has to do is take him out for a little ‘walk’ from time to time, and if he does, he’ll get to experience a high like no other. True enough, when Elmer injects some of his ‘juice’ into Brian’s brain via that hole in his neck, Brian does have a different kind of trip, one where a scrapyard turns into a nightclub (and, later, a nightclub turns into a diner – at least for Elmer). But the pink cloud doesn’t last long, never does: those close to Brian are concerned by his immediate personality overhaul, his new penchant for a million locks on his door and his tendency to keep pails of water in his bedroom. Meanwhile, the demands being made by Elmer are growing more and more serious.

So how can Brian get out of a situation where he’s regularly being made an accessory to murder? He’s not a bad guy, not really, and sadly the advice of his knowledgeable neighbours comes a little too late. Elmer is too strong by this point, and although he’s about 20 inches high, he’s still the one calling the shots. Brian’s desperate attempts to get clean away from his roommate at the seedy Sunshine Hotel are tragicomic, and very grisly, with deeply traumatic hallucinations. Sure, there’s a weird creature mocking him with song from the handbasin, but it’s hard not to feel sorry for Brian at this stage; creature feature or not, here’s a guy struggling on one hand to remember what he’s done when under the influence, and on the other hand, to get back his personal control. Anyone who’s been in a similar situation, or knows someone who has – hopefully minus the warbling neck parasite, but let’s not make assumptions – could sympathise with that. This fight for control is tough going, and ultimately it costs Brian and the people who try to help him more than they can afford to give.

It hardly needs saying that Brain Damage could work as a hideous metaphor for addiction. The highs, the lows, the people hurt, the desperate measures – they’re all in there. In fact the film seems to invite us to see Brian in this light on several occasions: as he prepares to head into the new wave gig where he meets the unfortunate fellatio brain-munch girl, for instance, there’s a back-and-forth shot of him getting his hit with an alcoholic down-and-out standing just a little way away, drinking from a brown paper bottle. Their ages are different and the substances are different, but these are both people with their dependencies.

It hardly needs saying that Brain Damage could work as a hideous metaphor for addiction. The highs, the lows, the people hurt, the desperate measures – they’re all in there. In fact the film seems to invite us to see Brian in this light on several occasions: as he prepares to head into the new wave gig where he meets the unfortunate fellatio brain-munch girl, for instance, there’s a back-and-forth shot of him getting his hit with an alcoholic down-and-out standing just a little way away, drinking from a brown paper bottle. Their ages are different and the substances are different, but these are both people with their dependencies.

Still, as much as that’s all present and correct, the film is far more than just as elaborate, icky allegory. It’s also a highly original, unsettling and squirm-inducing monster movie. Sure, Elmer isn’t smashing down buildings or drinking the blood of virgins, but he’s sly, powerful, wreaking havoc and destroying people’s bodies in ways which wouldn’t be lost on many a screen monster. Under his influence, Brian’s high, his comedown and his head-shattering OD are anything but conventional. The film takes all of this just the right amount of seriously, with Brian’s curiosity gradually turning into cold acceptance that his old life is over, matched against Elmer’s jovial disdain for everyone, all voiced by (uncredited) old school horror host John ‘Zacherley’ Zacherle, which lends him an odd gravitas. The given history of the Aylmer is also nothing short of inspired, and makes this smooth-talking critter, who apparently dates back to the 4th Crusade, seem all the more oddly worldly.

Still, at least Elmer is frank about being an asshole. The New York Brian is encouraged, then made to stalk on Elmer’s behalf is not full of particularly nice people. Brian’s identikit roommate/brother Mike has clear designs on Barbara, though fraternal loyalty keeps him off her for the short term at least. This leads to another side-by-side shot where Mike and Barbara are in bed, whilst in the next room (unbeknownst to them) Brian is getting off in, ahem, his own way. Then there’s the disgruntled neighbour (a reprise for actress Beverly Bonner) who is primed to be angry before she even sees what her elderly neighbours want; the scrapyard nightwatchman who is so full of his own importance that he’s happy to pull a gun on a lone kid; the Sunshine Hotel which has people intent on having a good time before nuclear armageddon inevitably cuts their fun short. There’s a lot of folk in this film who aren’t exactly amenable to playing nice, and a lot of people happy to look the other way, a fact that Elmer exploits. Even the guy on the metro with the mysterious basket decides he’d be better off moving along (yep, that’s Kevin Van Hentenryck and his brother Belial again), which contributes to Barbara’s eventual unhappy fate.

“I’m you, Brian. I’m all you’ll ever need.”

As much as I love all of Henenlotter’s films, Brain Damage is really my favourite. On a low budget, and with inexperienced actors (this was Rick Hearst’s first film) it achieves a great deal, striking a good balance between authentic horror and horror-comedy. It has a lot of the gritty, grimy nastiness of Basket Case, with the same mean streets and locations, content so graphic that it was excised from early cuts of the film, and horrible subject matter: in some respects it’s like Basket Case in reverse, with an unwitting joining-together of two sentient creatures, one ‘normal’ and one not, instead of an enforced coming-apart. So this whole symbiosis theme is pretty grim, and gives us some unpleasant scenes throughout.

As much as I love all of Henenlotter’s films, Brain Damage is really my favourite. On a low budget, and with inexperienced actors (this was Rick Hearst’s first film) it achieves a great deal, striking a good balance between authentic horror and horror-comedy. It has a lot of the gritty, grimy nastiness of Basket Case, with the same mean streets and locations, content so graphic that it was excised from early cuts of the film, and horrible subject matter: in some respects it’s like Basket Case in reverse, with an unwitting joining-together of two sentient creatures, one ‘normal’ and one not, instead of an enforced coming-apart. So this whole symbiosis theme is pretty grim, and gives us some unpleasant scenes throughout.

But for all that, the witty script knows when to stop, when to give us a breather. Brain Damage has more than its share of funny, playful moments throughout, from Brian’s manic dinner date to Elmer’s big band style ditty and certainly to his own appearance; his part-creepy, part funny looks we can credit to SFX guys Gabe Bartalos and David Kindlon, who to give them due credit designed a creature we’ve not really seen the likes of since. Finally, this is a very creative film in several aspects, from that script to the effects and beyond. I’ve already alluded to the potted history of the Aylmer given during Brain Damage, and I noticed that there’s a credit for a historical researcher on the film, which I can only imagine was for this description of his chequered history; it certainly goes above and beyond what you might expect in a horror/exploitation style film, as do some of the effects: the hallucination of the ceiling light/unblinking eye, as a key example, is an inspired sequence in its own right.

Henenlotter wasn’t done with arguably his most famous film – Basket Case – at this juncture, going on to make two sequels in the ensuing years, as well as making Frankenhooker – one of the funniest horror comedies of the 80s (more anon). Some Basket Case fans weren’t entirely taken with Brain Damage, but I kind of hope that in the decades since, they’ve been able to revise their opinions and now see the film’s many strengths, even if ultimately they prefer asking ‘what’s in the basket?’ To me, Brain Damage is a funny, gruesome piece of work which plays around with what could have been a weird little mythos all of its own, as well as studying addiction through the lens of a creature feature whilst never losing sight of the film’s coltish, crazy aspects. It’s a film which always screams ‘weird 80s’ to me, and I think a lot of people who were weird in the 80s will, equally, always have a soft spot for Brain Damage. If nothing else, have we ever seen a mind get quite so literally blown as we see it here?