Times of great uncertainty and bloodshed have always seemed to bolster paranoia and irrational thought. Change offers to dispose of the unconscionable practices of the past, but even as old beliefs and practices are on the verge of being swept away, people still to seek them out, retreating into watchful suggestibility any time the pace of change progresses too quickly. You might like to name any number of examples from history, but in terms of the English Civil War – which provides our context here – a countrywide dispute over governance, supported by new warfare and weaponry, continued to cast a long shadow, and people did not simply forget what had gone before; far from it. Suspicions over one’s neighbours were still framed by supernatural suspicions, or at least framed in compelling supernatural language; in a similar way to today, where people gloss over the complex, uncomfortable truths to look instead for clues about conspiracies, the people of the mid-17th Century accused one another of witchcraft. Discerning opportunists, like the ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins, were all too willing to exploit this.

Times of great uncertainty and bloodshed have always seemed to bolster paranoia and irrational thought. Change offers to dispose of the unconscionable practices of the past, but even as old beliefs and practices are on the verge of being swept away, people still to seek them out, retreating into watchful suggestibility any time the pace of change progresses too quickly. You might like to name any number of examples from history, but in terms of the English Civil War – which provides our context here – a countrywide dispute over governance, supported by new warfare and weaponry, continued to cast a long shadow, and people did not simply forget what had gone before; far from it. Suspicions over one’s neighbours were still framed by supernatural suspicions, or at least framed in compelling supernatural language; in a similar way to today, where people gloss over the complex, uncomfortable truths to look instead for clues about conspiracies, the people of the mid-17th Century accused one another of witchcraft. Discerning opportunists, like the ‘Witchfinder General’, Matthew Hopkins, were all too willing to exploit this.

Hopkins, a notorious figure in his own lifetime, successfully combined the contemporary spirit of enterprise with the old beliefs in pacts with the devil, turning a lucrative trade with a regimented programme which extracted confessions of witchcraft. Little is known of his origins, save where he was born and to whom, but as the son of a Puritan minister he may well have been a believer in the power of Satan to mislead and menace (albeit it’s always seemed odd that Old Scratch did so in such typically low-key ways). But, if Hopkins was pious enough to believe in witchcraft, then he was not such a Christian when it came to poverty and charity, and detecting witches – often with sadistic methods – was a real money-spinner for him. Hopkins was not idle, and he was not cheap. He executed more witches during his brief career than England had dispatched in the previous 160 years, and demanded so much money for doing so that he cost a single town over £3000 in modern money in ‘costs’. Whilst his rapidly-generated wealth couldn’t insulate him from illness and premature death (it’s believed he was dead of tuberculosis by 30), it’s clear to see why his short, hectic career has proved a source of inspiration for literature – and film. In 1968, based on a novel by Ronald Bassett, director Michael Reeves and the head of Tigon Films, Tony Tenser, worked together on a screenplay and script. After a protracted battle with the BBFC over the film’s ‘sadism’, shooting began in England in the autumn. This was itself the start of a turbulent and uneasy process, but the end result has given us one of the seminal horror films of the twentieth century.

“You took him from me!”

The plot sticks with the turmoil of civil war for its context, and presents us the implications of witch-hunting in microcosm, focusing largely on how the arrival of the now-named Witchfinder General impacts upon one family. Hopkins (Vincent Price) and his assistant Stearne (Robert Russell) are moving from place to place in the English countryside, fuelling intolerance and aggression as they go; meanwhile, a roundhead soldier named Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy) is all too aware of the potential risk of Hopkins’ presence, and struggles to balance his duties as a soldier against his desire to keep his fiancée Sarah (Hilary Dwyer) safe from harm. He is utterly unable to do this, ultimately, and finds himself mired in a bitter power struggle against Stearne and Hopkins, vowing vengeance against Hopkins for the torments he goes on to inflict against Sarah and her father.

This, as a plot synopsis, looks oddly thin on the page – but the film’s all-encompassing atmosphere, together with its sense of dread purpose and inescapability, fleshes out its storyline to an unbearable point. Those drab, indifferent landscapes and the marching lines of men all seem to crowd inwards as the plot progresses, whilst the systematic dismantling of the happy future Marshall once anticipated has the power to engender great anger. Ogilvy’s rage that he cannot fully sate his desire for bloody revenge upon Hopkins calls oddly to our sympathy as an audience; he is frozen forever in his moment of supreme frustration, and whilst we do not see what happens to him next, the way in which he is overwhelmed by bigger social and political forces confronts us with the distasteful impression that all rebellion is ineffectual. The young man’s life is effectively over at that moment; we leave the story to the soundtrack of one of the great cinematic screams.

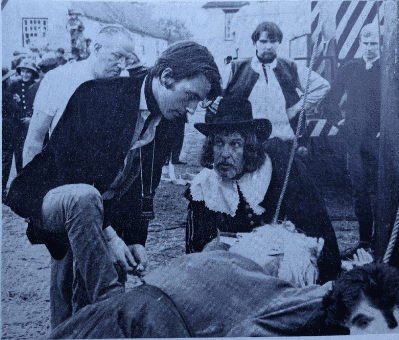

The troubled making of the film is as notorious as the events of the film itself, and much has been made of Michael Reeves’ fury at the studio pressure which forced him to cast Vincent Price in his lead role. It’s well-documented that he was rude and dismissive of Price, whilst Price remembered the experience of making Witchfinder General as the only time he ever really clashed with a director. I can see why Reeves was wary of casting Price, as he was hardly known for the type of film which the younger man was setting out to make, though some of the heated exchanges between them are hardly defensible – but Price’s acknowledged disillusionment with the film lends him a miserable gravitas in-role which is note-perfect. Many of the film’s sinister attributes come directly from Vincent Price’s performance, although the supporting cast are superb. I also feel that the casting of a much older man than the real Hopkins would have been works to the film’s advantage. Price is able to bring a rather jaded, menacing presence to the film, and he acts as a perfect foil for Ogilvy, the young career soldier. The two men are the embodiment of the old and the new, and on screen, the effect is mesmerising. Price himself, once safely back in the California sunshine, was able to acknowledge that Witchfinder General’s troubled birth had in fact led to one of his best-ever performances, and, ever the gentleman, he wrote to Reeves to say so.

The troubled making of the film is as notorious as the events of the film itself, and much has been made of Michael Reeves’ fury at the studio pressure which forced him to cast Vincent Price in his lead role. It’s well-documented that he was rude and dismissive of Price, whilst Price remembered the experience of making Witchfinder General as the only time he ever really clashed with a director. I can see why Reeves was wary of casting Price, as he was hardly known for the type of film which the younger man was setting out to make, though some of the heated exchanges between them are hardly defensible – but Price’s acknowledged disillusionment with the film lends him a miserable gravitas in-role which is note-perfect. Many of the film’s sinister attributes come directly from Vincent Price’s performance, although the supporting cast are superb. I also feel that the casting of a much older man than the real Hopkins would have been works to the film’s advantage. Price is able to bring a rather jaded, menacing presence to the film, and he acts as a perfect foil for Ogilvy, the young career soldier. The two men are the embodiment of the old and the new, and on screen, the effect is mesmerising. Price himself, once safely back in the California sunshine, was able to acknowledge that Witchfinder General’s troubled birth had in fact led to one of his best-ever performances, and, ever the gentleman, he wrote to Reeves to say so.

“Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips” – the influence and legacy of the film

Perhaps predictably, the film was decried for its gruesome “sadism” upon release, even though many of the bloodier elements had been rinsed from the screenplay at the BBFC’s behest before filming even took place. It’s always strange to consider those people who are outraged by the inclusion of grisly scenes which perfectly match the subject matter (and have usually been cleaned up considerably; I’d imagine the real battle of Naseby was worse than anything Reeves could have got on screen). As with the recent, predictable flounce-outs from the new Lars von Trier film in Cannes, you wonder what on earth people expect, or why they go to see anything which they must guess won’t be at all to their tastes.

Longer term, however, audiences began to re-assess, identifying the strengths and the bold decisions, eventually seeing Witchfinder General for the striking, innovative addition to the horror canon which it is. This has taken time, but its reputation is now cemented, and it’s often included on lists of the best horror films of all time. Funnily though, one of its earliest successes was to reinvigorate Edgar Allan Poe as a source of cinematic inspiration, despite Reeves’ original screenplay having nothing to do with Poe whatsoever. AIP, who had part-budgeted the film (and insisted on their most bankable star getting the lead role) re-released it in the US under a different title, ‘The Conqueror Worm’, which is a line from a Poe verse which the author embedded into one of his short stories, Ligeia. To justify the rebrand, the new version of the film was bookended by verses from the poem, though there were no other additions. This new title hardly set the world ablaze on its release, but overall, Reeves’ film led to a minor resurgence in Poe adaptations, including The Oblong Box: it’s not as gaudy or glorious as The Masque of the Red Death, but it’s certainly worthwhile.

In terms of an English cinematic legacy, Witchfinder General has come to be widely-credited for its influence on what’s now broadly referred to as ‘folk horror’: this is a very broad church overall, but one which often derives its terrors from landscape, seclusion and the pesky resurgence of old gods. Whilst Witchfinder General’s relationship with the supernatural is rather minimal, positioning its witchcraft as a bludgeoning tool of exploitation and repression used by the powerful, its trials and burnings take place in a rural 17th century setting which seems primed for sinister events, offering contrast and incongruity whilst exploring a period in time when fervent Christian belief was meant to be at its apex. If the society of Witchfinder General needlessly burned its witches, then Blood on Satan’s Claw, with its slightly later setting, goes a step further by ploughing up a real devil for people to worship. The thread of sinister communities and historical unreason started in 1968, travelled to Europe in films such as Mark of the Devil, and in the years since, a resurgent interest in these folk horrors has led to modern-day films like A Field in England (2013), also set during the English Civil War. Its characters could almost be contemporary with the characters in Michael Reeves’ film.

In terms of an English cinematic legacy, Witchfinder General has come to be widely-credited for its influence on what’s now broadly referred to as ‘folk horror’: this is a very broad church overall, but one which often derives its terrors from landscape, seclusion and the pesky resurgence of old gods. Whilst Witchfinder General’s relationship with the supernatural is rather minimal, positioning its witchcraft as a bludgeoning tool of exploitation and repression used by the powerful, its trials and burnings take place in a rural 17th century setting which seems primed for sinister events, offering contrast and incongruity whilst exploring a period in time when fervent Christian belief was meant to be at its apex. If the society of Witchfinder General needlessly burned its witches, then Blood on Satan’s Claw, with its slightly later setting, goes a step further by ploughing up a real devil for people to worship. The thread of sinister communities and historical unreason started in 1968, travelled to Europe in films such as Mark of the Devil, and in the years since, a resurgent interest in these folk horrors has led to modern-day films like A Field in England (2013), also set during the English Civil War. Its characters could almost be contemporary with the characters in Michael Reeves’ film.

Hopkins has even made his way into pop culture, from Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens to TV comedy (via an affectionate pastiche called Scream Satan Scream! in Doctor Terrible’s House of Horrible) and even music: the genre of doom metal has an especial soft spot for the ol’ Witchfinder, naming bands, EPs and songs for him. Many metal fans first heard Vincent Price speak as Hopkins in a certain Cathedral song, years before they actually saw the film…

It’s a shame, or at least I personally think it is, that we never got to see Udo Kier playing Hopkins in his redacted scenes from Rob Zombie’s Lords of Salem – but, now that director Nicolas Winding Refn has purchased the rights to Witchfinder General, we may in future see a new incarnation of Hopkins which is a long way from what Reeves ever envisioned (and no doubt a long way from anything Zombie/Kier had in mind, either). We can be cautiously optimistic about any future developments from Refn, I think, as he’s a talented, distinctive filmmaker who would respect the film’s legacy. But until then, fifty years after its inception, Witchfinder General remains a singularly English chapter in horror. It’s brutal, it’s influential, and in overarching meanness of spirit, it’s a horror film which is still quite unparalleled today.