Meiko Kaji is, from a Western perspective, one of the most unmistakable and recognisable Japanese actresses of all time, but this comes with a significant proviso. Most of us know just a tiny fraction of the films she has ever made; only a handful of these nearly one hundred films have really made it over here anyway, and even out of that, we tend to think of her in one of a couple of key roles. Either Meiko Kaji is ‘Scorpion’, the largely mute and indestructible prison inmate of the Female Prisoner series, or she is the sword-wielding agent of doom in Lady Snowblood. This is a state of affairs acknowledged by author Tom Mes in his neat Meiko Kaji book Unchained Melody, available now on the Arrow Books imprint (and thus an extension of the work which Arrow has so far done in publicising Kaji’s work via their existing range of Meiko Kaji releases.)

Meiko Kaji is, from a Western perspective, one of the most unmistakable and recognisable Japanese actresses of all time, but this comes with a significant proviso. Most of us know just a tiny fraction of the films she has ever made; only a handful of these nearly one hundred films have really made it over here anyway, and even out of that, we tend to think of her in one of a couple of key roles. Either Meiko Kaji is ‘Scorpion’, the largely mute and indestructible prison inmate of the Female Prisoner series, or she is the sword-wielding agent of doom in Lady Snowblood. This is a state of affairs acknowledged by author Tom Mes in his neat Meiko Kaji book Unchained Melody, available now on the Arrow Books imprint (and thus an extension of the work which Arrow has so far done in publicising Kaji’s work via their existing range of Meiko Kaji releases.)

Mes provides here a meticulous and exhaustive filmography, starting at the very beginning of Kaji’s career with her shortcomings as an ojo-sama, or a ‘well-bred young lady’, the kind of girl generally sought-after in the Japanese cinema of the early 1960s, and how this soon led to rather meatier and more challenging roles – even though this doesn’t mean she was ordinarily as taciturn as she seemed in the Female Prisoner films, and the book does well to point this out. As a means of adding structure to the book, Mes has closed each chapter with a mini-biography of a number of significant directors with whom Kaji has worked – the likes of Masahiro Makino, Yasuharu Hasebe and of course Shunya Ito all figure. He also talks us through her work for a range of successful Japanese studios, each with their own key styles and themes, each who had to adapt, or sink as audience tastes altered. There are also other chapters, one on Kaji’s TV work – a complete void to me, and probably to many other readers – and a chapter on her musical career, although this of course goes hand in hand with her film and TV work. It’s nonetheless interesting in its own right.

There is a tremendous amount of knowledge on display in this book: it’s almost overwhelming in places, perhaps because a lot of these projects are so broadly unknown to us, but for anyone with a desire to know more about Kaji’s career then this book would be an excellent roadmap to guide them through. The emphasis here is very much on the acting work itself, however: this is not a biography in anything but the loosest sense, with little comment on what may have been going on in Kaji’s personal life during her career, for instance. The author’s initial recounting of an interview with the actress in Tokyo in 2006 was clearly a defining moment for him (and I’m not bloody surprised) but it feels unclear whether any specific parts of this interview thread their way through the rest of Unchained Melody; I suspect a lot of existing commentary, from a variety of sources, has been brought together here too. It’s not that the book doesn’t feel personal, exactly, just that the author’s fandom is revealed via his comprehensive knowledge and a range of interesting asides about Japanese culture pertaining to various films and audience trends along the way. This can mean footnotes which would just as comfortably fit into the main body of text, but it all goes to show that Tom Mes knows his stuff and wants to share as much as possible.

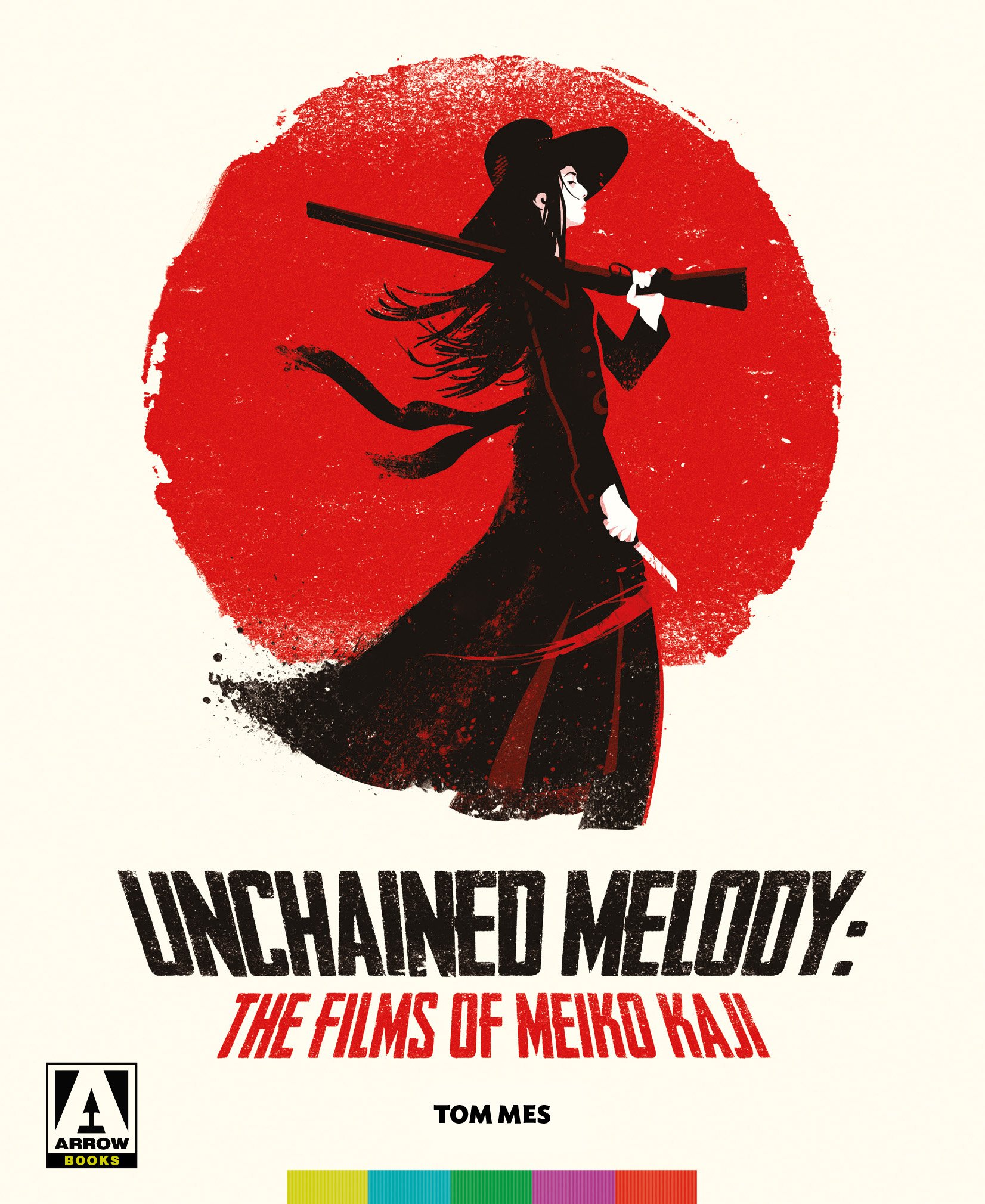

This is, despite its detailed approach, a slim volume: it comes in at just over 150 pages, including references, acknowledgements and so forth, in a compact and bijoux 17 x 14cm format. It’s an appropriately attractive book too, with a number of full-page colour images, a large range of hitherto-unseen stills and behind-the-scenes pictures, even including Meiko Kaji grinning (!) out of a Sunsilk shampoo print advert from the 1970s. Unchained Melody also boasts excellent custom colour cover illustrations by artist Nat Marsh.

Unfortunately the book can’t (and doesn’t attempt to) answer the big question, which is: why aren’t current directors, Japanese or otherwise, falling over themselves to hire Meiko Kaji now, considering her documented avowed desire to act again? This is even after her name reappeared in the limelight in the wake of Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill series, and even allowing for a couple of unhappy incidents which took her out of the running for a few projects in the noughties. Ah well, we can only hope that renewed interest in her career, coming across through ventures like this book, might lead to audiences seeing her again in cinema. In the meantime, this is a solid piece of work and a definitive guide to Meiko Kaji’s career – hopefully her career to date.

You can find out more about buying Unchained Melody: the Films of Meiko Kaji here.