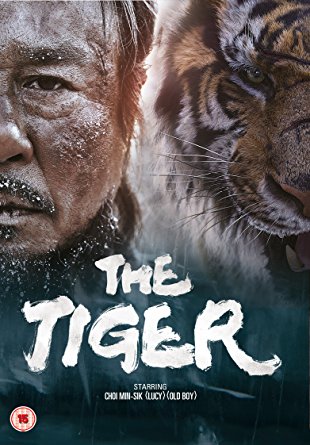

Sometimes a film self-consciously goes for the ‘epic’ tag, and it’s clear from the very outset that this is the case with Park Hoon-jung’s 2015 movie The Tiger. With its sweeping Korean vistas, Sturm und Drang musical score and lone figure set against an unforgiving world it clearly fits the bill, and actually that’s just fine: it’s a genre which seems to suit actor Choi Min-sik, perhaps best known for his work in the groundbreaking Oldboy (2005) which was in many ways an ordeal horror epic, when you think of it now, a decade or so on. However, in its painstaking attempts at detail in this rather artistic study of cruelty, the film is certainly an epic-length two hours, forty minutes in duration. This is more and more the trend in cinema these days, but I strongly feel that The Tiger could have curtailed one or two hunt scenes, for example, and retained or even improved much of its impact.

Sometimes a film self-consciously goes for the ‘epic’ tag, and it’s clear from the very outset that this is the case with Park Hoon-jung’s 2015 movie The Tiger. With its sweeping Korean vistas, Sturm und Drang musical score and lone figure set against an unforgiving world it clearly fits the bill, and actually that’s just fine: it’s a genre which seems to suit actor Choi Min-sik, perhaps best known for his work in the groundbreaking Oldboy (2005) which was in many ways an ordeal horror epic, when you think of it now, a decade or so on. However, in its painstaking attempts at detail in this rather artistic study of cruelty, the film is certainly an epic-length two hours, forty minutes in duration. This is more and more the trend in cinema these days, but I strongly feel that The Tiger could have curtailed one or two hunt scenes, for example, and retained or even improved much of its impact.

The film is set over a period of around ten years, starting in 1915. Korea, long before it was split into a ‘North’ and a ‘South’, was at the time occupied by the Japanese – a nation which partook of a fair bit of empire-building during the twentieth century. We first meet our protagonist, Chun Man-duk (Choi) during this year: all happiness is relative, so although his life as a mountain hunter seems remarkably tough and fraught, he clearly enjoys a happy marriage and he is teaching his infant son the hunter’s craft. A chance encounter with a tiger – one of Korea’s last remaining tigers – is a dramatic moment at which we leave Man-duk, however, and the action moves forward by a decade.

The Japanese are still trying to drum out the last Korean insurgents in Man-duk’s Mount Jirisan jurisdiction, and for some unexplained reason, one of the military commanders, General Maijono, has made it his personal business to kill off the last tigers too. There’s a mawkish kind of sadness to all this: in a luxuriant room plastered with taxidermy, it seems the old general simply has a fetish for dead creatures, or just sees them as lucrative, which to be fair many of the local hunters – Man-duk included – also do. However, perhaps there’s some symbolism here, too: being the ones to kill the last, largest tiger would be the ultimate one-upmanship over the local population, even if ultimately the Japanese still need their help in order to do it.

And what of Man-duk? Well, he’s still living, but no longer works as a hunter. His son, now a teenager, is growing frustrated with their solitary, penniless existence, and wants to hunt, just as his father once did. Man-duk’s wife, however, is no longer to be seen. Gradually, we piece together the story of the intervening ten years, and find out why Man-duk now prefers to sell medicinal herbs, rather than living by his old skills. The linking factor here is an old, fearsome male tiger: the Japanese want this ‘Mountain Lord’, as do the locals; they try to entice Man-duk to help them, but it seems he has a terror of this particular beast.

This whole ‘man vs beast’ aspect of the film feels rather like The Revenant in places, a film which is its 2015 contemporary. Unlike the outraged mama bear in The Revenant, though, the ‘Mountain Lord’ here is more than an animal in many respects; the film plays fast and loose with animal realism in its (well-utilised) CGI sequences, and although the film is unsettlingly gruesome in its hunt scenes, there is a certain level of disparity of threat here too, as on occasion, the tiger becomes semi-mythic, something akin to a moral arbiter of the characters, killing savagely sometimes, but interacting rather differently sometimes. This shifting identity is something of a sticking point in the first half of the film; it’s not clear, for much of this time, what the tiger actually is. Still, eventually, a parity is created between the hunter and the tiger, which makes ever greater sense as the narrative progresses.

This whole ‘man vs beast’ aspect of the film feels rather like The Revenant in places, a film which is its 2015 contemporary. Unlike the outraged mama bear in The Revenant, though, the ‘Mountain Lord’ here is more than an animal in many respects; the film plays fast and loose with animal realism in its (well-utilised) CGI sequences, and although the film is unsettlingly gruesome in its hunt scenes, there is a certain level of disparity of threat here too, as on occasion, the tiger becomes semi-mythic, something akin to a moral arbiter of the characters, killing savagely sometimes, but interacting rather differently sometimes. This shifting identity is something of a sticking point in the first half of the film; it’s not clear, for much of this time, what the tiger actually is. Still, eventually, a parity is created between the hunter and the tiger, which makes ever greater sense as the narrative progresses.

The performances here are strong, although the Japanese (albeit occupying comparably little screen time) are far more in the line of straightforward villains – moustachioed and all. Choi Min-Sik is superb, and the relationship between him and his young son is plausible, even if there are a couple of moments of maudlin sentimentality; there are also a few strange moments of levity during the film, which aren’t perhaps the best fit for me, but they do punctuate the otherwise unrelentingly grim pursuit of the Mountain Lord. The use of flashbacks, to fill in the back story of the intervening ten years, is well-used and definitely helps to maintain interest to the film’s story.

It’s just so, so long. I’m all for a sombre pace wherever it works, and a flashy, high-action film wouldn’t have suited the subject matter at all, but it does feel like some of the scenes here could have happily hit the cutting-room floor (so to speak). As I mentioned in the introduction to this review, there are – for example – a number of gory hunt scenes where the tiger’s abilities border on supernatural, and we are shown at length the animal cutting a swathe through the hunters; as pleasing as this is, however, I feel that the same effect could have been accomplished with less of it. The film risks being laborious or repetitive in places, and nothing can unhinge an epic like tedium.

Still, my overall opinion of The Tiger is positive: ultimately, it’s a brutal parable of a difficult, changing world and how the microcosm of human, and animal grief plays out against this backdrop. This film is a moving work of art, a Jeong Seon painting turned into a narrative, and on these grounds alone it’s certainly worthwhile.

The Tiger is available now from Eureka Entertainment.