I will confess that I have had no prior experience of director Yorgos Lanthimos’s work, but based on his most recent film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, I’d imagine that a little goes a long way. That isn’t to say that I wasn’t completely drawn in to this twisted story of unhappy families, but that it’s left an unseemly, faintly uncomfortable after-effect; I found myself squirming in (rewarded) anticipation of horrible violence, and soon after, laughing at things I definitely didn’t feel I should be. It has all conspired to create a queasy sensation, one which clearly took work to establish, and isn’t going away in a hurry.

I will confess that I have had no prior experience of director Yorgos Lanthimos’s work, but based on his most recent film, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, I’d imagine that a little goes a long way. That isn’t to say that I wasn’t completely drawn in to this twisted story of unhappy families, but that it’s left an unseemly, faintly uncomfortable after-effect; I found myself squirming in (rewarded) anticipation of horrible violence, and soon after, laughing at things I definitely didn’t feel I should be. It has all conspired to create a queasy sensation, one which clearly took work to establish, and isn’t going away in a hurry.

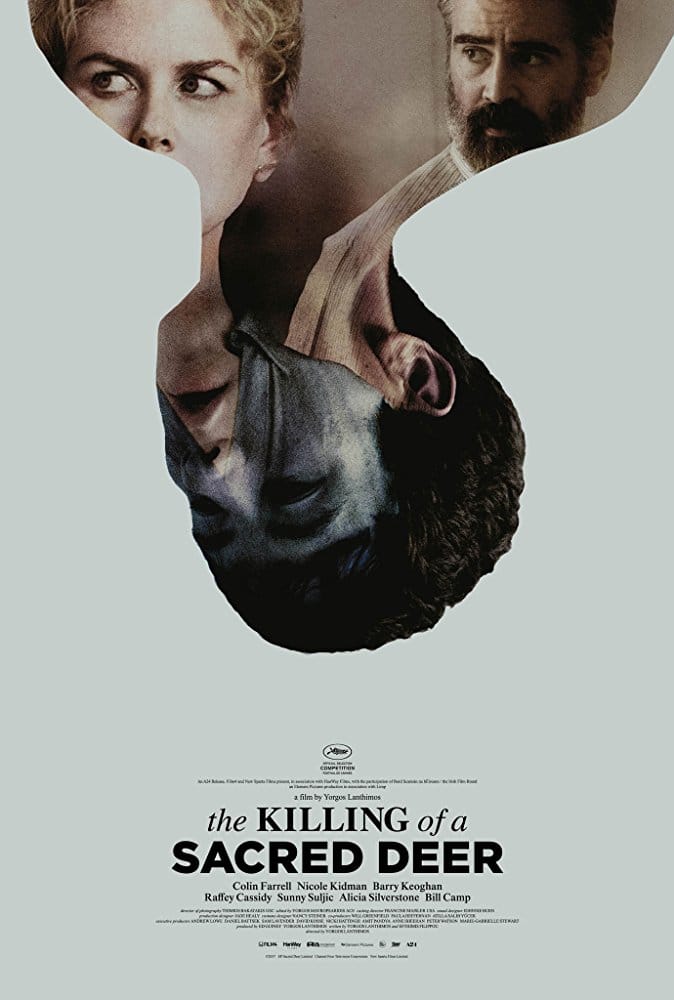

Starting as it goes on throughout – by reducing people down to a series of often vulnerable and even somehow pathetic bodily processes – we see cardiac surgeon Steven Murphy (Colin Farrell) first preparing to work, literally getting to grips with a beating heart in an open chest cavity, and then finishing up: he sheds the gown and gloves he’s been wearing, a clear disconnect from his day job but, again, only the first evidence of disconnection we see. Steven might be a great surgeon, or he might not, but however he conducts himself professionally, the stilted, almost ludicrously ineffective conversation he then shares with his anaesthetist Matthew (Bill Camp) doesn’t really suggest a man comfortable in his own skin.

At home, things are amiss too: he parrots expressions of love and fealty with his attractive but monochrome wife Anna (Nicole Kidman) and his kids, Bob and Kim, but there’s something hollowed out about it all: this is soon supported by the, shall we say, ‘niche’ tastes displayed by husband and wife when they’re alone in their bedroom. Then, there’s yet another layer of strangeness: Steven is mysteriously friends with a sixteen year old boy, Martin (Barry Keoghan). Initially, the nature of their friendship is kept in the dark. Their conversation is respectful in some ways, sinister in others: it seems that Steven has taken the apparently fatherless boy under his wing, meeting up with him to offer things like gifts and life advice, but the more he gives to Martin, the more Martin wants.

As Martin weaves his way into Steven’s life to an ever more claustrophobic degree, a situation facilitated by Steven’s apparent cluelessness about sensible boundaries and professional conduct, things feel as if they’re already on the edge of a precipice. Then, it seems as though the precipice is reached: Bob (Sunny Suljic) suddenly contracts a mysterious, paralysing illness, collapsing to the ground one day. It’s unclear whether this is a psychosomatic condition or a purely physical one. But there’s more, as the film reaches that little further to embellish its narrative, now with elements of the (arguably) supernatural escalating the tension in ways which are bleakly comic and appalling by degrees.

Although loosely based on the Greek myth of Iphigenia – hence the title – The Killing of a Sacred Deer is right up to date, and full of very modern anxieties. Medicalisation, medical procedure, professional practice, wealth inequality and bereavement; here, these things are weaponised. As presented here, accompanied by an overwhelming, atonal soundtrack, the film is a fever dream anyway, but it sticks with the theme of sacrifice, pulling the already loosely-linked Murphy family apart via its genuinely effective, creepy central performance by Keoghan. The physicality of this young actor is – with apologies to the guy – well-suited to the role. He has a sly, usually emotionless face and a voice which betrays no emotion either, no matter what he says. He comes across as deeply unpleasant, and this eventually squeezes some terror and rage out of the Murphys – Steven becomes utterly unreasonable, whilst Anna turns into a conniving nightmare.

Although loosely based on the Greek myth of Iphigenia – hence the title – The Killing of a Sacred Deer is right up to date, and full of very modern anxieties. Medicalisation, medical procedure, professional practice, wealth inequality and bereavement; here, these things are weaponised. As presented here, accompanied by an overwhelming, atonal soundtrack, the film is a fever dream anyway, but it sticks with the theme of sacrifice, pulling the already loosely-linked Murphy family apart via its genuinely effective, creepy central performance by Keoghan. The physicality of this young actor is – with apologies to the guy – well-suited to the role. He has a sly, usually emotionless face and a voice which betrays no emotion either, no matter what he says. He comes across as deeply unpleasant, and this eventually squeezes some terror and rage out of the Murphys – Steven becomes utterly unreasonable, whilst Anna turns into a conniving nightmare.

But in both cases, their extreme responses often border on black comedy. This is the effect I mentioned in the introduction, this feeling of deep unease in the laughter: there’s something quite unpleasant about laughing in spite of yourself at something you know is, at the same time, tragic. It doesn’t just happen there, either. The script’s fixation on awkward physical transitions, usually linked to adolescence but not exclusively, and on people as component body parts (we see characters kissing hands, kissing feet, spitting teeth) leads to some really unpalatable lines and sequences. Things cross into torture horror in places, then trip lightly back to farce in others.

An overbearing, nauseating but fascinating film, I am – somehow – still glad I experienced The Killing of a Sacred Deer; I also feel completely sure that it’s not a film I’ll ever want to revisit. It’s just that kind of skilful, weird experience that sticks in your mind and to your skin. I’d also say that this is not a film for everyone, and if you struggled with the sledgehammer symbolism of mother! (as I did) then this film will leave you in much the same state.

Indeed, it’s hard not to compare the two films: each disrupts logic and conventional plot developments in favour of a fantastical threat to family and personal agency; hey, perhaps our modern age is just lending itself to these wild-eyed, somewhat unreal concerns. I preferred The Killing of a Sacred Deer as a film, however, if in large part to the varied and unusual performances it drags out of its key players, from Farrell to Alicia Silverstone (!) and definitely Nicole Kidman, who is, to her credit, really getting the challenging roles lately.

The Killing of a Sacred Deer is out on general UK release now.