For many of us growing up in the Seventies and Eighties, being terrified by the Borley Rectory hauntings was practically a rite of passage. For my part, I must have been around nine years old, I’d guess, and found out about ‘the most haunted house in England’ from a Readers’ Digest Mysteries of the Unexplained compendium. There were other tales of ghostly phenomena which also fascinated and appalled me – the Matthew Manning story, the Bell Witch case – but the allegedly ghostly scrawls addressed to ‘Marianne’ really fixed themselves in my imagination. I couldn’t bring myself to re-read the section on Borley Rectory for weeks at a time, but thought about it constantly, even beginning to practise my own automatic writing after I read about its use in Borley – thus, terrifying myself even more.

For many of us growing up in the Seventies and Eighties, being terrified by the Borley Rectory hauntings was practically a rite of passage. For my part, I must have been around nine years old, I’d guess, and found out about ‘the most haunted house in England’ from a Readers’ Digest Mysteries of the Unexplained compendium. There were other tales of ghostly phenomena which also fascinated and appalled me – the Matthew Manning story, the Bell Witch case – but the allegedly ghostly scrawls addressed to ‘Marianne’ really fixed themselves in my imagination. I couldn’t bring myself to re-read the section on Borley Rectory for weeks at a time, but thought about it constantly, even beginning to practise my own automatic writing after I read about its use in Borley – thus, terrifying myself even more.

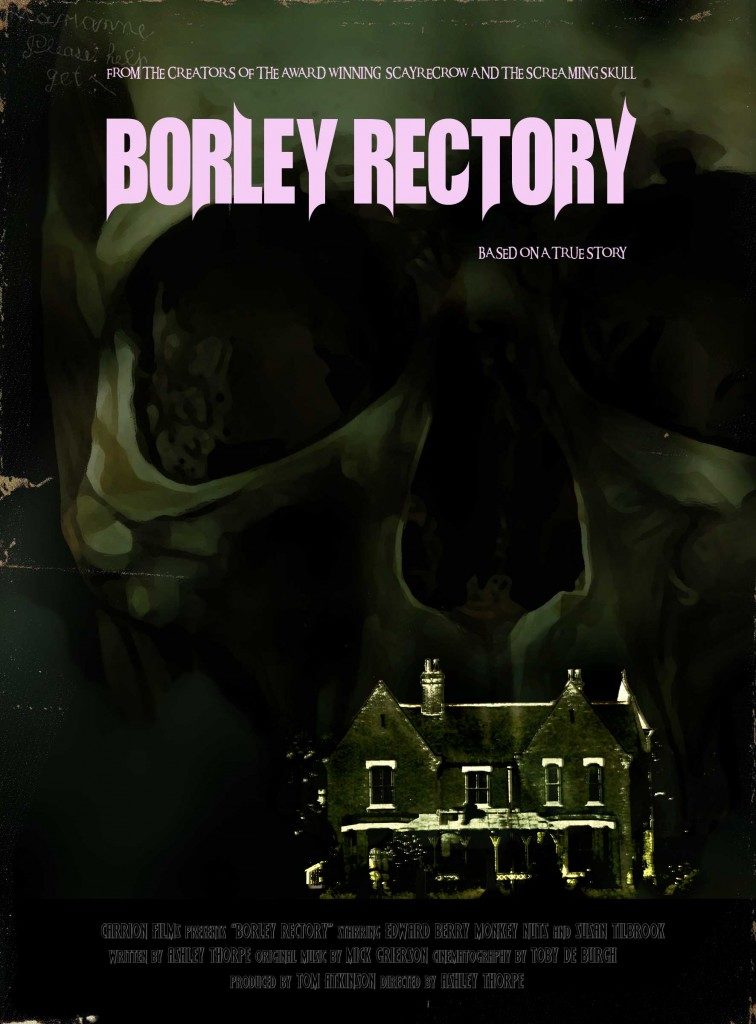

I’m clearly not alone in this; many people of around my age need only hear the phrase ‘Usborne Book of Ghosts’ and they’re off into a kind of traumatic nostalgia trip – the kind which seems uniquely beloved of horror fans, this drive towards recapturing the halcyon terrors of childhood. This makes it all the more unusual that a cinematic take on the Borley Rectory hauntings has been so long in coming, Haunting at the Rectory (2015) notwithstanding, and even if several superb haunted house movies (such as The Legend of Hell House) have already taken their cues from the case. Director Ashley Thorpe originally intended to make his Borley Rectory a short film; years have ensued, the project has grown, and the resultant film is a feature length offering.

Some sort of potted history would seem to make sense here, given the framework used in the film itself, but then the history of Borley Rectory, in Essex, England, is a convoluted, complex one. Originally built on the site during the Victorian era, the first inhabitants of the house – the Bull family – soon reported ghostly phenomena, such as footsteps, and the apparition of what seemed to be a nun, walking in the grounds. A combination of local rumours and the literary imaginations of the Bull daughters no doubt fuelled an atmosphere of suggestibility, but it seems that the people involved were very earnest about what they had seen. By the time that the Bull family vacated the living, with Harry Bull dying in the late 1920s, the rectory’s reputation was firmly established.

In 1929, Mr and Mrs Smith became the new incumbents, and the supernatural phenomena persisted; the family eventually contacted The Daily Mirror newspaper, asking for their help in contacting the Society for Psychical Research, and a series of sensationalist articles duly appeared before the newspaper facilitated the involvement of Harry Price, a notorious ‘ghost hunter’ of his day. After the Smiths left and the Foysters moved in during 1930, Price maintained his interest, and in many ways the phenomena seemed to intensify around the Foysters, particularly Mrs Marianne Foyster. Allegations of faking phenomena dogged Price throughout his professional life and Borley was no exception, but certainly Price’s involvement helped to cement a public interest in the place which has endured for the best part of a century, and after the Foysters, too, left Borley Rectory, Price and his team even took the unusual step of leasing the property for a year. Further spirit messages were communicated to members of his team during this time, including the prophecy that the Rectory would soon burn to the ground: this it did, in 1939, with at least one witness claiming to have seen a ghostly nun at an upstairs window…

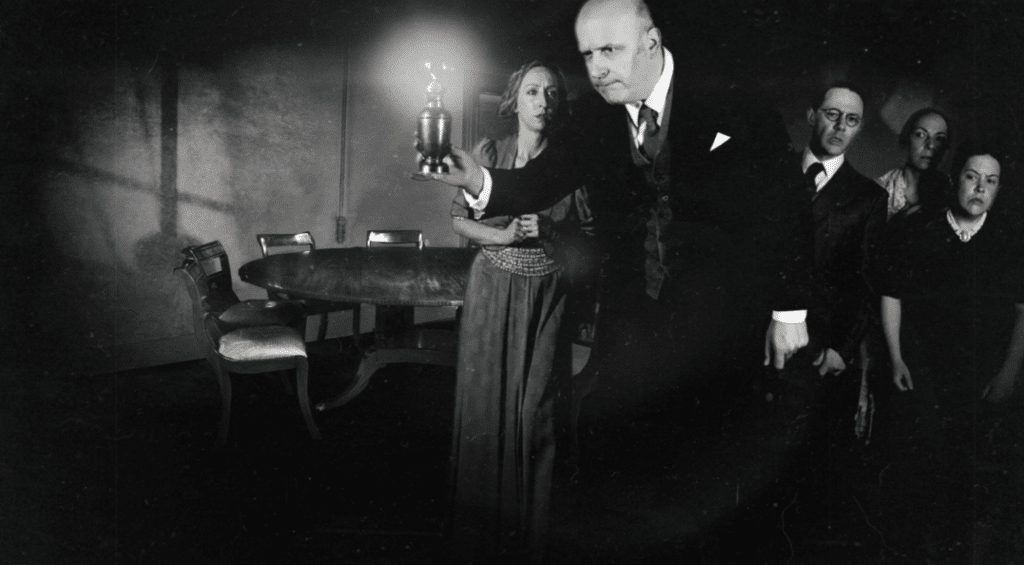

Borley Rectory (2017) is unusually framed as a documentary film, exploring and discussing the events mentioned above in largely linear order with the help of a narrator – none other than Julian Sands. Ashley Thorpe explained at the screening that his film had been heavily influenced by his own childhood nostalgia for spooky 70s TV, such as the works of Lawrence Gordon Clark and the Armchair Thriller series, which had a scary ghost nun of its own. I’m sure I saw some Ghost Story for Christmas artwork tucked away in one of the sequences, too. However, Thorpe also mentioned a love of 1920s and 30s Hollywood horror, which seems altogether heavier in the mix: Borley Rectory is shot entirely in black and white, and the actors wear the heavily stylised costumes and make-up beloved of, say, early James Whale cinema. Whilst it’s somewhat engaging to see some well-beloved actors both dressed in period costume and acting accordingly – with Reece Shearsmith as the Daily Mirror reporter, Nicholas Vince as Reverend Smith and author Jonathan Rigby as Price himself, the rather studied delivery somewhat dwarfs any stylistic links to the barely-glimpsed horrors of Gordon Clark.

Borley Rectory (2017) is unusually framed as a documentary film, exploring and discussing the events mentioned above in largely linear order with the help of a narrator – none other than Julian Sands. Ashley Thorpe explained at the screening that his film had been heavily influenced by his own childhood nostalgia for spooky 70s TV, such as the works of Lawrence Gordon Clark and the Armchair Thriller series, which had a scary ghost nun of its own. I’m sure I saw some Ghost Story for Christmas artwork tucked away in one of the sequences, too. However, Thorpe also mentioned a love of 1920s and 30s Hollywood horror, which seems altogether heavier in the mix: Borley Rectory is shot entirely in black and white, and the actors wear the heavily stylised costumes and make-up beloved of, say, early James Whale cinema. Whilst it’s somewhat engaging to see some well-beloved actors both dressed in period costume and acting accordingly – with Reece Shearsmith as the Daily Mirror reporter, Nicholas Vince as Reverend Smith and author Jonathan Rigby as Price himself, the rather studied delivery somewhat dwarfs any stylistic links to the barely-glimpsed horrors of Gordon Clark.

This brings me to my biggest gripe with Borley Rectory, something concomitant with the chosen acting approach. It’s the animation. Rather than a conventional shoot, the film was shot entirely on green-screen and then pieced together; the actors themselves were never shot on any location, it was all done and dusted in a few days, and then the film was built around them. I don’t doubt that this is a meticulous process, and doubly so for sequences such as the pop-up book, which I acknowledge was built on the back of careful research and application. I also know that there are other forces at work and other considerations to be made in judging how best to put a film together, made all the more difficult by the vastness of the Borley history. Some viewers may love this painstaking approach. However, the effect for me was to make me feel doubly distanced from the events taking place on screen. An altogether quieter, more conventional framework would, I feel, have better served the story. The ambition here is clear, but ultimately, the flashy visuals engulfed the haunting.

That all aside, it was certainly enjoyable to see something so oddly beloved finally make the leap from the printed page to the screen. Perhaps the most salient point which Borley Rectory successfully communicates, is that a haunting seems to be very much like a relationship; people, with all of their flaws and ulterior motives, imprint upon the phenomena they report; in some cases, their flaws make the phenomena altogether. This is one of the most confounding but fascinating aspects to any alleged haunting, and Borley Rectory – the place – seems to have been an example of this par excellence. It’s fitting that Borley Rectory – the film – successfully makes this point, whatever my misgivings about its visual style.