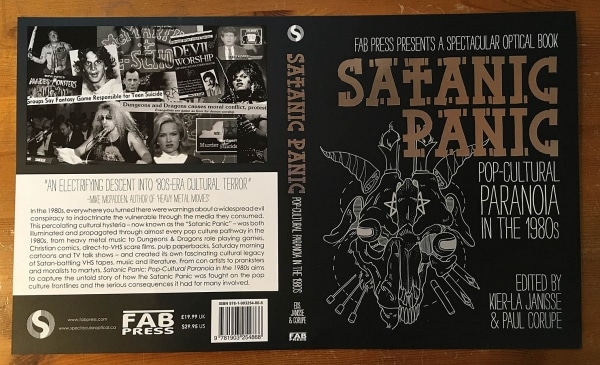

The so-called ‘Satanic Panic’ of the Eighties (with some fallout in the following decade) is a curious phenomenon – one born out of a collision of new media, psychiatry, pop-psychiatry and pop culture. It’s one of those things which could – and did – run and run, borne aloft by its ‘hidden’ status (how do you disprove a secret?) and of course its seductive promise of illicit sex, cult activity, crime and murder – all available for concerned parties to enjoy, whilst simultaneously fretting and disdaining it all, of course. Various theses and books on the subject have appeared piecemeal over the years, but never before has there been such an exhaustive examination of the phenomenon as offered by the recent FAB Press release Satanic Panic – a book which brings together a number of commentators and invites them to offer their expertise on the topic in their own particular styles and from their own perspectives.

The so-called ‘Satanic Panic’ of the Eighties (with some fallout in the following decade) is a curious phenomenon – one born out of a collision of new media, psychiatry, pop-psychiatry and pop culture. It’s one of those things which could – and did – run and run, borne aloft by its ‘hidden’ status (how do you disprove a secret?) and of course its seductive promise of illicit sex, cult activity, crime and murder – all available for concerned parties to enjoy, whilst simultaneously fretting and disdaining it all, of course. Various theses and books on the subject have appeared piecemeal over the years, but never before has there been such an exhaustive examination of the phenomenon as offered by the recent FAB Press release Satanic Panic – a book which brings together a number of commentators and invites them to offer their expertise on the topic in their own particular styles and from their own perspectives.

The tone is set by editor Kier-La Janisse, who makes some good points contextualising the Satanic Panic hooey via her rundown of the rise of suburban occultism during the 70s, added to by changing home lives which affected teenagers; the rise of the ‘latch-key kid’ provided ample opportunity for worried parents and neighbours to wonder just what the hell these kids were getting up to. This material is quite weighty with Janisse’s own personal confessions about her own past situations – which, personally, made me feel a little awkward, as if someone was blurting out details of their own traumas mid-way through an otherwise neutral conversation. However, Janisse makes a very interesting key point elsewhere here, and one which is echoed by Adrian Mack at the end of the book: just because we can safely debunk one conspiracy theory, doesn’t mean that there are none, and successfully identifying one fertile seam of bullshit does not mean that we are immune to bullshit ever after. It’s an important element of context here and a point which definitely deserved to be made.

A foreword by Feral House’s Adam Palfrey is a charming entry in the book – Palfrey is a lively but self-critical man who discusses his work with Church of Satan’s Anton La Vey (whose daughter, you may well have seen, mounted a brave but unfortunately hobbled defence of her father’s church on the chat show host Geraldo’s special episode, ‘Exposing Satan’s Underground’). Palfrey clearly liked and respected La Vey, and correctly, I think, identified him as a nostalgist: many of his followers seem to adopt La Vey’s beloved mores but forget that he had molded his own world to his own predilections.

The first key chapter returns to what is probably the beginning of the whole debacle and therefore vital here: Michelle Remembers, a cod-psychological study of a woman (later the psychiatrist’s wife!) in which the doctor in question, Lawrence Pazder, uncovered memories of Michelle’s ritual abuse. I have to confess here, I’ve never read this book, though I’m aware of it from secondary sources; this maybe meant the material from Michelle Remembers taking on an even stranger air when refracted through a different, and far more sceptical medium – the chapter written by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas. The examination of Smith’s believability was very interesting, comments on the anti-female bias of Michelle Remembers are compellingly made, but perhaps the key point is in the questions which go unanswered here: why did Smith relate this ‘history’? And if it has a nub of truth in it (perhaps some real trauma in her background) then why did a professedly-secular woman and her therapist go so far in the direction of their claims?

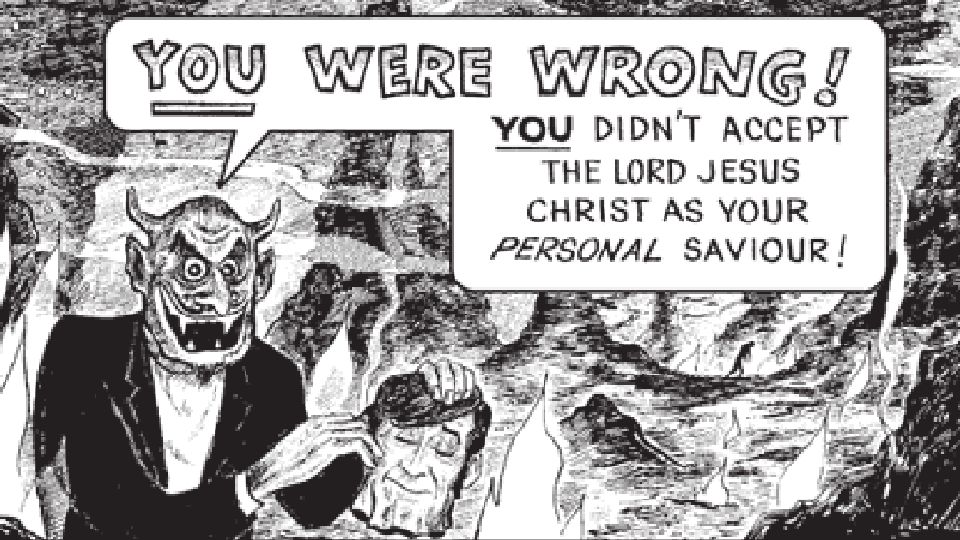

Of the remaining chapters, several stand out – often tonally very different, but amusing and entertaining by turns. I enjoyed several particularly. Alison Nastasi’s take on trash occult novellas was engaging, taking a broadly tolerant view of the publications named, albeit with some well-reasoned context. Joshua Benjamin Graham’s appraisal of Christian Fundamentalist spins on 80s cartoons (such as He-Man!) is joyous and pithy good fun, as well as effortless in how it lampoons loons and paints a vivid picture of those contemporary concerns. Kevin L. Ferguson’s rundown of the relationship between the devil and then-new technology is very informative and links in with some old favourite films such as Evilspeak, though veers into slightly academic terrain at times, or else a longer project waiting to happen. Then, Alison Lang’s debunking of the aforementioned Geraldo Rivera’s ‘Satanic Special’ is wonderful (her quote regarding the episode – “its hysteria is both deeply hilarious and troubling in its amped-up ignorance” – could really make a good epitaph for Geraldo’s whole series) and similarly, Liisa Ladouceur’s even-handed words on the PMRC represent just how head-scratching their whole ethos was, whilst Samm Deighan’s savvy chapter on heavy metal and the movies picks up on probably one of the most fun relationships in horror. There’s plenty of other interesting material here, too. You can feast your eyes on anything from Christian metal band Stryper, to the recently-deceased fundie cartoonist Jack Chick; reading about the baiting of Bob Larson made me laugh a lot. Oh, and I could hardly pass on David Flint’s perceptive rundown of that frenetic eccentric Genesis P. Orridge and his treatment at the hands of the British establishment…

As in any array of chapters as broad as these, I did hit a couple of snags with the book. I think the main one of these is repetition; if you dip in and out of Satanic Panic, as I imagine many people will, then this won’t be such a problem. However, if you read the book from beginning to end – again, as surely many people will – then you find yourself reading about the same thing several times, such as variants on the fact that Michelle Remembers was debunked. These mentions make perfect sense within their own chapter and the approach taken by the editors has clearly been to allow each writer a great deal of freedom – which is possibly why bibliographies/references are different for each chapter, or absent – but, overall, reading the same information is a minor irritation. I also couldn’t help but feel that the Ricky Kasso chapter (‘All Hail the Acid King’) was meandering and list-heavy, with some clumsy wording (if something is offhand described as ‘grotesquely masculine’, then I feel that needs explanation.)

However, these gripes are minor in comparison with the rest of the well-researched and thought-provoking content through this book. For the absolute most part, the authors’ investment and knowledge comes through via the quality of writing on offer – alongside rare artwork, posters and stills, making this book yet another FAB Press two-fingers-up to e-books and a delight to leaf through. I read new perspectives on things I knew about, and took away plenty I’d never encountered – which is probably one of the highest compliments I can pay. It’s also, to an extent however, a sobering book: for all the fun along the way, the point is made that these kinds of witch-hunts have not gone away, could recur in future, and nor have we rid ourselves of the kind of organised abuse which believers in Satanic influence were so certain was there thirty years ago. It was and is there – it’s just that, when it comes to light, Satan seems dubious by his absence.

You can buy a copy of Satanic Panic in paperback or hardback – now on sale! – here.