Memory is something sinister and not to be trusted in Parallax (2020) – an unusual, character-centred story which admittedly takes a while to get going, but when it does, it goes somewhere very interesting indeed.

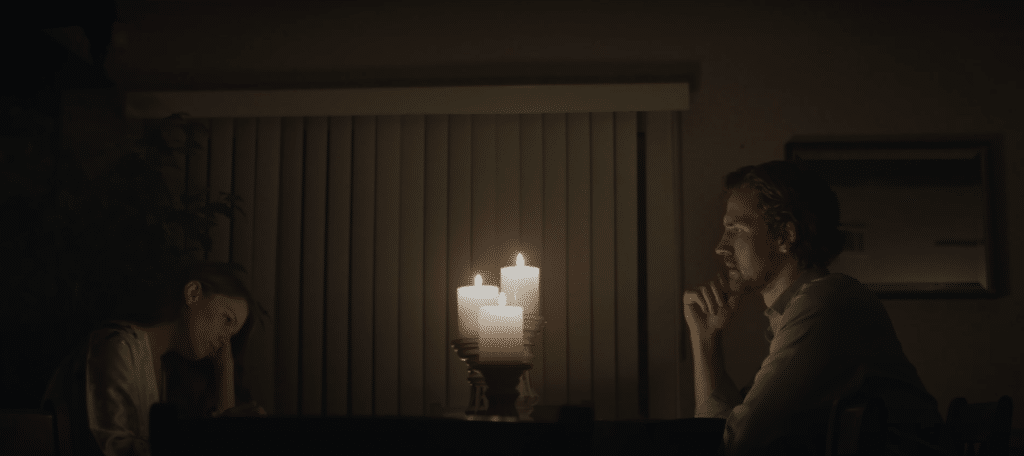

Selfhood is offered as a theme straight away: via a dispassionate voiceover, a young woman called Naomi (Naomi Prentice) begins explaining her anxieties over, seemingly, belonging to a world she no longer recognises. Her relationship with fiance Lucas (Nelson Ritthaler) is understandably suffering beneath the weight of this; he tries to play normal around her reported feelings of dissociation, but in truth, he’s pouring his heart out about her to his counsellor. Meanwhile, Naomi’s behaviour gets more erratic: she very nearly tests her thesis that she exists in a waking dream by drowning in the bathtub, only just being saved in time.

So, is this just a traumatised young woman, having a glorified breakdown? Lucas begins doing what he can to piece Naomi’s history together, realising that he knows comparatively little about her previous life. And, had the film stuck with this narrative, I think it would have suffered overall. Parallax’s genre is not immediately apparent from what you see in the first act, and it seems therefore to be operating as an allegory for mental illness – or, dementia, something else which is raised as a possibility, as Naomi and Lucas seek medical help for her condition. These early sequences, which use a combination of stilted conversations, voiceover and often oppressive interior spaces, soon come to feel quite oppressive. The metaphor of the sea, or of drowning, adds to this sense of weight. However, the sea is soon being used as a source of liberation, too. Through her paintings, Naomi begins to hallucinate that she is at the beach, and these moments of escapism lend the film a much-welcomed respite too, adding natural light and landscape. The emphasis and style of the film begin to shift.

At this point, the film also begins to break free of its seeming focus on mental illness. When Naomi begins to see, and interact with someone else on the ‘beach’ and in other apparently hallucinatory places, Parallax shifts up a gear, turning into a mystery to solve, one which gradually hands its key clues over to the audience. In some respects like Mulholland Drive – another film where the mystery is turned over to viewers – and in some respects Aronofsky-style experimentation with what different mental states mean and how they can be represented through various imagery, it would be very difficult to predict with confidence where the story will go, and that it very much to the credit of writer/director Michael Bachochin. Parallax’s grand ambitions do mean that a lot of the plot occurs in the last thirty minutes; even without this, though, the story can feel disorientating by its nature, dealing as it does in questions about self, memory, certainty and symbolism. And, as adventurous sci-fi elements begin to come into play, the narrative never loses sight of Naomi and the sympathy she deserves, as she struggles to make sense of her divided self.

Another allegory for ‘living a lie’ in some respect would have just been another allegorical film in a long line of them, but Parallax does far more than that. When it really begins to unfold and move in new directions, it rewards your attention. Above all, it has a clear sense of aspiration, and that really does mark it apart from a whole host of other indie movie projects.

Parallax (2020) receives a limited US theatrical run from 10th July.