When I heard that Mara was a horror story invoking sleep paralysis as a key element of its plot, as a sufferer I was immediately interested. Sleep paralysis is well understood in the modern age, just as sleep and dreams are generally, but anyone who has ever had a significant nightmare, or a waking nightmare will know that reason and rationality are furthest from your mind when undergoing this kind of terror; therefore, these experiences remain ripe for solid on-screen explorations, offering lots of potential. Happily, director Clive Tonge and writer Jonathan Frank have shown themselves more than up to that task in Mara, a film which weaves a mythology around sleep paralysis, but balances this against far more grounded and mundane preoccupations which trouble people in their sleep.

When I heard that Mara was a horror story invoking sleep paralysis as a key element of its plot, as a sufferer I was immediately interested. Sleep paralysis is well understood in the modern age, just as sleep and dreams are generally, but anyone who has ever had a significant nightmare, or a waking nightmare will know that reason and rationality are furthest from your mind when undergoing this kind of terror; therefore, these experiences remain ripe for solid on-screen explorations, offering lots of potential. Happily, director Clive Tonge and writer Jonathan Frank have shown themselves more than up to that task in Mara, a film which weaves a mythology around sleep paralysis, but balances this against far more grounded and mundane preoccupations which trouble people in their sleep.

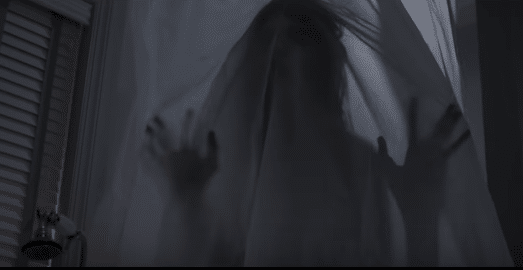

The film begins with a child, Sophie Wynsfield, who is woken one night by strange sounds. She investigates, looking for her mother, but when she finds her she also finds her father, lying dead, frozen in terror in his bed. Mother Helena is soon charged with his murder as the only possible suspect who had access to him that evening. Images of the ‘night hag’ which then appear during the opening credits help to forge the link between what we now acknowledge as night terrors with something more purposeful and malign. Many cultures around the world have personified this kind of nightmare as a hag, spirit or demon, in keeping with a common symptom of the experience, the sensation of something (or therefore someone) pressing down on you and restricting your breathing. With this as context, we meet our main character, Dr. Kate Fuller (Olga Kurylenko), a rookie psychologist called in by the police to help deal with this complex case. She tries to win the terrified Sophie’s trust, and for the first time, as psychologist and child speak about the events of the night before, Sophie mentions a name – ‘Mara’.

When Helena is later interviewed, she also invokes the name Mara, referring to it as a ‘sleep demon’ and the real murderer of her husband. Perhaps it’s her immersion in the case, but Kate, too, now begins to experience unsettling waking dreams as she begins to piece together whatever she can about this strange case. Using the scrawled notes she found at the scene, she investigates further, coming into contact with more and more people who believe that their sleep is being disturbed by this sleep demon. In particular, an attendee of a support group by the name of Dougie suggests that he knows how Mara operates, and can predict what she will do next – and to whom. Naturally law enforcement aren’t much taken by this kind of supernatural explanation for deaths like Matthew Wynsfield’s, and Dougie’s involvement with a now growing list of premature deaths puts him in the frame. To clear his name, he has to reveal to Kate what he knows. By this stage, Kate is herself embroiled in something she cannot understand, or escape.

From the outset, Dr. Fuller seems to have a strange, borderline unprofessional level of interest in the Wynsfield case, throwing out promises to Sophie which she must know she cannot keep. This suggests trauma lurking in her own background, even from the very beginning of the film. Kurylenko, in a decidedly unglamorous and challenging role, plays her part with a suitable blend of self-contained gravitas and moments of barely-repressed emotion. The film as a whole depends very much on her, her responses and impressions; as her own back story comes to the fore, her focus on the case makes additional sense; she also attracts more sympathy, as hers is a troubled lot. The sleep paralysis scenes themselves are also very effective. Sheer helplessness is communicated simply but plausibly, and the escalating horror is successful because the director understands that the supernatural belongs on the periphery; some of the most unsettling scenes are barely there at all, but they make your skin crawl nonetheless.

Something else which is very interesting in this film comes via another of its core plot developments – that Matthew Wynsfield somehow puts himself in danger by seeking help for his sleep paralysis issues. Rather than that vague modern panacea of ‘support’ ridding people of their problems, here in the form of a support group, in Mara it exposes people to more harm. In effect, a potential cure, one we believe in on an almost religious scale today, lays people bare to a threat, which itself stems from an innovative blend of folklore, the supernatural, and something between a good old-fashioned curse and psychological breakdown. It’s pessimistic in the extreme, and it’s handled with genuine ingenuity here.

Something else which is very interesting in this film comes via another of its core plot developments – that Matthew Wynsfield somehow puts himself in danger by seeking help for his sleep paralysis issues. Rather than that vague modern panacea of ‘support’ ridding people of their problems, here in the form of a support group, in Mara it exposes people to more harm. In effect, a potential cure, one we believe in on an almost religious scale today, lays people bare to a threat, which itself stems from an innovative blend of folklore, the supernatural, and something between a good old-fashioned curse and psychological breakdown. It’s pessimistic in the extreme, and it’s handled with genuine ingenuity here.

Whilst sleep has been used as the basis for horror many times in horror cinema – something which the film acknowledges and openly alludes to by namechecking Freddy Krueger at one point – Mara is an altogether different animal. This is a very, very slow-burn movie, taking its time and allowing the sensation of inescapable, ratcheting tension to pervade. A range of effective performances underpin this throughout, with special mention to horror monster diehard Javier Botet and Kurylenko has just the right degree of vulnerability set against strength, a modern woman struggling to recast events in safe, predictable scientific language. Carefully paced and moving deliberately throughout, it captures sleep paralysis well, weaving elements of mythology around it and keeping us guessing. Supernatural horror, shorn of the endless jump scares, is so much more worthy of time and attention, as Mara shows in abundance. It’s clever, brooding and hideously effective.

Mara (2018) will be released in US cinemas on September 7th 2018.