The Spanish director Eloy de la Iglesia is a mercurial, intriguing figure. His work has long been underappreciated, neglected, or simply misunderstood – amongst both Spanish audiences and English-speaking cinephiles. Severin Films are remedying this with several Blu-ray releases of de la Iglesia’s pictures, including his most (in)famous – and arguably, for many years, his most deeply misunderstood film – Cannibal Man (or Le semana del asesino).

An outspoken, openly gay socialist, director Eloy de la Iglesia’s early career seems like something of an anathema in the context of General Franco’s Spain. The filmmaker’s feature debut was a portmanteau children’s film, Fantasia… 3(1966), produced at a time when family-oriented features attracted significant funding from the Spanish government. However, de la Iglesia’s name, at least amongst English-speaking cinephiles, is largely remembered for a core group of genre films from the early 1970s – from thrillers such as The Glass Ceiling (El techo de cristal, 1971) to the hugely underrated Clockwork Orange pastiche Clockwork Terror (Una gota de sangre para morir amando / Murder in a Blue World, 1973). (Seriously, I could write a thesis on Clockwork Terror: hit me up!)

From the mid-1970s, with the death of Franco and the liberalisation of Spanish culture (and film censorship), de la Iglesia made films that were more openly political, often focusing on youth subcultures – with which de la Iglesia had an apparently Pasolini-like fascination. In the 1980s, de la Iglesia made El pico (The Needle, 1983) and its sequel (El pico 2, 1984): both films dealt with delinquency and addiction. At around the same time, the director himself developed a heroin habit which accompanied, and most likely exacerbated, a slump in his career, before a major retrospective in the mid-90s revived interest in his work. His final film, in 2003 (Bulgarian Lovers / Los novios búlgaros), was produced after a 16 year hiatus from cinema.

Made amidst two distinctive thrillers that de la Iglesia directed (The Glass Ceiling and No One Heard the Scream / Nadie oyó gritar, 1973), Cannibal Man sits apart from them in the sense that it continuously attempts to negate more traditional models of suspense, its narrative focusing on a cycle of violence that feels utterly inevitable in the manner in which it escalates. What results is a film that feels profoundly bleak, the acts of brutality – motivated by desperation rather than cruelty – escalating and threatening to spill over the edges of the film frame. Notably, when Cannibal Man’s script was first submitted to (and rejected by) the Spanish censors, it was classified as ‘horror’ owing to the ‘accumulation of crimes and blood’ within it[i]. In the midst of the film’s violence is the protagonist, Marcos (Vicente Parra), who is ‘forced’ to commit murder after murder in order to cover up the accidental killing of a taxi driver.

As Cannibal Man opens, Marcos (Vicente Parra), a slaughterhouse worker, lives in a run-down shack near a modern high-rise building. Marcos is pursued romantically by Rosa (Vicky Lagos), the waitress in the café that Marcos frequents; but Marcos is involved with a significantly younger girlfriend, Paula (Emma Cohen).

One Sunday evening, Marcos and Paula become involved in an argument with a taxi driver, who takes umbrage at their heavy petting in the backseat of his car. Marcos strikes the taxi driver with a rock, accidentally killing him. On Monday, when Paula suggests they should go to the police, Marcos strangles her and puts her body under his bed.

On Tuesday, Marcos’ brother Esteban (Charly Bravo), a truck driver, returns home earlier than expected. (He and Marcos live together.) Marcos confides in Esteban, but Esteban refuses to assist Marco. (‘If you won’t help me, who will?’, Marcos wonders.) Marcos kills Esteban by bashing his skull in with a wrench, and hides the body in the bedroom with Paula’s corpse.

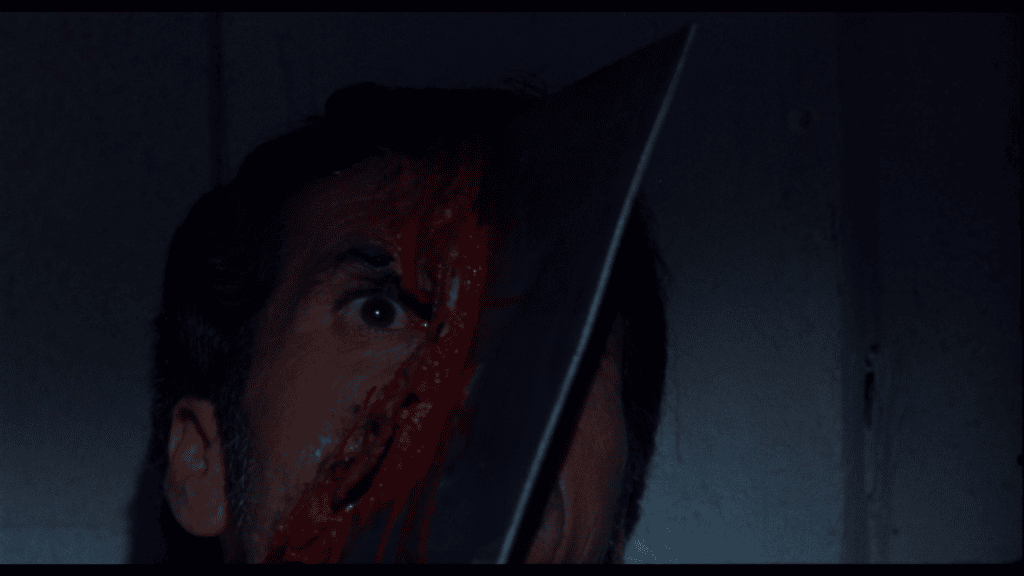

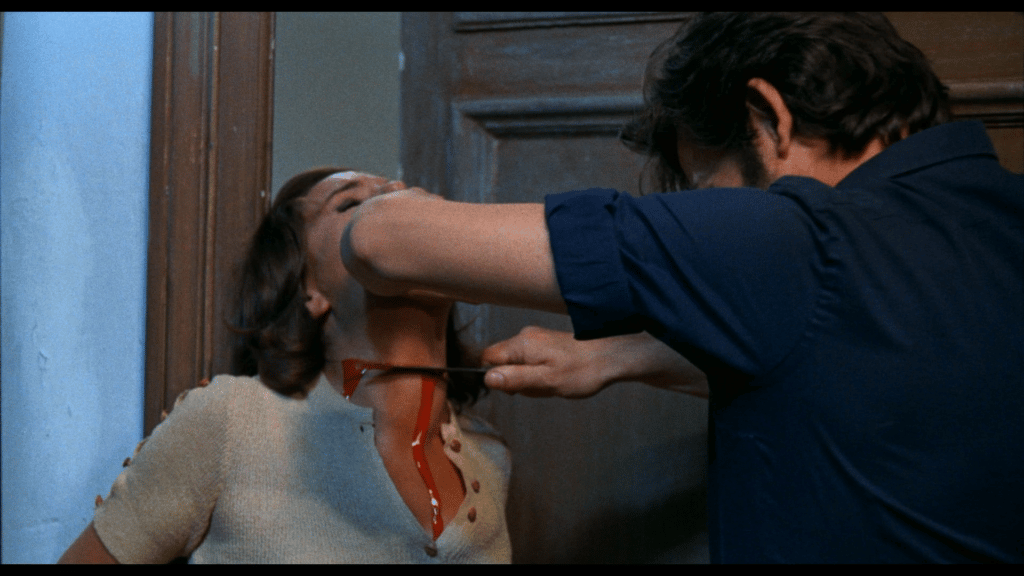

Wednesday: Esteban’s fiancée Carmen (Lola Herrera) arrives, looking for her lover. She discovers the corpses of Esteban and Paula, and Marcos slits her throat with a carving knife. On Thursday, Carmen’s father, Mr Ambrosio (Fernando Sanchez Polak), knocks on Marcos’ door, searching for his daughter. When Ambrosio discovers the bodies of Carmen and Esteban in bed together, in a perverse mockery of the marital bed, Marcos kills Ambrosio by burying a cleaver in his face.

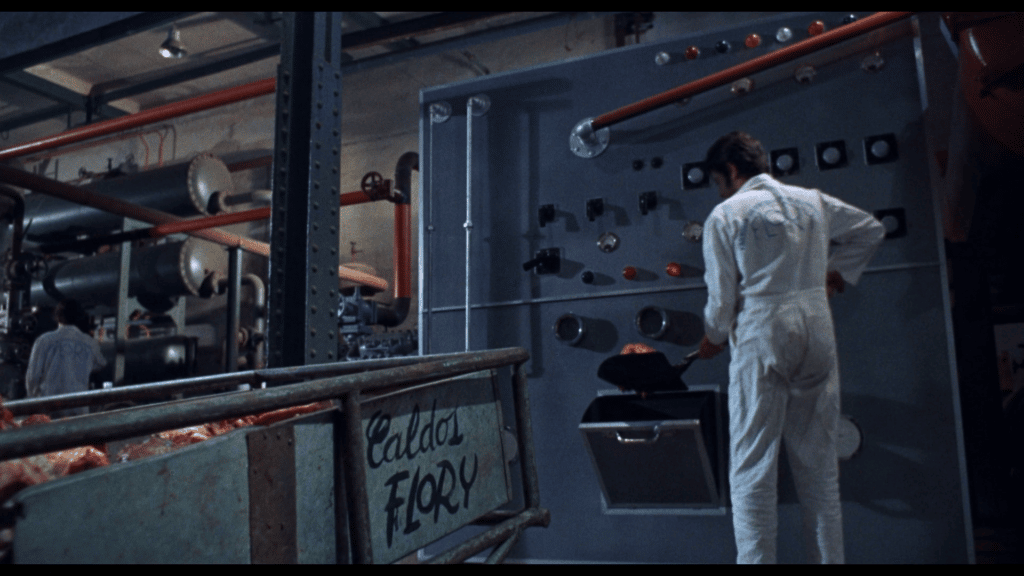

In the midst of this chaos, Marcos is given a promotion at the factory: he is commanded to operate a huge, computerised meat mincer, which is sold as the future of the industry. Operating this machine, Marcos sees an opportunity to dispose of the corpses that are littering his home, and sets about dismantling them with a saw in his shack, and carrying the parts to work in a bowling bag in order to feed them into the mincer.

Meanwhile, in a flat on one of the upper floors of the nearby high-rise building, a wealthy young man, Nestor (Eusebio Poncela), has been watching the events unfolding in Marcos’ shack with an erotic fascination.

The script for Cannibal Man was originally submitted to the Spanish censors under the title Auténtico caldo de cultivo, which translates as ‘Genuine Breeding Ground’ – presumably, a breeding ground of violence and brutality. (One may speak of a ‘breeding ground’ of a destructive ideology: a caldo de cultivo del fascismo, for example.) However, the script was rejected. Unfortunately, days before this decision was reached, production had already begun – illicitly. Subsequently, the filmmakers were forced to hastily revise the script, and resubmit it to the Spanish censors a month later, under the title Le semana del asesino – only for it to be rejected once again. A third pass at the censor was made; production continued with this new script in place.

Sticking points for the Spanish censors were the film’s scenes of violence and the implicit homosexuality of the characters. This implicit homosexuality was made very explicit in an early cut of the film, which featured Marcos and Nestor in, for want of a better phrase, a passionate snog, complete with circling camerawork: this footage, deleted from the film’s final edit, is featured as a silent outtake on this Blu-ray release, alongside other footage excised from the finished picture. (Poetically, the scene would have echoed the heavy petting of Marcos and Paula in the cab, and the more functional bout of coitus that Marcos and Rosa participate in.)

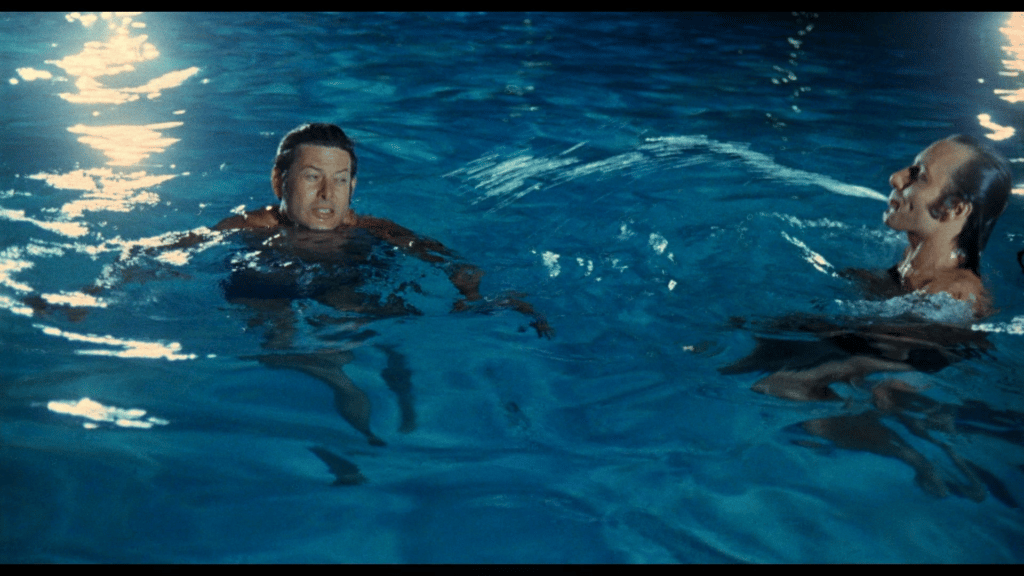

Three of the principals involved in the film were gay: de la Iglesia, and actors Vicente Parra and Eusebio Poncela. Parra seems to have been conflicted about his sexuality and ‘closeted’, largely owing to roles which positioned him as a heart throb for female audiences. These tensions seem to work their way into the film, with Marcos’ apparent Latin ‘machismo’ – his dalliances with his significantly younger girlfriend, Paula, and with the sultry proletarian waitress Rosa – being undercut by his encounters with Nestor, culminating in the sequence in which Nestor takes Marcos swimming at night in the pool of the club to which Nestor belongs. The pair frolic in the water like lovers, an underwater shot of the two reinforcing the sexual ‘chemistry’ of their pairing. Nevertheless, with the excising of the aforementioned scene in which Marcos and Nestor engage in tonsil tennis, the sexual tension that exists between these two characters remains buried (albeit fairly close to the surface) in the final version of the picture.

Originally, Marcos and Nestor were to have been much younger – in their late teens. However, in the interview on this disc, film critic Carlos Aguilar – who came to know de la Iglesia during his final years – says that the suggestion of a gay relationship between two young men of that age was considered taboo, so the characters were made significantly older, and when the final version of the script was submitted to the censors, de la Iglesia added a disclaimer about Nestor’s sexuality: ‘There is not the slightest hint of homosexuality in Nestor’, this disclaimer told the censor, adding that the note was added to the script ‘to avoid any possible confusion and misrepresentations concerning the behaviour of the character’[ii]. The finished film was not released in Spain until 1974, and at that time it was subjected to 62 cuts by the national censors (though some sources claim that even more cuts were made). These cuts were to reduce moments of violence and sexuality; the censor also stipulated that the film must end with the punishment of Marcos, and the final version of the film ends with a scene in which Marcos telephones the police and waits outside his shack for them to arrive. (The original, intended ending was apparently far more ambiguous.)

When talking about thrillers, comparisons with Alfred Hitchcock are often lazy and all too convenient, but nevertheless Cannibal Man seems to be driven by a very overt love of Hitchcock’s American thrillers. The opening sequence (of the Spanish version, at least: the export cut opens with some of the slaughterhouse footage spliced in before the credits) features the juxtaposition of the ultra-modern high-rise in which Nestor lives and the nearby proletarian shack that is Marcos’ home. The camera pans from the high-rise to Marcos’ shack, with a series of pull-ins to the shack, dissolves, and a dolly in to the doorway of Marcos’ home. Dissolve to an interior shot of the house, as Marcos listens to the radio and glances at the nudie pics on his wall. He reclines in a chair. (There is a clear suggestion that he is masturbating.) Cut to: Nestor in the tower block, using binoculars to spy on Nestor through the skylight in Marcos’ house.

The slow pull-in to Nestor’s shack, with the dissolve marking the transition from the exterior to the interior, seems intentionally to quote the opening sequence of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) – with its similar transition to the interior of the hotel room in which Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is involve in a sexual tryst with her married lover, Sam Loomis (John Gavin). The sexual confusion of Marcos, subtly revealed as the narrative develops, perhaps also has parallels in Psycho’s depiction of Norman Bates’ sexual repression, and sublimation of this into violence: as Carlos Aguilar says in the extra features on this disc, the people Marcos murders represent various agents of repression – economic, sexual, familial, and social pressures. Paula criticises Marcos because she believes he is not ambitious enough, too happy with his proletarian existence, and she wants him to earn more so that they may marry: he strangles her not when she suggests going to the police about the death of the taxi driver, but when she spits at him, ‘After all, you just want to live in this shack and continue being a worker all your life!’ Rosa criticises Marcos’ relationship with the younger Paula, suggesting that he should pursue a more mature woman (i.e., herself); and so on.

Meanwhile, Nestor’s use of the binoculars to spy on his neighbour – and his ‘accidental’ witnessing of the murders Marcos commits – seems deliberately to invite comparisons with Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). De la Iglesia’s previous film, the thriller The Glass Ceiling, had touched on the theme of voyeurism, the character of Ricardo (Dean Selmier) suggesting that cinema and photography are ‘an escape valve for this voyeur instinct’; but in Cannibal Man, de la Iglesia makes voyeurism a core element within the film’s oblique examination of social, economic, and sexual inequalities. Clearly drawing on the premise of Rear Window, Cannibal Man frames Nestor as a voyeur and accidental witness to murder.

From his luxurious apartment in the modern high-rise building, Nestor uses his binoculars to spy on Marcos through the skylight of Marcos’ shack: in the aforementioned opening scene, Nestor watches as Marcos masturbates to the posters of pin-up girls that adorn the walls of the shack’s measly living room – another expression of the voyeuristic / scopophilic instinct. Nestor is distanced – socially and economically – from Marcos, but is able to monitor Marcos’ activities using a symbol of his wealth: the binoculars. It is through these binoculars that Nestor witnesses some of the murders Marcos commits, and subsequently Nestor breaks down the barriers between the watcher and the watched by staging a series of ‘chance’ encounters with Marcos – eventually leading to the two men becoming friends / lovers, Nestor attempting to help Marcos escape from the cycle of escalating violence in which he has become trapped. The social difference between Marcos and Nestor is allied with the sexuality of the two characters: Nestor, from a comfortably bourgeois existence, seems quite openly to be gay, but the proletarian Marcos seems to have sublimated and repressed his homosexuality to the extent of extending his machismo through the acquisition of a much younger ‘trophy’ girlfriend. (Marcos’ truck-driving brother Esteban is an equally macho character: his fiancée, Carmen, refers to Esteban as a ‘hooligan’ and a ‘brute’, dryly commenting on their upcoming wedding that ‘At least I’ll get some jewellery’.)

When Marcos and Nestor encounter one another outside Marcos’ shack, Nestor wonders why Marcos always addresses him formally: the answer to seems clearly to be that Marcos considers Nestor to be his social better. In a later scene, Nestor tells Marcos that he plans to let his dog roam free at night, because his dog is looking for a bitch in heat. Marcos tells Nestor that all the local dogs are stray mongrels, not pedigrees – a metaphor for the class difference in the relationship between Marcos and Nestor themselves – and asks if Nestor is worried that his dog may be killed by the others. ‘I’m not worried’, Nestor tells Marcos, ‘A well-fed animal is always stronger’. (This, again, seems to be a metaphor for the relationship between Nestor and Marcos: that Nestor, thanks to his bourgeois upbringing, possesses a greater sense of emotional resilience.) When Marcos asks Nestor why the young man is so interested in him and must instead have numerous important friends, Nestor comments that ‘Important people are very boring. They have solutions for everything’.

The violence that Marcos enacts is offset by the graphic footage of animals being killed in the slaughterhouse in which Marcos works. We see beeves being strung up, their throats slit and their bodies convulsing as their blood spills out on the stone floor. Carcasses are bisected with cleavers; blood is washed down drains. The sense of desensitisation that this engenders amongst the slaughterhouse workers is communicated in a scene in which we see Marcos snacking on his sandwiches with the bloody slaughterhouse behind him. The use of documentary footage of the slaughterhouse – integrated into the naturalistic, verité-style photography of the rest of Cannibal Man – as a counterpoint to the main narrative recalls, intentionally or otherwise, Georges Franju’s 1949 short film ‘Le sang des bêtes’, in which Franju cuts graphic documentary footage of the operation of an abattoir against shots of normal life occurring in the streets of Paris. (Franju once said that the black-and-white footage of the slaughterhouse in ‘Le sang des bêtes’ would be too repulsive if presented in colour: Cannibal Man is arguably a testament to the veracity of this statement.)

The slaughterhouse is a symbol of a system that oppresses and mangles its inhabitants. As the narrative progresses, Marcos’ shack becomes itself a veritable slaughterhouse, with bodies piling up in the bedroom as each day passes – so much so that Marcos is forced to sleep on the sofa in the living room. The effect of this is articulated on the film’s soundtrack, via the sound of buzzing flies which accumulates as the story develops and the bodies presumably begin to decay.

When Marcos is ‘promoted’ to operating the huge computerised mincing machine – the only slightly absurd element in a film that is dominated by a profound naturalism – which is sold as a symbol of the inevitable future, this is in effect a ‘de-skilling’ that marks him for mockery amongst his peers – but it provides him with an opportunity to dispose of the corpses in his house. ‘That machine will be your new boss’, a manager tells Marcos, ‘Together you can perform interesting work’. (In the scene in which Marcos is given this new job, the manager convinces Marcos to agree by speaking in cliches, telling Marcos that ‘this factory is as much yours as it is ours’, and that ‘We have all raised it’. Meanwhile, Marcos can’t help but stare at the bare legs of the manager’s pretty secretary.) This sense of the changing times – a transition from a more community-oriented existence to the depersonalised lifestyles of the high-modern – is established in the film’s juxtaposition of Marcos’ humble shack and the grandiosity of the nearby high-rise building in which Nestor lives, and also in an early scene in which Marcos visits the café and Rosa serves him soup made in the factory: ‘It tastes like mother used to make’, Rosa quips, the line referencing advertising slogans that attempt to blur the line between mass-produced food and nostalgia for home-cooked meals.

Lumbered with its deeply-lurid, ever-so-slightly-misleading English-language export title (Cannibal Man or The Cannibal Man), in the UK, Eloy de la Iglesia’s film hacked its way onto the official ‘video nasties’ list in 1983 before being released in a BBFC-classified version, with only three seconds of cuts, by Redemption Video approximately a decade later. However, despite a few instances of grue, Cannibal Man is a relatively chaste, though profoundly bleak, psychological study. For those who first encountered the film after the ‘video nasties’ moral panic (this writer – who first saw the film via the aforementioned Redemption VHS release – included), expectations were most likely torn asunder – much like the cleaver that Marcos uses to bisect the face of Mr Ambrosio, Carmen’s father. (This is the image that graced some of the film’s artwork, including the cover of Severin Films’ Blu-ray release.)

The film is much better served by its original Spanish title, La semana del asesino (‘The Week of the Killer’), which offers a far more accurate attempt to capture the plot than Cannibal Man. Certainly, the film’s protagonist does not participate in cannibalism, other than to feed the hacked-apart bodies of his victims into the new, computerised meat mincing machine at the food factory where he works. (In one scene, Marcos becomes nauseous when he visits the café and Rosa presents him with soup made in the factor in which he works.)

Video

Severin Films’ release of Cannibal Man includes two versions of the film on a region-free Blu-ray disc: an extended cut (107:19 mins) with the title La semana del asesino, which is the main presentation, and the English-dubbed export cut (98:25 mins) titled Cannibal Man. It’s worth mentioning that the extended cut is not the version that originally played in Spanish cinemas: where the censored Spanish cut (not included on this disc) trimmed some of the violence and sexuality – abbreviating the sex scenes between Paula and Marcos, and Rosa and Marcos, and gutting the sequence in which Marcos and Nestor visit the swimming pool at night – the Cannibal Man export cut truncated the scenes set in the factory (whilst also placing one of the grisly slaughterhouse scenes in front of the opening credits). The extended cut contains all of this footage, essentially compositing together both the Spanish version and the export cut.

The extended cut is comparable to the ‘integral’ version of the film that was released on Blu-ray in Spain by Divisa. (A previous Blu-ray release from Subkultur in Germany contained the export cut, with the scenes exclusive to the domestic Spanish cut presented in the disc’s extra features as ‘deleted scenes’.) This ‘integral’ cut of the film incorporates all of the usable footage from the various versions of the picture that have been released. As a result, if the Spanish language audio track is selected, some of the footage originally excised from the domestic cut of the film is presented with English dialogue.

Both versions of the film are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec. The extended cut takes up slightly under 27Gb of space on the dual-layered disc, and the export cut takes up 16Gb. Both cuts of the film are presented in the intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The presentation is excellent, and appears to be taken from the original negative. Contrast levels are superb, particularly in the night-time scenes. There’s a pleasing sense of gradation in the curve to the toe, where deep, inky blacks reside. This results in a very strong sense of depth to the scene set at night. Highlights are even and balanced. A superb level of detail is present throughout, the image being richly textured. Colours are consistent and deep. Damage is limited to a few white blobs and scratches, indicative of wear and tear on the emulsions of the film negative. There is some very slight gate weave evident in one or two scenes too. The encode is pleasing too, ensuring that the natural grain structure of the film is retained. The result is a very, very pleasing, filmlike viewing experience.

Both cuts are presented with the option of viewing the film with its Spanish language audio (as a DTS-HD MA 2.0 dual mono track) or the English dub prepared for the export version (also as a DTS-HD MA dual mono 2.0 track). (The English dub for this film, which will be familiar to those who first saw Cannibal Man via its pre-cert VHS release or the Redemption Video rerelease from the 1990s, is very good.) As noted above, as the extended cut is essentially a composite of the domestic Spanish version and the English-dubbed export cut, both of its audio tracks flit between Spanish and English at times – for scenes that were never dubbed into English or Spanish. Optional English SDH subtitles which transcribe the English dub, and separate optional English subtitles translating the Spanish dialogue, are available. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extra features

In terms of extra features, the disc includes two interviews and promotional material for the film.

In ‘Cinema at the Margins’ (26:11), Stephen Thrower and Shelagh Rowan-Legg (the author of The Spanish Fantastic) are interviewed separately about de la Iglesia’s work. Rowan-Legg situates de la Iglesia’s films within the censorious climate of Spanish cinema. She suggests that Spanish filmmakers found various ways to circumvent the wrath of the censor, including casting non-Spanish actors in order to make the films appear to be more ‘foreign’.

Thrower argues that de la Iglesia was at heart a ‘politically-minded’ filmmaker. He compares de la Iglesia with Jess Franco (who incidentally wrote some music for one of Iglesia’s films Cuadrilátero, 1970), who chose to work outside Spain rather than battle the Spanish censors. Thrower discusses de la Iglesia’s early career, working in television, and his first film: the children’s picture Fantasy 3 (1966), and the progression of his career into the realm of the thriller.

Discussing Cannibal Man, Thrower refers to it as a ‘strange film’, with an emphasis on social inequality. The film has ‘the texture of real life to it’ but the plotting has a sense of ‘sustained implausibility in the way that the crimes unfold’: thus a sense of naturalism is placed in counterpoint with the surreal. Thrower argues that the protagonist is strikingly passive, a trait that Thrower suggests evolved from the original script in which the lead character was to be an 18 year old youth. This changed when Vicente Parra was cast in the role, though the character’s passivity remained.

Rowan-Legg talks about the manner in which de la Iglesia embeds homosexuality in the narrative through the character of Nestor, suggesting that Nestor’s homosexuality within the film is unchallenged because the character comes from a privileged background – another way in which de la Iglesia criticised the hypocrisies of society.

Thrower discusses the film’s release history in the US, where it played on a double-bill with Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil. Initially released in the US as The Cannibal Man, the film was eventually retitled for US audiences as The Apartment on the 13th Floor. He reflects on the film’s association in the UK with the ‘video nasty’ moral panic, arguing that the film’s place on the list of ‘video nasties’ was simply owing to the use of the word ‘cannibal’ in its title.

Thrower talks about the ‘two distinct periods in de la Iglesia’s career’: prior to 1975, the director was making genre pictures with political subtexts, but after the mid-70s and the death of Franco with the resultant liberalisation of social mores and film censorship, de la Iglesia began making films that were more explicitly political and often dealt with homosexuality and disenfranchised social groups. After making El pico (The Needle, 1983) and its sequel, about drug addiction and delinquency, de la Iglesia became a heroin addict himself; this led to a slump in his career.

Thrower compares de la Iglesia with both Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Pier Paolo Pasolini, in the sense that like those filmmakers, de la Iglesia was gay, with a similar interest in ‘rough boys from the underclass’ to Pasolini, and was a Marxist fascinated with the intersection of social class and sexuality.

In ‘The Director and the Cannibal Man’ (17:54), Carlos Aguilar (the co-author of a Spanish book about de la Iglesia) talks about de la Iglesia’s career. The interview is in Spanish, with optional English subtitles. Aguilar says that de la Iglesia was from the Basque region of Spain, and after studying film at university made an impact with his first picture, the family film Fantasy 3. During the 1960s, family films were sustained by significant government grants, so there were a number of Spanish filmmakers who broke into directing by making a family-oriented picture.

With Cannibal Man, de la Iglesia set out to make ‘the most shocking film ever in Spanish cinema’, embedding ‘political and social criticism’ into the narrative. For the first three weeks of production, the filmmakers did not have the correct permit; when the filmmakers approached the authorities for the permit, their request was rejected owing to the subject matter of the film. Production was suspended, and the script was hastily rewritten in order to make it palatable to the censors.

Originally, both Marcos and Nestor were to be 18 or 19 years old, and the homosexual relationship between the two was more explicit. However, this wasn’t permitted: the suggestion of homosexuality between two male characters was only allowed if the characters were ‘mature, but not if they were teenagers’. Hence, de la Iglesia changed the ages of the characters. The censors also objected to the original ending of the picture, which was more open-ended; the filmmakers remedied this by writing an ending in which Marcos turns himself in to the police. However, even despite the rewrites, the completed film offended the Spanish censors so much that they demanded those 62 cuts.

Parra, playing ‘an insane and possibly gay proletariat’, was playing against type: the actor was more frequently associated with aristocratic roles in films. However, Parra’s performance in Cannibal Man won awards for the actor, proving to critics and audiences that he was capable of playing a broad range of character types.

The next year, in 1973, de la Iglesia and Parra would go on to collaborate on No One Heard the Scream (Nadie oyó gritar). This film also featured Carmen Sevilla, who de la Iglesia had directed in The Glass Ceiling (El techo de cristal, 1971), in a role that, like Parra’s performance in Cannibal Man, challenged the types of wholesome, innocent characters with which Sevilla had been associated previously.

Aguilar argues that Cannibal Man is not a serial killer picture or a slasher film: its protagonist, Marcos, ‘is a proletariat, not too smart, an uneducated man who has a sad life’. He kills by mistake, and then murders other people in order to cover up his original crime. The characters he kills ‘represent all the repression he has’: ‘Sexual repression, familial repression, social repression, financial repression, and even political repression’.

Aguilar talks about the importance of the set decoration, by Santiago Ontañón, to Cannibal Man, in terms of the naturalistic aesthetic of the film. This was enhanced by the photography, by Raul Artigot.

The film took two years to reach cinemas in Spain, and on its initial release it didn’t perform particularly well at the Spanish box office. However, over time it has acquired a cult reputation, ‘in a false way’, through the perception of it as a ‘sleazy, violent, nasty film’, but in fact, Aguilar says, the violence in the picture ‘has a meaning rather than just being a cheap spectacle’.

The film’s English-language trailer (3:07) is also included, as is a montage of deleted footage (1:35). Some of this material is silent and monochrome, depicting the arrest of Marcos and his journey in a police car; also included is a longer, also silent, shot of Marcos and Rosa engaged in coitus; and a brief scene in which Marcos and Nestor kiss passionately (again, this is silent).

An impactful film ostensibly about the escalation of violence, Cannibal Man seems to contain some deliberate references to Hitchcock’s thrillers but in tone feels much more in line with the paradigms of film noir, with Marcos as a proletarian man who finds himself enmeshed in a downward spiral caused by a momentary loss of self-control. The passage of the week is displayed by the use of onscreen titles denoting the day on which the events take place. With each day comes the death of another victim of Marcos. The overall effect is of a relentless tirade of violence which carries its own seemingly unstoppable momentum. Worked into this is a deconstruction of Latin machismo, and a negotiation of the mercurial boundaries of human sexuality. This was the first of de la Iglesia’s film to explore male homosexuality, which would become an overriding characteristic of the director’s later films – after the liberalisation of Spanish cinema that occurred following the collapse of the Franco regime.

What is easy to overlook, or forget in the space between viewings, is the film’s deep vein of black comedy. ‘Don’t worry, people are only killed that easily in movies’, Marcos tells a worried Paula after he has killed the taxi driver by hitting him on the head with a rock. In another scene, a colleague of Marcos’ blathers incessantly, and in graphic detail, about the death of Marcos’ mother, who burned to death in an industrial accident at the factory – after telling Marcos that he will not recount the incident in any detail.

Cannibal Man is a superb film. Severin Films’ Blu-ray release is excellent, containing a glowing presentation of both the ‘integral’ version of the picture and the shorter export cut, alongside some superb contextual material.

[i] Lazarro-Reboll, Antonio, 2012: Spanish Horror Film. Edinburgh University Press: P.138

[ii] Ibid.: P.139