Chiefly circulated amongst fans of extreme cinema in a version culled from its US VHS release, under the tacky title Naked Massacre, the 1976 picture Born for Hell offers an intriguing look at the case of Richard Speck, who during a single night in 1966 murdered eight student nurses in a Chicago townhouse – through the disorientating lens of an international co-production. Filmed in Belfast, Dublin, and West Germany, Born for Hell is credited to the Canadian filmmaker Denis Héroux, and seems an unusual fit in Héroux’s body of work. However, Mathieu Carrière suggests that the film was instead largely the product of the Hungarian director Géza von Radványi. Severin Films have released Born for Hell on Blu-ray in an impressive package, including both the director’s cut and the abbreviated Naked Massacre edit alongside some insightful contextual material.

Belfast, during the Troubles. Cain Adamson (Mathieu Carrière), an American soldier returning from Vietnam, stops off on his way home to the United States. He takes lodgings in a seedy hostel, where he meets a young Vietnamese man. The pair engage in quietly hostile dialogue at first, culminating in the young Vietnamese man propositioning Adamson, testing the American’s sense of surety in his sexuality and sense of self. However, soon they engage in quasi-philosophical dialogue with one another, linked by their shared status as cultural outsiders.

Nearby, a group of student nurses are lodging in a house together. These include Bridget (played by Debra Berger, the daughter of William Berger), Amy (Carole Laure), Jenny (Leonora Fani), Christine (Christine Boisson), Leila (Myriam Boyer), Pam (Ely de Galleani), Catherine (Eva Mattes), and Eileen (Andrée Pelletier). Owing to the violence on the streets, the nurses are advised not to leave the house alone, and are transported to and from the hospital by police van.

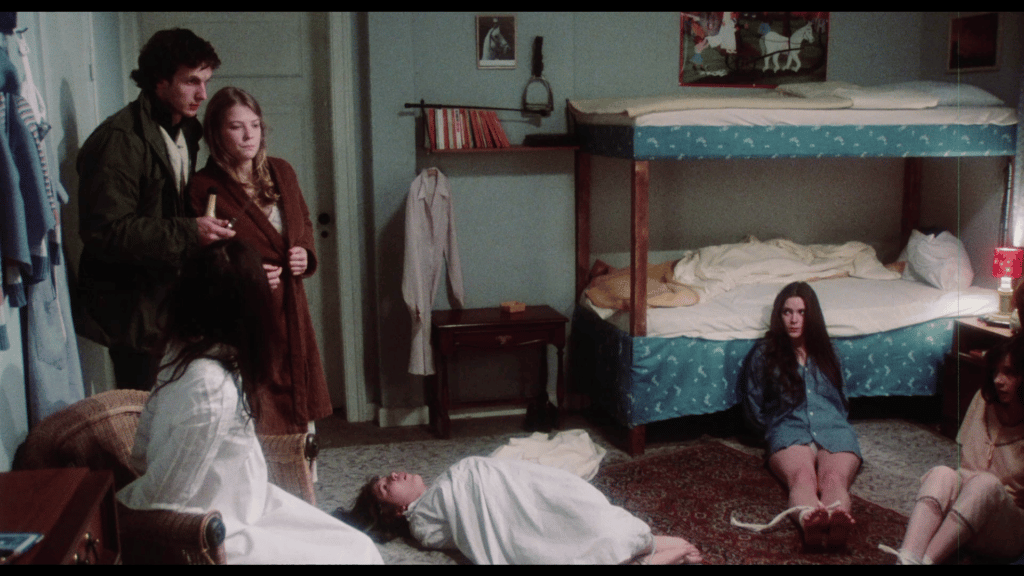

Adamson begins to frequent a pub near to the house in which the nurses are living. He sees in one of them an echo of the wife he left behind in the States. Seemingly motivated by this, one evening Adamson forces his way into the house. He takes the young women hostage, murdering them one-by-one.

There are clear echoes of the Speck case. In July of 1966, oddball loner Richard Speck murdered eight student nurses after breaking into the South Chicago townhouse that functioned as their dormitory. High on drink and drugs, Speck trapped the women in a room before luring them out one-by-one, whereupon he would kill them using a knife or by strangling them. However, he left a ninth woman, who crawled and hid under a bed, alive. This woman, Corazon Amurao, was the nurse who had answered the door when Speck knocked earlier in the evening – leading to Speck forcing his way into the house. (Speck had presumably lost count of the number of women in the house and forgotten about his ninth captive.) Amurao was later able to offer a description of Speck and his distinctive tattoo, which Speck had acquired whilst serving prison time in the early 60s: this tattoo read, simply, ‘Born to Raise Hell’. During the manhunt that ensued, Speck attempted suicide by slashing his wrists in the seedy hotel in which he was living, and was arrested after a doctor treating his wounds recognised the ‘Born to Raise Hell’ tattoo on Speck’s left forearm, which had been highlighted in the press coverage of the murders.

As Joe Coleman, artist and connoisseur of ghoulish Americana, says in the interview on this disc, Speck missed out on being labelled, by any strict definition of the term at least, as a serial killer simply by the fact that the murders he committed took place in the same location and on the same night. However, the Speck case was roughly contemporaneous with a number of other high-profile incidences of violent murder that shifted the paradigms of public perception of serial homicide (to use a term that would not be officially coined until its use by FBI Special Agent Robert Ressler in 1974). These included the crimes of the Boston Strangler, the Zodiac Killer, and the Tate-La Bianca murders – and like those crimes, the Speck case buried its way into the public subconscious, inspiring a number of films, not to mention the strategies used to market them to an audience hot for narratives focusing on serial killers.

For example, Fernando di Leo’s 1971 thrilling all’italiana Slaughter Hotel (La bestia uccide a sangue freddo) was marketed in the US with a lurid one-sheet poster that directly referenced the Speck murders. ‘Carved out of today’s headlines!’, screamed the poster, a black and white mock-up of the front page of a newspaper, ‘See the slashing massacre of 8 innocent nurses!’ Beneath these words was a monochrome photograph of a pile of female corpses, and below this the film’s title: ‘Slaughter Hotel … a place where nothing is forbidden!’ Similarly, Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974) filters the Speck murders through its proto-slasher lens, using a sorority house as the key setting for its narrative – which focuses on a killer who, like Speck, murders the young women inside one-by-one. Clark’s picture formed a template that many later slasher films would emulate: for example, Mark Rosman’s The House on Sorority Row (1982), and Amy Holden Jones’ The Slumber Party Massacre (1982) and its sequels. Thus Speck’s murder spree arguably anchored the core tenets of a specific subtype of the American slasher picture.

The film that most immediately referenced the Speck case was Wakamatsu Kôji’s Violated Angels, released in 1967, only a year after the murders occurred. An exploitative Pinku picture, Violated Angels was shot quickly (over three days) and predominantly in black and white – with some colour footage in the final sequence. It is very much dissimilar to Born for Hell, other than in the respect that both films relocate the Speck murders into very different cultural contexts. Where the narrative of Violated Angels is set in Japan, Born for Hell – the title of which alludes to the phraseology of the tattoo that led to Speck’s arrest – takes place in Belfast during the Troubles.

Though Canadian filmmaker Denis Héroux was credited as the director of Born for Hell, lead actor Mathieu Carrière states in the interview on this disc that the film was mostly directed by the Hungarian director Géza von Radványi, who is credited with the film’s story and as its producer. Radványi’s naturalistic style is certainly evident in Born for Hell, which features a heavy use of cinema-verité-style photography and editing. The director’s cut on this disc, which is the main presentation, enhances this through its avoidance of non-diegetic music and use of genuine newsreel footage of the Troubles (and also the Vietnam War). (Chris O’Neill’s video essay, ‘Bombing Here, Shooting There’, states that this emphasis on realism extended to the spontaneous casting of a British soldier – who had stopped the production team in order to ask to see their identification – in the film.)

Most viewers who have encountered Born for Hell after its original theatrical release, however, will have seen the picture via the cut that was released on VHS in the US, under the more lurid title Naked Massacre, in 1984. That version of the film, which has been available via various bootleg VHS releases and grey market DVDs, is included on this disc as an extra feature. It differs from the director’s cut in its abbreviation of the film’s opening moments, eliminating the onscreen scrawl that attempts to outline the tensions in Northern Ireland, and by its inclusion of non-diegetic music, not to mention the manner in which some of the later scenes are edited.

In the video essay contained on this disc, Chris O’Neill suggests that the decision to set the film in Belfast during the Troubles was almost arbitrary, and the dialogue (post-synched, apparently in Canada, with only Carole Laure and Andrée Pelletier providing their own voices) offers a hodgepodge of accents and stereotypes – mostly erroneously associated with the Republic of Ireland rather than Northern Ireland. (The exteriors for the film were shot on location in both Belfast and Dublin, with the interiors lensed in West Germany.)

However, via Adamson’s status as a veteran of the war in Vietnam, it seems that Born for Hell seems quite intentionally to draw parallels between Belfast at the time of the Troubles and Vietnam during the years of American-led fighting against the NVA. Both are sites of colonial violence, in which attempts are made via guerrilla tactics to displace what is regarded as a colonising force. Via both newsreel footage and scenes staged for the film, we see British troops on the streets, asking citizens for their identification papers, and engaged in running combat with paramilitary groups. Heightening the parallels that the film draws between Northern Ireland and Vietnam, we also see similar newsreel footage of the war in Vietnam, via a television set that the nurses watch. (‘Same old news: a bombing here, a shooting there’, one of the young women observes.)

When Adamson first arrives in Belfast, he seeks shelter in a church. However, a bomb explodes, and there is screaming. Endless screaming and smoke. Adamson carries one of the wounded out of the church, where he is told by a British soldier that an ambulance is outside. ‘He’s dead’, Adamson responds curtly, the moment underscoring the protagonist’s casual, matter-of-fact relationship with violence and death. Outside, billboards display government-mandated warnings not to allow children to play with guns, whilst groups of youths are shown mimicking the violence of the adult world. Adamson encounters such a group of children: one boy holds a blindfold, whilst another holds a toy submachine gun. The imagery recalls some of the most iconic images of the Troubles: the documentary photographer Homer Sykes, for example, captured a number of famous photographs of children playing with toy assault rifles amidst British military vehicles. (This is the kind of imagery that, almost 20 years later, would also work its way into the music video for The Cranberries’ ‘Zombie’.) However, Born for Hell’s depiction of childhood’s association with violence is also reminiscent of the work of Sam Peckinpah: viewers may recall the battle of Starbuck in The Wild Bunch (1969), Peckinpah’s own veiled critique of American involvement in Vietnam, and its aftermath, in which a group of children mimic the nihilistic violence they have just witnessed.

In the aforementioned video essay, Chris O’Neill also states that Born for Hell plays into the reductive perception that the Troubles were purely sourced in religious difference and persecution ‘rather than a complex web of deep-rooted political tensions’. At one point, as part of the local ‘colour’ worked into the picture, Adamson visits a pub in which the denizens discuss the Troubles. ‘You know, this is going to be the last of the religious wars’, a man says, to which his friend responds: ‘And this bloody war’s been going on for 400 years’. ‘And I don’t even remember if my parents were Protestant or Catholic’, a woman adds, underscoring the senselessness of the violence that is shown being enacted on the streets of the city.

Against this overt layer of political violence is an undercurrent of gender-based aggression: one plays off against the other, culminating in Adamson’s brutal assault upon the nurses – which carries the violence from the city streets into the relative sanctity of the house in which the women are staying. (A loose equivalence is thus drawn between political violence and Adamson’s misogynistic fury, compounded by a policeman’s onscreen exclamation after the murders have been discovered: ‘Must have been a terrorist’, he tells his colleague.) Mid-way through the film, one of the men in the pub refers to the nurses as ‘The last virgins in Belfast’, to which the young Vietnamese man, whom Adamson meets in the hostel, adds: ‘They’re all hookers. The more innocent they look, the more they cost’. When, later, the young Vietnamese man suggests that Adamson is ‘scared of women’, in a subsequent scene Adamson is shown chasing away two men who are attempting to rob a middle-aged prostitute (who looks far from innocent). The woman, Molly, takes Adamson home for a ‘free one’ in compensation for his intervention in the attempted robbery. She strips naked, covering a statue of Christ in a darkly comic expression of modesty, but Adamson is having none of it: he rejects her blunt attempts to get him to fuck her. He departs, but before he does so, she asks him if he ‘doesn’t like women’. ‘Goddamn pansy!’, she spits in anger as he walks out the door.

Clearly (and deeply stereotypically) gay, the young Vietnamese man functions as a foil to Adamson, his presence a suggestion of complexity, or hidden ambiguity, within Adamson’s apparent heterosexuality – hinting at Adamson’s motive for killing the nurses. ‘I’d do you for peanuts’, the young Vietnamese man tells Adamson camply, ‘I’m not greedy’. It is unclear whether this character is intended to be real or imaginary – a product of Adamson’s experiences in Vietnam fused with his sexual insecurity. Certainly, the character’s presence in the diegesis enables Adamson to reflect on his past. (Though this young Vietnamese man does not participate in the murders of the nurses, the effect is not dissimilar to the pairing of Michael Rooker’s aloof Henry Lee Lucas and Tom Towles’ randy Ottis Toolle in John McNaughton’s later Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, 1986.) Adamson tells this character about his sister, who after a period of time as a teenage prostitute, killed herself at the age of 18; in response to this revelation, the young Vietnamese man goads Adamson by suggesting the latter was engaged in an incestuous relationship with his sister: ‘Did you make it with her?’, he asks, before adding: ‘You’re not psycho, by any chance? Women do that to a man’.

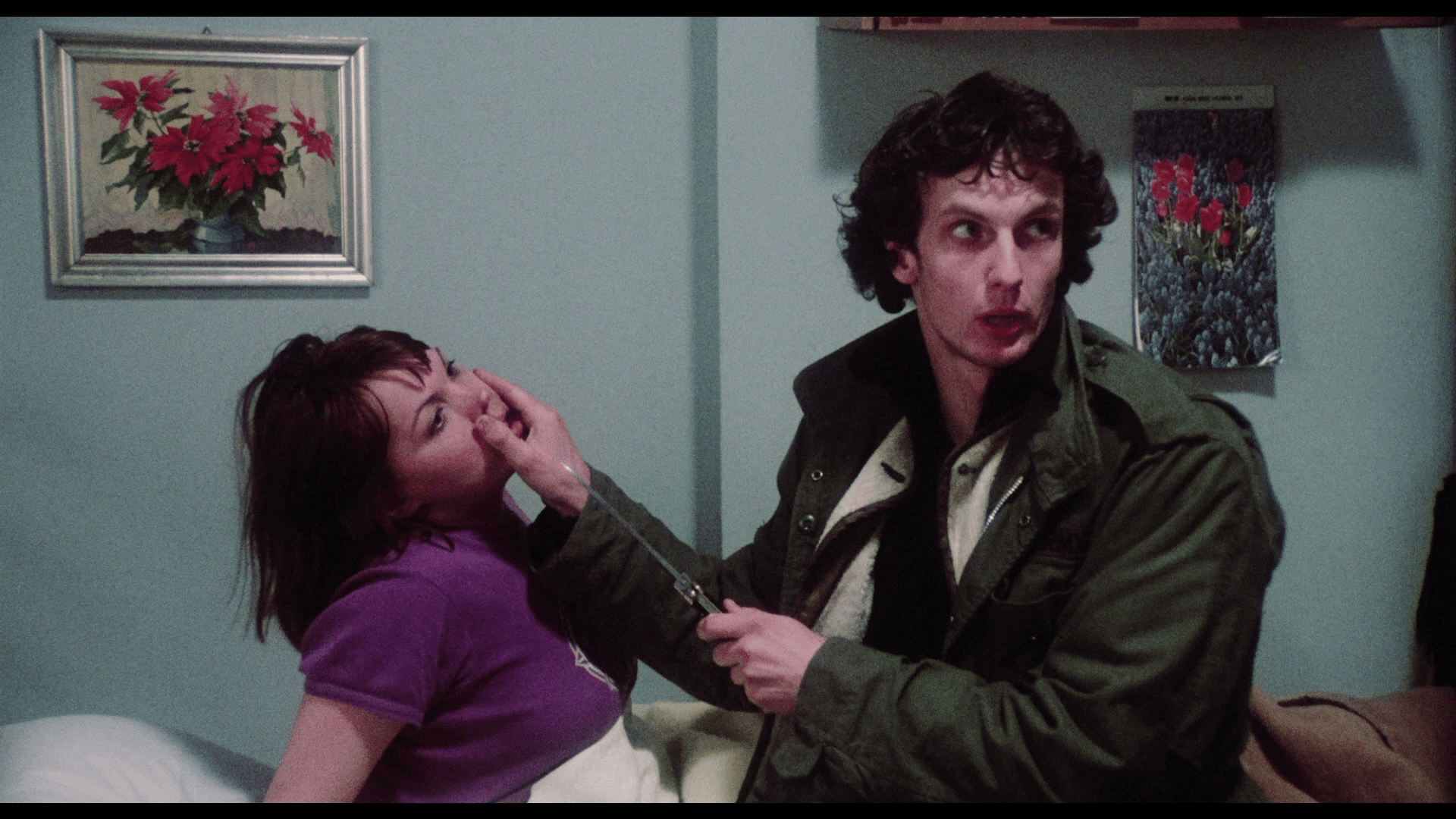

In Violated Angels, the aforementioned film by Wakamatsu that is based on the Speck murders, the lesbian sexuality of two of the victims is foregrounded for exploitative effect. The same is true of Born for Hell, in which one of the nurses, Christine, is shown almost desperately attempting to seduce her contemporary, Jenny, who appears utterly naïve towards Christine’s very obvious desire for her. When Adamson sneaks into the nurses’ house, he threatens Christine and Jenny first, holding them at knifepoint and demanding money ‘to go home to the States’. Later, as if taking a page from the playbook of David Hess’ Krug Stillo (in Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left, 1972), Adamson forces Christine and Jenny to engage in coitus whilst he watches, before making one of them stab the other. (One can almost imagine Junior Stillo on the sidelines, excitedly jibbering: ‘Make them make it with each other, man!’)

Throughout the film, there is the suggestion of the psychological cost of experiences in combat, enabling Born for Hell to sit alongside other pictures about combat fatigue amongst veterans of the war in Vietnam – from the likes of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), to Ted Kotcheff’s First Blood (1982) and Buddy Giovinazzo’s Combat Shock (1986). However, despite a clear sense that the protagonist is haunted by his experiences in combat, behind the violence Adamson commits against the nurses are unknowable motives. The film hints at sexual insecurity, and it also suggests traumatic events in Adamson’s youth (for example, his sister’s suicide); but on the other hand, Adamson’s accounts of his experience are not necessarily reliable. ‘Maybe he hates us all’, one of the nurses suggests, ‘Maybe he wants revenge [….] Some men detest women. Frustration. Something in his childhood’.

It is perhaps intentional that the nurses are barely distinguishable from one another, other than the extent to which they conform to various ‘types’: the pregnant one, the naïve one, the gay one, and so on. They are little more than blank cyphers, targets for the violence that erupts within Adamson. Their faces appear in close-up monochrome still photographs at the close of the film, the impassivity of each one’s gaze compounding the seeming inevitability of their murders.

Specification

Coded for playback in region ‘A’ machines, Severin Films’ Blu-ray release of Born for Hell contains two cuts of the film: the director’s cut (running 91:37 mins and filling approximately 22Gb of space on the dual-layered Blu-ray disc), and the shorter Naked Massacre edit (running 85:43 mins and filling approximately 16Gb of space) that has been in wider circulation since the film’s 1984 videocassette release in the states.

Both versions of the film are presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

The 35mm colour photography is captured very nicely on this Blu-ray release. There is a pleasing level of detail throughout both presentations of the film. Contrast levels are good, with deep blacks. The presentation is sourced from a new 2k scan of a 35mm print; the use of a print, rather than the (presumably lost) negative, is evident in the sharp drop into the toe, which results in some shadow detail being ‘crushed’, and the slightly ‘hot’ highlights. Colours are consistent throughout, the cinematography emphasising the drab hues of the brickwork and streets of the exterior sequences. In some scenes, there seems to be a slight push towards a sickly green hue, which may or may not be intentional. Natural film grain is present though this is sometimes mitigated by the encode to disc – with the grain structure sometimes looking very slightly awkward in motion. There is some organic film damage to the source, with some noticeable (but not distracting) marks in the emulsions and vertical scratches here and there and, it seems, a few missing frames in a couple of instances. On the whole, it’s a pleasingly filmlike presentation

In terms of audio options, the director’s cut includes the option of both English and French dialogue tracks. (Both tracks are DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0.) Optional English subtitles are included; these are based on the English-language track. On the other hand, the Naked Massacre cut includes an English DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 track only, also with optional English subtitles.

Both English and French audio options are fine, the English track offering a richer soundscape with a stronger sense of range.

Extras

Alongside the two cuts of the main feature, the disc includes some superb contextual material.

‘The Other Side of the Mirror’ (14:14 mins) is an interview with principal actor Mathieu Carrière. Carrière talks about his career as an actor. The interview is illustrated with clips from Harry Kumel’s Malpertuis (1971), and some of the other films in which Carrière also acted. (Carrière also talks about working on Peter Patzak’s 1975 film Parapsycho, and Werner Schroeter’s 1991 picture Malina.) Carrière reflects on working with Orson Welles for Malpertuis, revealing that Welles refused to remove his cigar for takes and struggled to learn his lines. Carrière says that if he ‘continued in this silly business’, he wanted ‘one day to get as much money as Orson Welles’.

Discussing Born for Hell, Carrière says that the film had to change the name of the killer, the number of victims, and the location – in order to distance the production from the crimes of Richard Speck. Carrière says that his mother had ‘second thoughts’ when he was offered the role in Born for Hell but he was convinced to play the part by Carrière’s father, a psychiatrist. Carrière suggests that what he liked about the finished film was that ‘it made no attempt at being psychological. It had a kind of “flatness” about the facts, the horrible facts, which I liked’. Géza von Radványi, who is credited with the original story and as supervisor but really operated as a de facto director, was asked by Carrière why his character murders the women in the story, and Radvanyi told Carrière that he believed the character was ‘writing his autobiography, unconsciously’; this gave Carrière a ‘good key’ for his performance in the film.

‘Nightmare in Chicago’ (12:52 mins) is a featurette focusing on the Richard Speck murders, featuring interviews with filmmakers John McNaughton (Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer) and Gary Sherman (Dead and Buried), both of whom are from Chicago.

Both interviewees offer their memories of the Speck murders. They connect this to the Peterson-Schuessler murders that took place in Chicago in 1955, in which three young boys were killed and their bodies dumped in Robinson Woods; this crime wasn’t solved until the mid-1990s. ‘Chicago was a tough town’, McNaughton says, though the Speck murders hit close to him because of their geographical closeness to where he was living at the time. ‘It was a bad time’, Sherman offers, ‘and it only got worse’ with the violence surrounding the Democratic National Convention protests in 1968 – which led to Sherman leaving the country and settling in London.

‘A New Kind of Crime’ (38:20 mins) features podcaster Esther Ludlow (from the Once Upon a Crime podcast) reflecting on the Speck case. Ludlow’s commentary on Speck’s life and crimes is detailed and lively. She describes the circumstances of the Speck murders and discusses Speck’s background, suggesting that Speck’s character was formed largely by his relationship with his cruel, alcoholic stepfather, whom his mother married following the death of Speck’s father, and his experiences at school – which led to a tendency towards petty crime. His defiant attitude escalated throughout his youth. In 1962, he married his wife, and whilst in prison (where his ‘Born to Raise Hell’ tattoo was created), his daughter was born. After his release from prison, Speck was cruel to his family, including enacting violence against his daughter; his violence escalated through a number of incidents, culminating in the murders of the nurses in 1967.

‘Bombing Here, Shooting There’ (17:02 mins) is a video essay by Irish filmmaker and critic Chris O’Neill. O’Neill talks about Born for Hell in the context of Irish film history. He says that the exterior scenes were shot in both Belfast and Dublin (interiors were filmed in West Germany), highlighting the fact that the film ‘is the only extreme cinema production to be associated with either Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland’.

During filming in Belfast with Mathieu Carrière, the filmmakers were stopped by British soldiers and asked to show their identification. O’Neill says that an opportunity was seized, and one of the British soldiers was asked to perform the same action on camera: this is the soldier who is shown asking for Adamson’s identification near the beginning of the picture.

O’Neill suggests that Adamson’s background as a veteran of the war in Vietnam helps contribute to ‘an atmosphere of brutality and pessimism’. The ‘distinctly strange atmosphere’ of the film is emphasised by the post-synch dubbing and the ‘lack of natural acoustics that would have been present on the set’. The film’s dialogue, O’Neill argues, uses ‘cringey and amusing’ Irish stereotypes that are ‘closer to the caricatures commonly associated with the Republic of Ireland than to Northern Ireland’. The film’s depiction of the Troubles, O’Neill suggests, plays into the reductive, but popular, perception that the conflict was simply driven by religious persecution ‘rather than a complex web of deep-rooted political tensions’.

However, the film’s moments of absurdity don’t negate its nihilistic tone, O’Neill argues: he suggests that Born for Hell is ‘a different kind of film’ to the other exploitation films of the era filmed in Ireland (such as Riccardo Freda’s 1971 giallo all’italiana The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire / L’iguana dalla lingua di fuoco). Instead, the film bears comparison with ‘home invasion’ thrillers of the period, such as Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1972) and Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left (1972). However, unlike those films, there is no ‘payoff’ to the violence depicted in Born for Hell.

O’Neill also suggests that Born for Hell was so poorly distributed perhaps because of the censorship issues that some of its peers had faced; certainly, he argues it was because of this that Born for Hell was never purchased for distribution in Britain or Ireland.

‘Artist Joe Coleman on Richard Speck’ (14:21 mins) sees Coleman discussing Speck’s murder spree. Coleman talks about Speck’s life, and reflects on the impact of Speck’s crimes on Coleman’s own fascination with serial killer culture – which as Coleman says, evolved alongside the era of (fictional) monster culture. Coleman compares Speck’s crimes to the My Lai massacre and other similar incidents of the war in Vietnam, including the incident at Kent State and the scale of ‘human suffering’ instigated by Richard Nixon’s presidency. Where Speck was caught and punished after his suicide attempt, ‘Richard Nixon never felt that he did anything wrong’. Coleman also talks about his admiration for Born for Hell and the manner in which it adapts the facts of the Speck case.

‘Inside the Odditorium with Joe Coleman’ (9:41 mins) features Coleman discussing some of the items within the Odditorium, his private museum. These include a painting by Speck of a bird, which the murderer painted whilst in prison; Speck’s ‘cameo’ in Coleman’s autobiographical paintings ‘Faith’ and ‘Coal Man’; the wax figure of Speck that Coleman keeps in his Odditorium; and others.

Also included is a trailer for the film’s theatrical release in Italy (2:58 mins), where it was titled ‘E la notte si tinse di sangue’ (‘And the Night was Tainted with Blood’).

One of the most extreme films made in either Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland, Born for Hell is a fascinating film. There is a deliberate lack of suspense, owing to the ‘“flatness” about the facts’ Carrière talks about in his interview: the endpoint of the narrative (the deaths of the nurses, and of Adamson himself) seems utterly, irrevocably, inevitable. The misogynistic fury of the film’s protagonist, the Speck-inspired Cain Adamson, is offset by the political violence of the film’s setting. One is a dark mirror of the other. The film also draws parallels between the Troubles and American involvement in Vietnam. Played by Matthieu Carrière with a similar sense of lethargy to the ‘sleepwalkers’ of Paul Schrader’s films (for example, Taxi Driver, Hardcore, Light Sleeper), Adamson is the character that links these various manifestations of desire, bloodshed, and territorialism.

Though as Chris O’Neill suggests in his video essay, Born for Hell trades on stereotypes (predominantly those associated with the Republic of Ireland, rather than Belfast), given the strange, otherworldly atmosphere of the film – enhanced by the post-synched dialogue – this doesn’t seem to detract from the whole enterprise, instead contributing to the strange spell that Born for Hell weaves. The adjective ‘nihilistic’ is often used with casual abandon in reference to examples of horror and exploitation cinema, but seems deeply appropriate in the case of Born for Hell: the film’s narrative depicts a world in which enmity and violence (either without apparent motivation, or with motivations that have been lost to the mists of time) is an inevitable – nay, essential – part of life. The rephrasing of Speck’s tattoo (‘Born to Raise Hell’) as ‘Born for Hell’ is arguably meaningful here: where the former phrase may be interpreted as suggesting hedonism, the latter phrase has more nihilistic connotations. The blank realism of the film, guided (Carrière says) by the characteristic naturalism of Radványi, results in a picture that refuses to pass judgement on its protagonist’s actions, hinting at the psychopathological motives that lead to such outbursts of violence without offering any reassuringly reductive ‘solutions’.

Long difficult to see in a decent version, and with the Naked Massacre cut seemingly the only version of the film in circulation on home video, Born for Hell has thankfully received an excellent release from Severin Films. The inclusion of both the director’s cut and the Naked Massacre edit is very welcome, and the film is supported with some excellent contextual material.

Born For Hell is available via Severin Films: for more information on this release, please click here.