The production of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in the Pagsanjan region of the Philippines left behind a local filmmaking infrastructure ripe for exploitation. During the 1980s, numerous filmmakers capitalised on this. Severin Films have released one such film, Alan Birkinshaw’s 1982 picture Invaders of the Lost Gold, on Blu-ray for the first time.

Made in the Philippines for Dick Randall, that most notorious distributor and producer of no-budget exploitation films, Invaders of the Lost Gold – or Horror Safari, or Greed (the onscreen title of the print on this disc) – was directed by New Zealand-born Alan Birkinshaw. This was Birkinshaw’s third feature film: his career as a director is nothing if not diverse. Birkinshaw’s debut feature, after a number of years working in television, had been the 1974 sex comedy Confessions of a Sex Maniac (later retitled The Man Who Couldn’t Get Enough, to avoid confusion with the ‘Confessions’ series of films). His second film was Killer’s Moon (1978), which he also wrote; but before entering production on Killer’s Moon, Birkinshaw sought (uncredited) assistance from his half-sister, the novelist Fay Weldon, who helped to hone the film’s dialogue.

Invaders of the Lost Gold was scripted by a man named Bill James, who lived in the Philippines and functioned as a ‘fixer’ during the film’s production. James’ script was based on the rumours of gold left behind in the Philippines after the Japanese Imperial Army surrendered at the end of the Second World War. This gold, looted by Japanese troops from various sites, was claimed to be stashed in around 150 locations – caverns and caves – by General Tomoyuki Yamashita. There have been various suggestions over the years that treasure hunters have found parts of this illicit stash, though the general consensus remains that the gold doesn’t exist and the stories are simply an extension, and modernisation, of fables that have circulated in the Philippines since the 17th Century – and the rumours that Limahong, the Chinese pirate, buried his treasure somewhere near Pangasinan.

Invaders of the Lost Gold opens in 1945, with a column of Japanese soldiers led by Colonel Yakuchi. The column is carrying a number of wooden boxes containing gold bullion. Attacked by tribespeople, the Japanese troops retreat to a cave and conceal the gold. Yakuchi, and his officers (Toyota and Tobachi) make a vow to only return to the cave together.

36 years later, in Tokyo, writer Rex Larson (Edmund Purdom) approaches Yakuchi (Protacio Dee), now masquerading as a businessman under the name of Sugiyama, and demands to know the whereabouts of the 10 cases of gold. Violence erupts, and Larson shoots and kills Yakuchi and his bodyguards, before visiting Toyota and asking the same questions. Toyota’s response is to retreat to a back room and commit seppuku. Finally, Larson approaches Tobachi (Harold Sakata), who is now running a school of martial arts. Tobachi agrees to accompany Larson on an expedition to the Philippines, for 25% of the value of the gold.

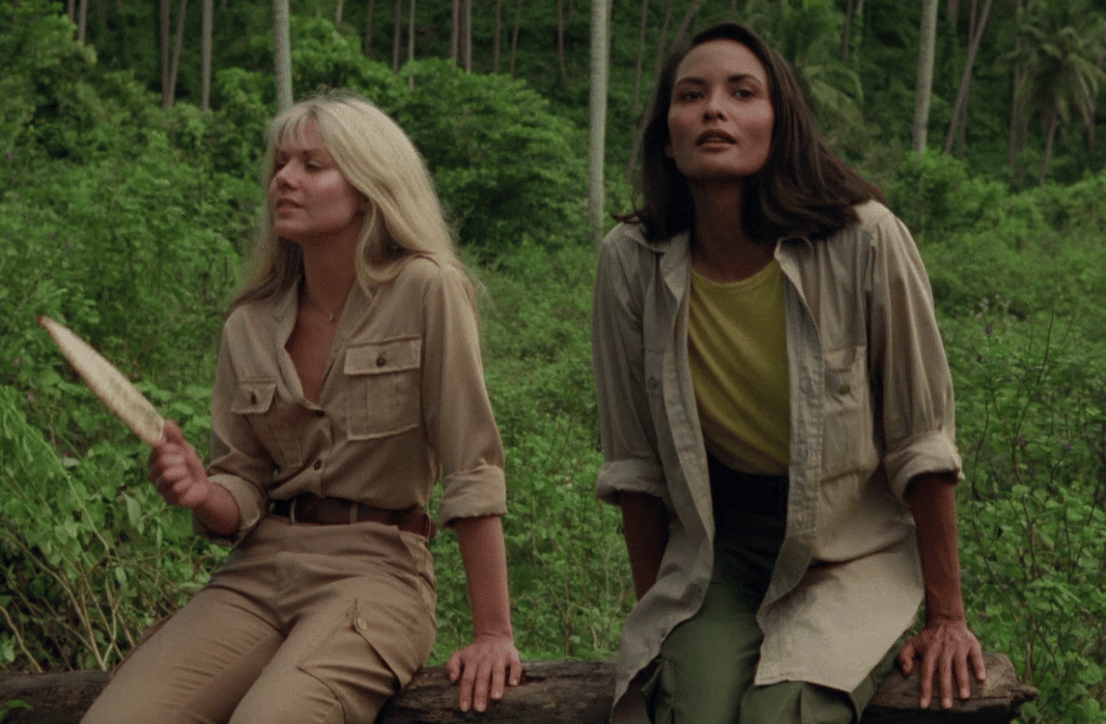

Larson asks the wealthy Jefferson (David De Martyn) to bankroll the expedition. Jefferson has the connections required to smuggle the gold out of the Philippines and sell it on the black market. Jefferson agrees, but only if Larson will concede to allowing Mark Forrest (Stuart Whitman), with whom Larson has bad blood, to lead the expedition. Jefferson also takes Cal (Woody Strode), one of his bodyguards, on the expedition. Meanwhile, Jefferson’s pretty daughter (Glynis Barber) demands to accompany her father, despite his wishes, and uses her charms to lure Forrest into agreeing to lead the expedition. During the expedition, Janice begins to fall for Forrest. But danger lurks in the jungle, and the key members of the expedition are picked off one by one.

Exploitation films have often coasted along through clever casting decisions. Like many of its brethren, Invaders of the Lost Gold’s major draw, arguably, is the manner in which it gathers together various stars who were seen as past their commercial prime: Edmund Purdom, whose career as MGM’s next star was halted following his affair with Linda Christian, the wife of Tyrone Power, leading to work in television and various film productions in Europe; Stuart Whitman, whose Hollywood leading man roles had eventually segued during the 1970s into television work, and features with directors such as Rene Cardona, Jr, and Tobe Hooper; Woody Strode, who following his role in Sergio Leone’s Italo-Western Once Upon a Time in the West had appeared extensively in Spaghetti Westerns, Italian poliziesco pictures, and other exploitation genres; and Harold Sakata, whose career had been haunted by his performance as ‘Oddjob’ in Guy Hamilton’s Goldfinger (1964), and who would give his final screen performance in Invaders of the Lost Gold.

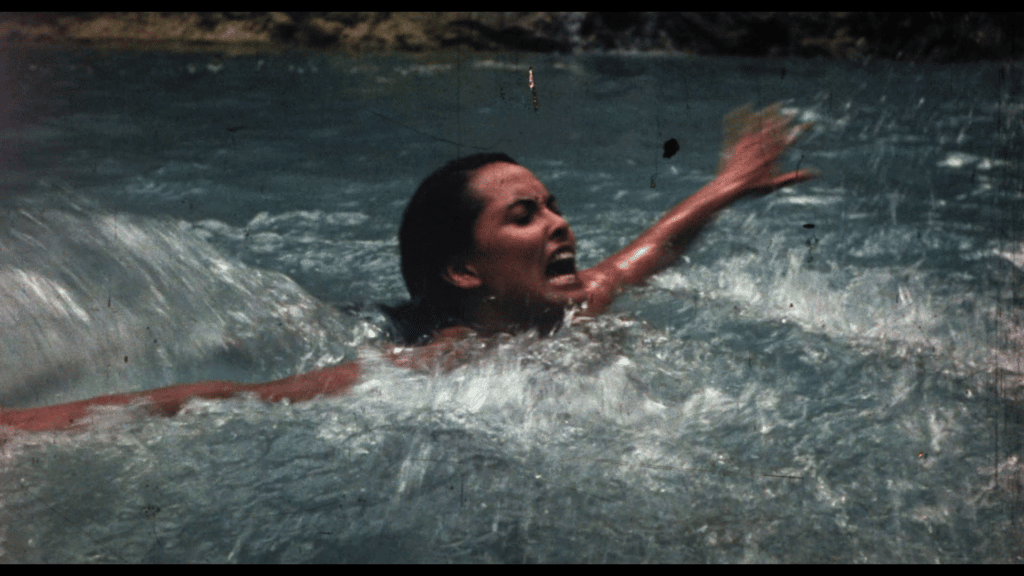

Into this mix, Invaders of the Lost Gold adds ‘Black Emanuelle’ herself, Laura Gemser, as Forrest’s former love interest, Maria, who joins the expedition to accompany her current beau, the expedition’s guide, Fernando (Junix Inocian). Gemser’s role in the film seems essentially to provide Invaders of the Lost Gold with its exploitative linchpin: a sequence in which Gemser takes time out from the expedition to go skinny-dipping in a small natural lake, the camera caressing her nude form, before… something happens, and Maria drowns. This something is indescribable, because all the audience is presented with is extreme slow-motion footage of Maria thrashing about in the water.

This elliptical presentation of Maria’s death is characteristic of the film’s scenes of violence. As the expedition travels (oh-so-slowly) along the jungle river, making various stop-offs for overnight camps along the way, a number of disasters befall its members. A porter is attacked and killed by a crocodile; Fernando is bitten by a venomous snake. The death of the porter is depicted in a similar manner to the demise of Maria: extreme slow-motion, rendered almost incomprehensible through the use of very tight close-ups of the action, with no master shot to anchor them.

In the interview with Birkinshaw on this disc, the director states that he found Bill James’ script to be lacking: Birkinshaw would redraft scenes on the evening before they were to be shot, ‘and give the actors their scripts in the morning at the breakfast table’. This ad hoc approach to the script is evident throughout the production, with scenes feeling dictated by a degree of randomness and disconnection, and a curious lack of thrust in the storytelling. Coverage is most often minimal; and to describe the film’s dialogue as frequently ‘clunky’ would be an understatement, with many narrative loose ends that are less tantalisingly ambiguous and more frustratingly underdeveloped.

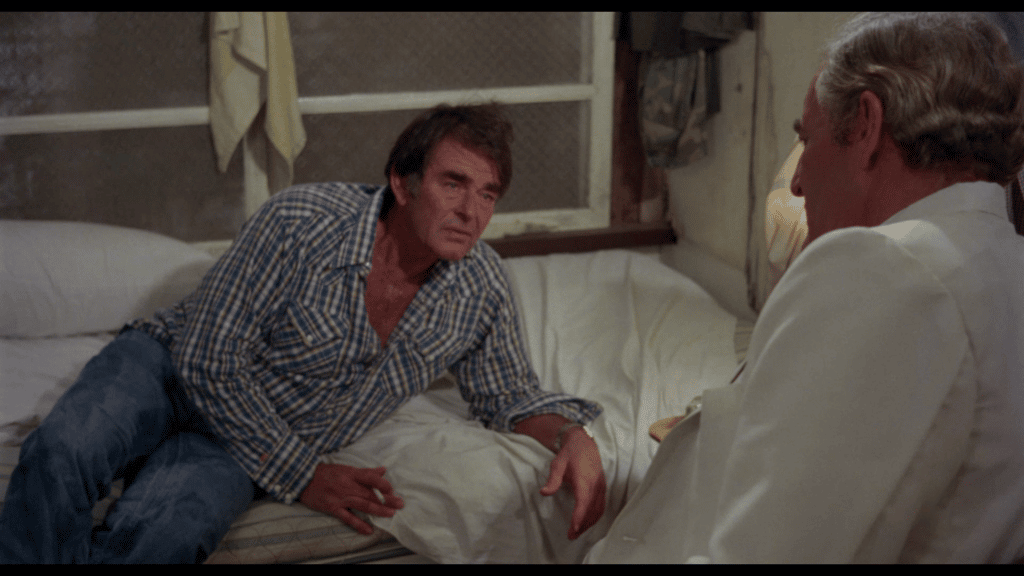

For instance, the nature of the bad blood that exists between Forrest and Larson is never fully explained, though it is hinted at in the dialogue. Larson, played with constantly brooding menace by Purdom, baulks when Jefferson suggests that Forrest should be approached to lead the expedition, and why Jefferson is so concerned with hiring the profoundly sozzled Forrest is anybody’s guess. Later in the film, there is an oblique confrontation between Forrest and Larson, Forrest telling Larson that ‘For two years, I’ve been searching and hunting for you. I thought you were dead’, adding that he was ‘locked in my concrete cell, with only one thought in mind’ for five years prior to this. ‘Somebody had to be the fall guy’, Larson notes, ‘and you drew the short straw’. Larson, it seems, stiffed Forrest on a former adventure, and Forrest fell into the role of patsy. This event presumably led to Forrest’s decline into alcoholism, and his habit of haunting seedy strip clubs. Afterwards, Forrest tells Larson that he ‘didn’t come for the gold. I came for you. So you can start thinking of when, and how’. This declaration of intent, in terms of Forrest’s desire for revenge against his former compadre, finds its payoff in the film’s final sequence; but it is arguably introduced far too late in the narrative to have any kind of import, making it an almost throwaway aspect of the story. A more thorough revision of the script before production could perhaps have led to such thematic threads being more carefully woven into the fabric of the film’s plot.

Whitman is characteristically grizzled in his role as Forrest, exhibiting the same charisma he demonstrates in some of the other low-budget exploitation films he made during the late-70s/early-80s (such as Alberto De Martino’s poliziesco Una magnum Special per Tony Saitta/Blazing Magnums, and Rene Cardona, Jr’s Guyana: Crime of the Century). However, in the early scenes of Invaders of the Lost Gold, Whitman’s character is given little room to breathe, and is simply positioned in a number of scenes in which he is required to drink alcohol – or show the boozy effects of overconsumption.

In one particularly memorable scene, most likely inspired by the opening scene of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) – in which a drunken Willard is shown awaiting new orders in a hotel room in Saigon – Forrest is shown in a hotel room, playing drunkenly with an empty bottle of J&B whisky, that staple of exploitation films of this period: he spins it under his bed, tries to stand it on its neck, and endeavours to use it as a telescope before throwing it at the door when Jefferson knocks on it. The scene is clearly intended to show the alcoholic Forrest ‘bottoming out’ before accepting the chance to redeem himself that is offered by Jefferson’s expedition – but Whitman looks convincingly hammered, to such an extent that it’s difficult to buy Jefferson’s insistence that Forrest join the expedition. (After this scene, the film cuts to the departure of the expedition, a much more sober and purposed Forrest – presumably having cleaned up his act very swiftly – commenting that ‘I hit the skids there for some time, but now things are looking up’.)

Jefferson also uses his daughter, Janice, to encourage Forrest to join the expedition. Janice prowls various seedy nightspots, looking for Forrest. When she finds him, she tells him that she is ‘prepared to talk all night if you’ll listen’, and an elliptical edit implies that she sleeps with Forrest in order to persuade him to accept her father’s proposition. Inevitably, once the expedition is underway, Janice falls for Forrest – in a bizarrely contrived romance between the ageing, albeit charismatic but utterly penniless, alcoholic and Jefferson’s bright, attractive daughter. This leads to a scene of seduction, during one of the expedition’s overnight camps, which feels – for want of a better word – deeply icky.

As Cal, Woody Strode steals many of the scenes in which he appears. Thanks to his height, Strode was always a memorable screen presence, even when slumming it in no-budget productions, and Invaders of the Lost Gold is no exception. (In this film, Strode’s 6’3” stature is in many scenes extended through the tall, straw ten-gallon hat he wears.) Whitman and Strode had worked together previously on a number of films, including Mircea Drăgan’s Oil: The Billion Dollar Fire (1976), also produced by Dick Randall, and Chuck Workman’s Cuba Crossing (1980). The two actors work well together here, a clear sense of warmth underpinning their relationship. Sadly, once the expedition gets underway they have too few scenes together.

Cal is introduced, alongside Forrest, in a local strip club, where the camera lingers over a group of Filipina strippers, their provocative dancing – to the repetitive music on the soundtrack – bathed in red light. A group of American sailors become rowdy and hurl abuse at Cal, their language drenched in unpleasant racial epithets. We see American racism at play, directed by representatives of the US Navy against a man of the same nationality, in a context that is both overseas and predominantly non-white (ie, the Filipino strip club). Cal keeps his cool, maintaining his composure until the inevitable fight breaks out, and Forrest comes to Cal’s aid – though it seems that Cal is perfectly capable of holding his own in hand-to-hand combat, even when outnumbered. Afterwards, Cal observes to Forrest, ‘First time in my life a white man ever helped me out in a fight’. ‘I didn’t like the odds’, Forrest responds. This scene finds its echo later in the film, when during the expedition Cal and Tobachi come to blows in an extended fight scene, the two men seemingly quite serious in their attempts to harm one another. The fight begins after Tobachi sneaks up on Cal whilst the latter sits against a tree, strumming his guitar. However, the brawl ends as abruptly as it started, with Cal and Tobachi laughing with one another fraternally – no overt explanation offered for the shift from violence to good humour.

These two scenes, of male characters bonding in combat, are amongst the film’s most memorable moments – alongside Laura Gemser’s protracted moment of skinny-dipping, which provides the film with its most easily-exploitable sequence, captured in the film’s theatrical posters and video art.

Specifications

Severin Films’ Blu-ray release of Invaders of the Lost Gold presents the film on a region ‘A’ locked disc. The film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, with the feature filling approximately 19Gb of space on the disc.

With a running time of 87:38 mins, the film appears to be uncut. The presentation is based on a 2k scan of unspecified film materials, though would seem to be a composite of more than one source. The optically printed titles sequence, bearing the film’s alternate title ‘Greed’, are in particularly rough shape, with a lack of definition and moderate print damage. However, this soon abates once the titles sequence has ended. The bulk of the film looks very good indeed, with a pleasing level of fine detail and some nicely-balanced contrast levels: blacks are deep and rich, with good gradation into the toe and shoulder. Nevertheless, the (brief) slow-motion scenes suffer from some very prevalent print damage, black scratches and marks in this footage suggesting it is from a positive source rather than the negative. The presentation retains the structure of 35mm film, but sometimes the encode struggles to resolve the grain of the film stock. (This is, admittedly, something that is barely noticeable when watching the film in motion.)

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 dual mono track. This is clear and free of issues, with good range. However, it should be noted that the film’s sound mix is at times funky, with some scenes featuring a jarring mixture of live sound and post-sync dubbing. For example, the scene in which Jefferson attempts to recruit Forrest features Whitman’s dialogue recorded live, whilst the lines of David De Martyn are clearly dubbed.

Extras

The disc includes an interview with Alan Birkinshaw. Entitled ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, this interview runs for 16:33 mins. Birkinshaw talks about meeting Dick Randall, and signing the his contract for Invaders of the Lost Gold on the back of a napkin in the Champs-Élysées. Randall ‘made a couple of quite good pictures, and he made a lot of dubious ones’, Birkinshaw says, adding that Randall could come up with good ideas but usually struggled to ‘execute them brilliantly’.

The film was shot in Pagsanjan, using the infrastructure left behind following the production of Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in that region. Production was scheduled over five weeks, with post-production taking place in London.

Randall reveals that Britt Ekland was to play the role of Janice, but when one of the film’s backers pulled out suddenly, the part was recast owing to cuts to the film’s budget. Glynis Barber was eventually cast instead. Apparently, Whitman and Purdom both thought they were playing the lead role, and would refuse to leave the breakfast table before one another – because they feared this would undermine their authority on the set.

The film was promoted under a number of different titles: Horror Safari, Greed, Invaders of the Lost Gold. Birkinshaw admits: ‘I have no idea what the official title is now’.

Also included as an ‘extra’ are outtakes from Mark Hartley’s 2010 documentary Machete Maidens Unleashed! Hartley’s documentary focuses on the genre films produced in the Philippines. The outtakes presented here feature interviews with Birkinshaw and Corliss Randall, the wife of Dick Randall. These cover much of the same content as the interview with Birkinshaw that is also included on the disc. This extra feature runs for 22:25 mins.

Clearly impeded (in any conventional sense) by the ad hoc approach to its scripting, Invaders of the Lost Gold nevertheless has a great cast who all display a considerable amount of screen charisma, even if the two lead actors (Whitman and Purdom) seem to be acting in separate films in which each has the starring role over the other. It’s a formulaic picture, certainly, with a narrative that stops and starts – sometimes for its most marketable scenes (notably, Gemser’s bout of skinny-dipping), and sometimes simply owing to a lack of momentum – but the charisma of the actors means that it is eminently watchable.

Severin Films’ release of Invaders of the Lost Gold contains a very pleasing presentation of the main feature, and the extra features help to contextualise the production – particularly the new interview with Birkinshaw. The golden rule of exploitation films (ie, ‘if you know, you know’) applies here, and certainly fans of exploitation films of this era will find much to enjoy in this release, though the film’s offkey charms may very well be lost on casual viewers.

For more information on this Severin Films release, please click here.