Reflections on the twilight years of any great artist or company tend to be tinged with sadness and regret, lamenting on how the mighty had fallen, how their latter day work could only serve as a pale reminder of how great things had once been. Conventional wisdom would seem to dictate that this is how we should look upon Hammer Films post-1970. With the loss of financial backing from long-standing supporters Warner Bros, and a cinematic climate which was rapidly growing ever further beyond the now-somewhat quaint conventions of the British production house, the post-60s outlook seemed bleak for the stalwarts of Gothic horror; and, almost 50 years later, the critical consensus on the films they made in their final decade tends to be less than glowing.

For myself, though, Hammer’s 1970s output has always been a source of endless fascination, and I find myself returning to their films from that period above all else. Sure, a large part of this is sentimental attachment, as many of the first Hammer Horror films I saw on late night TV screenings in my youth were from that era; and, as a hormonally-charged young teen, I was unsurprisingly more drawn to later Hammer due to its much heavier blood and nudity quota. I can appreciate why many feel that these efforts to keep up with the more permissive times were out of step with the films on which the company made its name (not unlike that other British cinema institution, the Carry On series, in that same decade), yet I personally don’t believe Hammer’s later films betray the spirit of what went before. For one, we can hardly accuse 70s Hammer of besmirching the company’s good name, as Hammer’s name had never been that good in the first place as far as respectable society was concerned. Much as these were films which I tiptoed downstairs to watch on TV in the wee small hours, doing my best to make sure my parents didn’t hear me, I gather that those who went out to see Hammer productions on release – and, indeed, many of those who worked on the films themselves – tended to do so in the hopes that others wouldn’t find out, feeling some unseen eye of judgement upon them, knowing that they should know better than to associate themselves with that sort of film. This, I suppose, is how the term ‘guilty pleasure’ came to be; but as far as I’m concerned, the pleasure almost always outstrips the guilt when it comes to Hammer.

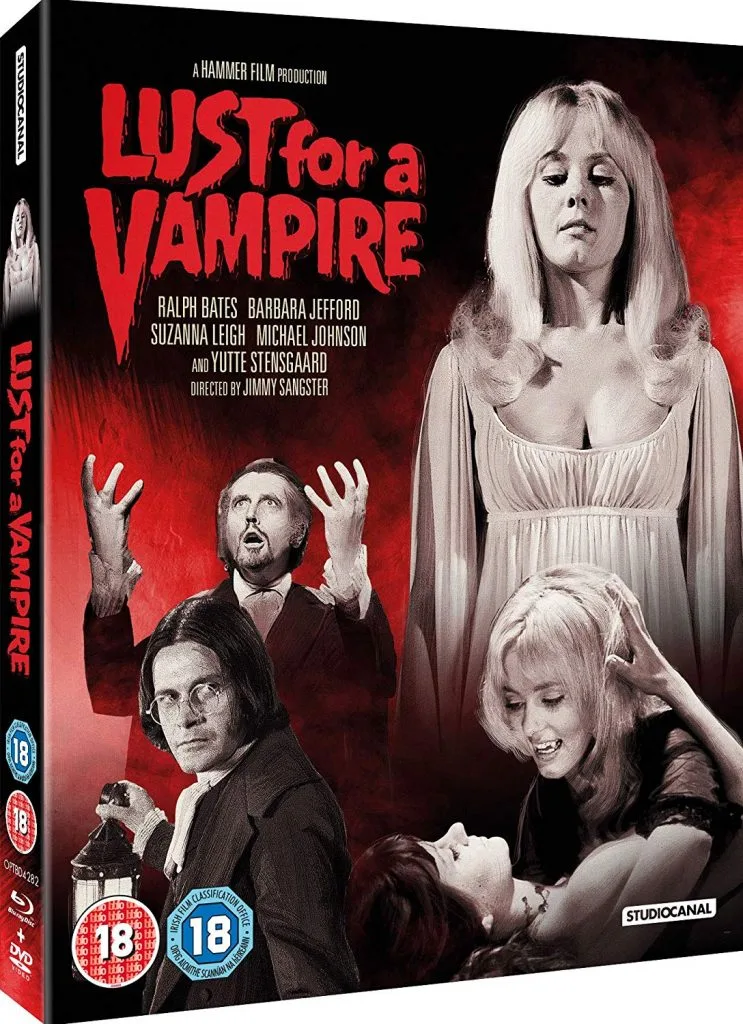

Released in January 1971, Lust For A Vampire might well be a perfect encapsulation of the state of things in Hammer’s House of Horror at the turn of the decade. It’s still essentially playing in the period-set Gothic arena which had been the company’s staple since The Curse of Frankenstein and Dracula (AKA Horror of Dracula). However, Hammer’s linchpin thespians Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing are notable by their absence, with a largely younger ensemble taking centre stage, in hopes of hooking the hip and groovy young cinemagoers of the time. Of course, youngsters weren’t the only target demographic, as should be abundantly clear from Lust For A Vampire’s central conceit: a lesbian vampire in an all-girls boarding school. Yep, pretty much sounds like a dirty old man’s dreams come to life, and to a large extent that’s just how the film plays out. This, it seems, hadn’t always been the plan: as is detailed in the extras of this new Blu-ray, the original title of Tudor Gates’ script had been To Love A Vampire, and the writer had intended a more genuinely romantic and heartfelt film, without quite so much gratuitous nudity and sleaziness as the final product delivers. Again though, while some Hammer traditionalists might be dismayed at how Lust For A Vampire is far less classy than it might have been, it’s hard to imagine it being anywhere near as much fun with the sleaze dialled back.

The second instalment in Hammer’s unofficial Karnstein trilogy (coming after 1970’s The Vampire Lovers, and before my personal favourite Hammer film, 1971’s Twins of Evil), Lust For A Vampire sees the return of J Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla/Mircalla Karnstein, this time around portrayed by Yutte Stensgaard. It seems a shame that Ingrid Pitt, who played the role so memorably in The Vampire Lovers, opted not to come back for the sequel, but – as, again, is argued in the extras – a case can be made for Stensgaard being a far better fit for the role as written; namely, she actually does look and seem like a demure, innocent young woman whom no one would ever suspect of being a supernatural predator in disguise. Inexplicably back from the dead some years after the events of the previous film (as ever, best not to get too hung up on the technicalities there), Mircalla finds a veritable smorgasbord served up in the idyllic country estate that houses scores of 18-21 year old women (at least, let’s hope they’re all in that age group). Arriving around the same time is Richard Lestrange (Michael Johnson), a novelist who specialises in the fantastical and macabre, who is intrigued by local tales of vampirism, but is compelled to stick around by the abundance of pretty young ladies at the school, where he soon slyly acquires a teaching position. Mircalla shortly becomes the object of obsession not only for Lestrange, but for fellow teacher Giles Barton (Ralph Bates), a historian specialising in the history of the Karnstein family, with an inkling of Mircalla’s big secret.

The romantic angle which Gates’ script reportedly took might have been more in evidence in the final film had someone other than Johnson been cast as Lestrange. (It’s suggested Gates intended the character as a stand-in for LeFanu himself, which might have lent a meta quality to proceedings, implying Carmilla’s writer drew on his own life experience.) Not the most dashing of leading men, Johnson brings very little charisma to the role, mostly coming off as a manipulative, lecherous predator. Obviously this leaves us with no problem believing he would become infatuated with Stensgard’s Mircalla; but the trouble is, she’s meant to requite his feelings. Even if we disregard that her character is a lesbian, it’s very hard to believe that anything about this man would draw her in, much less truly win her heart as he’s supposed to.

Of course, it’s screamingly obvious within the first few minutes alone that director Jimmy Sangster and producers Harry Fine and Michael Style are far less interested in plausible character development than they are in making the most of the X certificate, whose rules had been relaxed by the BBFC just around the time Lust For A Vampire went into production. An early dorm room sequence might have been aiming for some sort of record for the most bare breasts shown in the shortest amount of time, and while it isn’t necessarily wall-to-wall nudity and girl-on-girl action from there on, they make sure to throw in the odd bit every so often – along with a more generous splash of the Kensington Gore than usual – just to maintain the viewer’s interest. This proves somewhat necessary as the plot grows ever more meandering from the halfway point, many half-baked story threads left dangling, gradually trudging toward the inevitable torch-and-pitchfork finale that had long since been the norm for Hammer. You have to feel a bit sorry for many of the supporting players, most notably Suzanna Leigh as the school mistress Janet Playfair, who’s doing her best with what’s given to her, but ultimately has very little of real significance to do.

So, should we look upon Lust For A Vampire as nothing more than a feeble attempt by an ailing company to keep up with the times, yet at once descending into pure cliche and inadvertent farce? That certainly wouldn’t be an unreasonable reaction. However, we might just as easily embrace the arch camp absurdity and bald-faced trashiness, and just have fun with it, which is surely the desired reaction. There’s really no sense in complaining a movie isn’t high art when it’s clear that this was never the intention in the first place. Look no further than Ralph Bates’ performance; I find it hard to fathom that this role had originally been earmarked for Peter Cushing, as Bates brings a simpering, laughable quality to the role that it’s hard to imagine from the elder Hammer icon. It’s said on the extras here that Bates didn’t particularly like the project and had little real investment in it, so perhaps his camping it up reflects his disdain for the whole endeavour; nonetheless, it is entirely in tune with Lust For A Vampire’s silly, sleazy song.

There can be little question that Lust For A Vampire is the weakest of the Karnstein movies, not least because Yutte Stensgard is nowhere near as commanding a central presence as Ingrid Pitt in The Vampire Lovers, or Mary and Madeiline Collinson in Twins of Evil; yet as the most unabashedly raunchy and low brow chapter, it sums up the spirit of the trilogy quite nicely. Moreso than this, it’s also liable to leave us wondering why, after literally countless Dracula movies in the years before and since, we’ve still yet to see many more fully-fledged big screen adaptations of Carmilla. Given the recent push for greater female and LGBT representation in cinema, one would think that now’s as good a time as any for J Sheridan LeFanu’s vampire anti-heroine to have her day in the sun, as it were.

Lust For A Vampire is released to Blu-ray and DVD on 12th August, from Studiocanal.