As someone who writes about films, it’s always a telling moment when you find yourself approaching a particular review with trepidation. Given that, at the time of writing, pretty much an entire week has passed since I saw Assassination Nation at Celluloid Screams 2018, there’s no denying that this is one such film I feel a little anxious about tackling. Much of the audience at the Saturday night screening in Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema appeared to react very enthusiastically indeed to writer-director Sam Levinson’s film, and I gather it’s been inspiring similar responses in its many festival screenings since premiering at Sundance. It’s a film which goes out of its way to do things by extremes, from its loud and brash colour schemes and soundtrack, to its hyper-kinetic camerawork and editing, and perhaps above all else its ultra-topical, ultra-timely commentary on the contemporary climate of sexual politics, social media, data hacking and the current wave of feminism. In tackling subject matter that is so close to the bone in 2018, Assassination Nation seems specifically designed to be scoured over academically, which can make it a bit harder to simply address its merits as a piece of filmmaking; and it plays a tricky balancing act between its ‘woke’ worldview and its aspirations toward vintage bad girl exploitation thrills, which I’m not sure it entirely succeeds in. This, however, is not to deny that Assassination Nation is a striking piece of work that merits a wide audience and widespread discussion.

As someone who writes about films, it’s always a telling moment when you find yourself approaching a particular review with trepidation. Given that, at the time of writing, pretty much an entire week has passed since I saw Assassination Nation at Celluloid Screams 2018, there’s no denying that this is one such film I feel a little anxious about tackling. Much of the audience at the Saturday night screening in Sheffield’s Showroom Cinema appeared to react very enthusiastically indeed to writer-director Sam Levinson’s film, and I gather it’s been inspiring similar responses in its many festival screenings since premiering at Sundance. It’s a film which goes out of its way to do things by extremes, from its loud and brash colour schemes and soundtrack, to its hyper-kinetic camerawork and editing, and perhaps above all else its ultra-topical, ultra-timely commentary on the contemporary climate of sexual politics, social media, data hacking and the current wave of feminism. In tackling subject matter that is so close to the bone in 2018, Assassination Nation seems specifically designed to be scoured over academically, which can make it a bit harder to simply address its merits as a piece of filmmaking; and it plays a tricky balancing act between its ‘woke’ worldview and its aspirations toward vintage bad girl exploitation thrills, which I’m not sure it entirely succeeds in. This, however, is not to deny that Assassination Nation is a striking piece of work that merits a wide audience and widespread discussion.

The action plays out in a small American town called Salem (too on the nose? We’re barely getting started). Our central protagonists are a quartet of popular, sex-positive high school girls, Lily (Odessa Young), Sarah (Suki Waterhouse), Em (Abra), and Bex (Hari Nef), and like a large percentage of their age group, their lives revolve around the friends, their phones, and near-constant partying. However, the party in Salem takes an unexpected turn when the personal data and internet history of various high profile local figures are released online by an anonymous hacker (by which we mean, you know, someone who’s hiding behind anonymity, not that they necessarily are… forget it). That which is revealed prompts outrage among the adults, ending careers and ruining lives overnight; whilst the reaction from local teens, our heroines included, is almost nothing but ‘LOLs.’ Yet it becomes apparent that the hack isn’t going to stop there, and soon enough literally everyone in Salem has their data leaked for all the world to see. The secrets that are now out in the open lead to hysteria and violence, a good portion of which winds up being directed towards the central quartet, as like any young people of note, they too have their share of skeletons in the closet. Yet as tempers flare ever more intensely, Salem’s townsfolk – the white males in particular – grow ever more anxious to find out who the hacker is, and bring them to justice. Of course, their particular definition of justice looks rather more like the wild west, and they’re just itching to get some lynching done – but our heroines are not about to be taken down that easily.

Full disclosure: I come to this film as a straight white cisgender male nearing the end of his thirties. This being the case, I’m acutely aware that I’m far from the primary intended audience of Assassination Nation, and by extension it’s certainly no accident or mere coincidence that I found much of it exhausting. In common with many of the most celebrated and/or reviled young rebel movies of the past two decades – Natural Born Killers, Fight Club, most recently Spring Breakers – Levinson’s film goes out of its way to overstimulate the audience with a constantly roving camera, a throbbing soundtrack, and machine-gun dialogue in an aggressively modern vernacular. The core quartet are clearly intended as inspirational figures for the young audience, women in particular. Certainly all of them have their flaws and make their share of mistakes which the film does not attempt to gloss over, but they own these, refusing to play the victim or accept the abuse that is hurled in their direction. They maintain this attitude from the Heathers/Mean Girls-esque beginnings, through to a more intense, emotional yet still grounded second act, all the way through into a frenzied, ultra-violent conclusion straight out of a Purge movie.

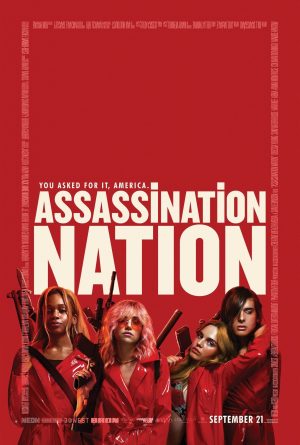

This progression from reasonably plausible small town drama into quasi-apocalyptic shoot-’em-up delirium seems key to the appeal of Assassination Nation; certainly it’s been deemed the main selling point, given that the film has been marketed almost entirely on images of the young leads in their eye-catching red raincoats holding guns. The thing is, while the film plays out in a ‘heightened’ fashion (pardon my use of that overused modern film criticism buzzword, typically utilised by poorly-read writers trying to deny genre), events still play out in a comparatively grounded and plausible fashion; or, at least, grounded and plausible by comparison with these stranger-than-fiction times America is currently living through. This being the case, when the final act centres on our oppressed and scapegoated young women fighting back by literally taking up arms, questions are invariably raised about whether Assassination Nation is truly advocating such a course of action; no small thing given what a sensitive subject gun control has also been in America in recent years. Even so, it’s not hard to pinpoint a shift in tone about two thirds in when the film makes clear it’s side-stepping into outright fantasia, with slasher/home invasion horror elements soon giving way to over-the-top action. And, of course, this is hardly the first film to balance a serious message of female empowerment with stylised theatrics and fantasy violence; take just about any women in prison or rape revenge movie from decades gone by.

It’s also curious to note that, while Assassination Nation presents itself as unabashed extreme cinema setting out to push as many buttons as possible – take its early ‘trigger warning’ montage, the focal point for the film’s first trailer – it actually rather feels like it’s holding back in some respects. Certainly guns, sexism, homophobia and fragile male egos are at the forefront, but racism doesn’t seem to come to the forefront despite the presence of a black lead in Abra’s Em. Transphobia is curiously diluted too, given that we also have a trans lead in Hari Nef’s Bex; who, while she absolutely faces hostility and bigotry, is still unanimously referred to throughout as a ‘she’ and by her chosen name, even by those baying for her blood. It is absolutely laudable that the film and its central characters do not treat Bex as anything but another girl (indeed, the fact that she’s trans isn’t even mentioned until some ways in), yet it seems a little self-defeating to imply that their belligerent, ignorant oppressors would still play nice about it even when they’re trying to kill her.

It’s also curious to note that, while Assassination Nation presents itself as unabashed extreme cinema setting out to push as many buttons as possible – take its early ‘trigger warning’ montage, the focal point for the film’s first trailer – it actually rather feels like it’s holding back in some respects. Certainly guns, sexism, homophobia and fragile male egos are at the forefront, but racism doesn’t seem to come to the forefront despite the presence of a black lead in Abra’s Em. Transphobia is curiously diluted too, given that we also have a trans lead in Hari Nef’s Bex; who, while she absolutely faces hostility and bigotry, is still unanimously referred to throughout as a ‘she’ and by her chosen name, even by those baying for her blood. It is absolutely laudable that the film and its central characters do not treat Bex as anything but another girl (indeed, the fact that she’s trans isn’t even mentioned until some ways in), yet it seems a little self-defeating to imply that their belligerent, ignorant oppressors would still play nice about it even when they’re trying to kill her.

All this having been said (and believe me, there’s plenty more that could be said about the film), there can be little question that Assassination Nation is a powerful and effective piece of work. After all, any film that leaves one with so much to say and say much to think about is always going to be noteworthy, for better or worse; and the fact that, even after a week of reflection and over 1200 words typed on the subject, I’m still not 100% sure how I feel about the film, only seems to confirm that Sam Levinson and company have succeeded in what they set out to do. It’s a movie that some are going to love and some are going to despise with an equal passion, but whichever side of the fence you fall on, it’s unlikely to leave your mind for some time thereafter. As such, it’s absolutely a film that I recommend everyone goes to see; your conclusions, as ever, will be your own.

Assassination Nation just screened at Sheffield’s Celluloid Screams; our thanks to all at the festival. It’s also set to screen at Abertoir Horror Festival in Aberystwyth, Wales, before getting a wide UK cinema release on 23rd November.