The daikaiju (or, if you’re a bit less ostentatious, giant monster movie) has always offered a handy, audience-friendly way for filmmakers to address big fears. As countless books on the subject will tell us, Godzilla served as a cathartic expression of post-Hiroshima/Nagasaki angst for Japan, and the ensuing franchise has addressed broader concerns about ecology, corporate greed, and the many various abuses of power which bring down nature’s wrath upon mankind. Since then, Cloverfield dealt with the traumas of 9/11, the Godzilla reboot evoked the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011, and Kong: Skull Island touched on both Vietnam and, by inference, the subsequent US-led invasions made in the name of the War on Terror. All huge, large-scale horrors which had a devastating effect on large numbers of people. However, it’s rather less common that we see giant monsters used as a symbol for troubles of a more intimate, personal nature, which would seem to be what writer-director Nacho Vigalondo is aiming for with curious genre-bender Colossal.

Anne Hathaway is Gloria, a former professional writer whose career and life seems to be on the skids since losing her job. Some write-ups have described her as a ‘party girl,’ but let’s be more direct about this; she’s an alcoholic, or at the very least on the brink of alcoholism, frequently pulling all-night benders in the company of people she barely knows. Naturally this puts a strain on her relationship with her significant other Tim (Dan Stevens), and shortly after we meet the couple he announces he’s kicking her out of the apartment. With no money and nowhere else to go, Gloria returns for the first time in a long time to the anonymous town where she grew up, shacking up in the now-empty house that was once her home. Soon she bumps into an old school friend Oscar (Jason Sudeikis), who not long thereafter offers her work at his bar; helpful for Gloria’s money problems, but perhaps less helpful for her drinking problem. However, these matters soon seem insignificant when news breaks of a giant monster suddenly appearing in Seoul. Naturally, the world is shaken to its core by this turn of events, but it proves to be a particular shocker for Gloria, as she comes to the somewhat startling realisation that she is in some way connected to this creature, and in control of its movements.

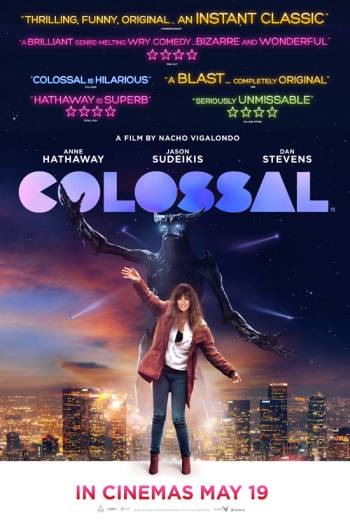

I should think it goes without saying that Colossal is something of a peculiar film. Not only is the concept pretty bizarre, it’s also quite far from what you might anticipate in execution. Whilst it opens off with bombastic music and sweeping aerial shots which would seem at home in any big budget giant monster epic, the film very quickly reverts to a much more grounded style with black comedy leanings. Even so, it strikes me as rather misleading that, on the UK poster to the left at least, Colossal is largely promoted as a comedy, with review quotes emphasising its hilarity. I suppose it’s inevitable that marketing people would seek out the simplest angle on which to sell a film this unorthodox, but for one, despite its clear and unabashed absurdity, Colossal is never laugh-out-loud funny. More pertinently, the film takes a somewhat unexpected shift in tone midway which sends it in a considerably darker direction.

It would be giving too much away to explain the circumstances behind this tonal shift, but I do feel safe in saying it’s this latter portion of the film which is most likely to divide opinion, and it may be deemed to muddy the waters somewhat as far as to whatever it may be that Colossal is trying to say. Early on, given the emphasis on Gloria’s near-constant drinking, her proclivity for bullshitting, and the affect her alcohol abuse has on her memory, it’s easy to take the giant monster as a symbol for her addiction. However, as things develop, the theme seems to be a broader look at the nature of control; both one’s own self-control, and the lengths to which some will go to control others. As Gloria finds herself a woman alone in the company of men once she returns to her home town, the film invariably lends itself to feminist readings, and by extension it’s very easy to see it inspiring foaming-at-the-mouth rants from so-called men’s rights activists.

So, if it’s not quite funny enough to be a comedy, too cartoonish to be a drama, and yet a little too much of both of those things to be a fully-fledged monster movie (watching the end result, the early legal action against the film by Toho seems all the more absurd), then does this mean Colossal won’t wind up pleasing anyone? Well, it’s fair to say if you go in expecting another Pacific Rim, you’re going to be a trifle let down, as there’s no mistaking this is a comparatively low budget affair, with only brief glimpses of city-stomping mayhem, and a monster which – gasp! – has even less screentime than Godzilla had in the Gareth Edwards movie. However, if you go in with an open mind (much as we should every time we sit down to a movie!), then you may find, as I did, that this unusual blend of genre tropes is inventive and pleasing. Hathaway, as ever, is an endearing lead, and happily she’s de-glammed enough to convince in the role, whilst Dan Stevens does another 180-degree turn from his work in The Guest and TV’s Legion in his most straight-laced, enjoyably square performance yet. The real surprise is Jason Sudeikis, who proves himself capable of a lot more than the largely two-dimensional comedy parts he’s generally had so far. Bit of a shame, though, that Tim Blake Nelson is squandered a little in a character that never winds up serving much purpose, whilst Austin Stowell is a little too square-jawed, fresh-faced and buff to be entirely believable as a full-time drinker.

Colossal might not be an instant classic, but it’s an enjoyable movie of the kind we tend not to see as often as we’d like these days: an original, mid-budget production which takes some genuine risks and attempts something new. And it’s a laudable effort, even if it doesn’t quite land a bullseye.

Colossal is in UK cinemas now.