Negotiating the relationship between art and artist can be a tricky business at times. For many, approaching any new movie from Mel Gibson is going to be a tough pill to swallow given the man’s many public disgraces and personal views which don’t sit well with some of us. But even if we try to take the filmmaker’s real life persona out of the equation and approach Hacksaw Ridge purely as a new addition to his body of work, it may seem fraught with contradictions right away. Throughout both his acting career and his work behind the camera on Braveheart, The Passion of the Christ and Apocalypto, Gibson’s fascination with violence has always been front-and-centre, and many would go so far as to suggest he fetishises combat; and yet, here he is taking on the story of a devoutly Christian pacifist who steadfastly refused to engage in violence during World War 2, despite having enlisted in the army of his own accord. Indeed, at a glance Desmond Doss’s story would also appear somewhat self-contradictory. So in a curious way, it is a very fitting tale for Gibson to tell, and one that cuts directly into the clash between religious conviction and rampant bloodlust which runs throughout his filmography.

Andrew Garfield takes the lead as Doss. Following a brief battlefield montage intro which makes Peckinpah’s use of slo-mo seem understated, we’re taken back to the young man’s childhood, and shown how a number of key events would inform the man he grew up to be: namely, a fight with his brother which almost ended in tragedy, and then fifteen years later his first experience of saving a live after coming to the aid of a man involved in a car accident. On taking said man to the hospital, Doss falls in love at first sight with nurse Dorothy (Teresa Palmer), and pursues her with a slightly alarming blend of virginal naivety and stalkerish persistence. This approach proves effective, and soon enough Doss seems happier than he’s ever been; but America is entering World War II, and all able-bodied men of his age are signing up. Feeling honour-bound to serve his country, Doss signs up with the intention of serving as a medic, but once he reaches training it doesn’t take long for him to find himself at odds with all those around him over his somewhat unusual insistence that, while he will undertake all other aspects of military training, he will not bear arms or take a human life.

We all know how Hollywood movies tend to adhere to the classic three-act structure, and in this instance those acts couldn’t be more clearly divided. (As South Park told us so long ago, say you want about Mel Gibson, but the son of a bitch knows story structure.) Act One gives us Doss’s childhood and burgeoning romance with Dorothy, all painted in a largely idyllic fashion despite his troubles at home with his father (Hugo Weaving), a World War 1 survivor whose memories of the battlefield have left him alcoholic and clearly suffering from undiagnosed PTSD. Act Two, unsurprisingly for a war movie, is pretty much Full Metal Jacket, as Doss enters into his military training under Sgt Howell (Vince Vaughn) and Captain Glover (Sam Worthington), who endeavour to bully him into quitting once they realise he will not budge on his pacifism. Act Three, then, takes us to the battlefield of the title in Okinawa, as the battalion ascend the cliffs of Hacksaw Ridge and march on the Japanese, and from that point the remainder of the film is pretty much one long, unrelentingly brutal battle sequence; but an unusual one, in that its focus is as much on Doss’s dogged efforts to save the wounded as it is on the carnage unfolding around him.

It all looks and sounds like a pretty standard Hollywood war movie for the most part, but it’s the character of Doss and Garfield’s performance in the role which gives Hacksaw Ridge a very different feel. Gibson’s protagonists in the past have tended to be square-jawed badasses, notably Braveheart’s William Wallace and Apocalypto’s Jaguar Paw; hell, even his Jesus ruthlessly kills a snake under his sandal at one point. It’s unusual, then, for him to put the spotlight on someone so far from a conventional manly man. Garfield’s a bold actor, and he’s not afraid to make his Doss gawky, awkward and resolutely non-macho, and while this does make his courtship of Dorothy a little unconvincing (honestly, the whole love story is the least effective element of the film), it allows for an unconventional representation of courage and conviction. Though treated as a dissident, Doss is never a smart-ass, never disrespectful or aloof among his peers, nor does he try to convert anyone to his point of view.

In this respect, Hacksaw Ridge is able to effectively explore questions of faith without, for the most part, feeling like Christian propaganda; not something that was necessarily the case in Gibson’s other faith-oriented movie, The Passion of the Christ. Indeed, the film in many respects follows a similar path to The Passion, as both films take a degree of foreknowledge for granted (much as The Passion didn’t retell the story of Christ at length, Hacksaw Ridge doesn’t detail America’s entry into WW2 too heavily, with Pearl Harbor only getting a brief mention), then they present us with a man and his principles, and show us the extent to which he will stand by them as he endures unimaginable torment. The difference, of course, is that we go into this knowing full well that Doss will come out alive on the other end of it, to ultimately become the first conscientious objector to be awarded the Medal of Honor. Even so, Hacksaw Ridge doesn’t really come off as a movie about religious belief, so much as it is about personal conviction. Gibson may believe that Doss’s strength under fire came directly from God, but the film never asks the audience to take this as gospel (pun absolutely intended), even if it does show Doss’s faith spreading to his fellow soldiers, implying that it helped them persevere. Call that God’s power if you will, but we might just as easily call it the strength of the human spirit; which naturally begs the question of whether there’s any difference between the two.

All this having been said, while Hacksaw Ridge tackles some interesting and fairly challenging concepts, it does so within a pretty standard, mainstream-friendly format. As is the norm for Gibson, some of the more light-hearted moments come off pretty goofy, and particularly in the earlier scenes there’s an undeniably hackneyed quality to the set-up, notably when Doss learns his key life lessons: the textbook look of revelation on his face as he realises violence is wrong, that he could become a medic, that a nurse he’s never spoken to is the woman he’s going to marry. This initial conventionality might be Gibson’s way of putting us at ease before throwing us into no man’s land, and as might be expected the climactic battle sequences really don’t hold back, with blood gushing, guts spraying and limbs flying all over the shop (much of it clearly CGI, which does tarnish the verisimilitude here and there). As might also be expected, it’s here that the contradictions at the heart of Hacksaw Ridge are at their most pronounced, as while the film may celebrate Doss’s pacifism and endeavour to show the full horror of war, there’s no avoiding a sense of testosterone-fuelled joy in much of the bloodshed, particularly given that the Japanese are for the most presented like boogeymen.

Once again, separating art from artist is difficult for some of us, particularly when it comes to people who have publicly shamed themselves the way Gibson has. While this isn’t the time or place for an in-depth discussion of film and politics (I may get into that in detail another time), I will note that it seems to be growing ever more commonplace that, as soon as an artist – or indeed, any public figure – has said and/or done something deemed disgraceful, there will be those calling for this person to be effectively stricken from the cultural record and no longer allowed a place at the table. Undoubtedly there are some instances where this is unavoidable (no one listens to Lostprophets anymore, right?), but I’m not sure that’s the case with Gibson. Certainly I’m not about to defend some of the things he’s said or done, but at the same time I cannot dismiss the impact he has had on modern cinema on both sides of the camera. I do not believe that agreeing with an artist’s personal beliefs and life choices is a prerequisite for appreciating their work, and I hope – though I’ll admit this one may be a stretch – that said art might present a common ground on which people of opposing worldviews may learn to communicate and co-operate. As such, I welcome Hacksaw Ridge as a return to form – indeed, a redemptive work – for Gibson, and look forward to seeing where his directorial career will go from here.

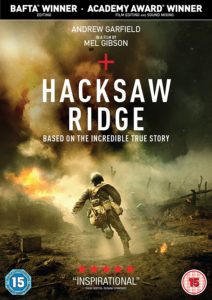

Hacksaw Ridge is out in the UK on DVD, Blu-ray, 4K UHD, Steelbook and digital download on 22nd May, from Lionsgate.