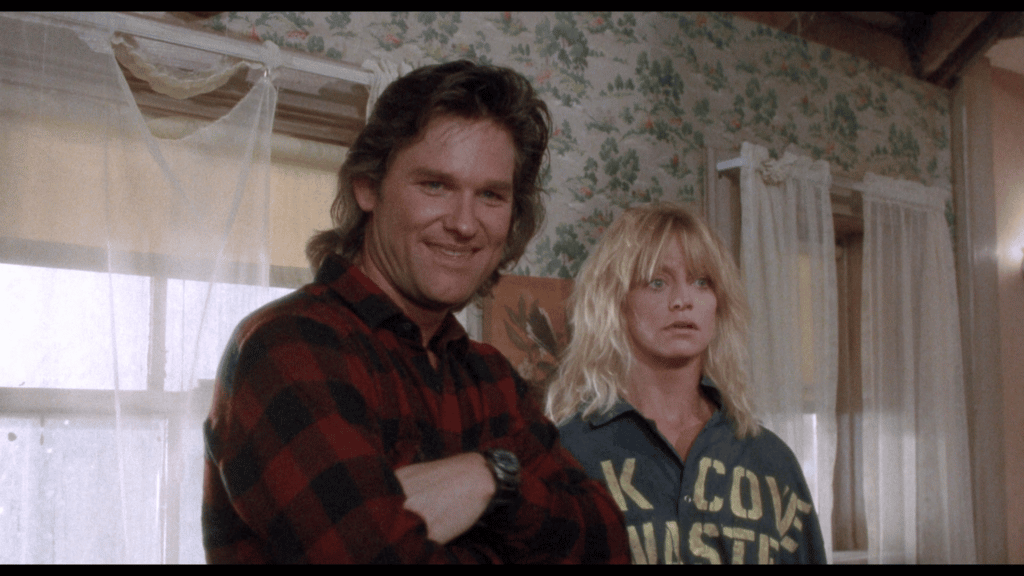

A mid-80s comedy about the charming pastime of gaslighting, Overboard is, in retrospect, an extremely… odd Hollywood picture, whose more bizarre elements are carried by the charm of its lead performers, Hollywood golden couple Kurt Russell and Goldie Hawn. It’s a film that seems an off-piste choice for Severin Films to release on Blu-ray, but their disc of Overboard offers a welcome chance to revisit a Hollywood picture that developed a strong cult following in the years that followed its theatrical release.

In Overboard, Goldie Hawn plays Joanna Stayton, a privileged and obnoxious socialite who is married to Grant Stayton III (Edward Herrmann). Whilst the yacht is anchored close to the town of Elk Cove, Oregon, Joanna hires local carpenter Dean Proffitt (Kurt Russell) to remodel her wardrobe. Proffitt designs a wondrous shoe closet, but Joanna is dissatisfied because he has used the wrong wood, and refuses to pay him the $600 dollars she owes.

One night, Joanna falls overboard whilst searching for her wedding ring. She is rescued and taken ashore, but is suffering from amnesia. Grant visits her in the hospital, but seeing an opportunity to flee from his married life and dally with starlets on the coast of L.A., he claims not to recognise Joanna.

Proffitt, a widower with four distinctly wild sons, sees a golden opportunity: by claiming Joanna to be his fictional wife, Anna, and tying her to a month of domestic chores, he can teach the snooty millionaire a lesson in humility whilst also getting some recompense for his unpaid labour aboard the yacht. The school has also threatened to have Proffitt’s sons taken from him, believing that as a single father he is unable to cope with the responsibilities of raising them: by recruiting ‘Anna’ as his sons’ ‘mother’, Proffitt hopes to stave off an investigation into his domestic situation.

An impractical woman used to being waited on hand and foot (by her butler Andrew, played by Roddy McDowall), Joanna struggles with the household chores at first, and baulks at the behaviour of the children. She sees a disjuncture between her expectations and the reality of her life in the Proffitt household, though her amnesia prevents her from understanding why this is.

However, Joanna soon develops strategies for coping, and the house evolves from a hovel to a home. She also develops feelings for the children, treating them playfully and kindly, even defending them when a teacher unfairly chastises them based on their reputation for bad behaviour. She realises the honesty and integrity of Proffitt, an unpretentious labourer; and she helps him realise his dream of building and opening a unique crazy golf course – which soon becomes Elk Cove’s main attraction.

However, pushed by Joanna’s mother, who wonders what has happened to her daughter, Grant commands the yacht be returned to Elk Cove, and begins a search for his wife. But will Joanna return to her privileged existence, or will she choose to stay with the humble Proffitt clan?

Overboard establishes Joanna’s outrageous haughtiness from the outset. Hawn plays the character with a high society accent, and early in the picture there’s a wonderful moment in which Joanna’s highfalutin ways are deflated when she is served caviar by Andrew. (The caviar does not meet her required standards.) ‘Caviar should be round and hard, and of adequate size’, Joanna says, seemingly blissfully unaware of the Finbarr Saunders (Fnarr-Fnarr) levels of double entendre in her monologue, ‘And it should burst in your mouth at exactly the right moment’. When Joanna chastises Dean for making an incredibly impressive rotating shoe cupboard in the ‘wrong’ wood (Dean has used oak – not Joanna’s preferred cedar), she refuses to pay him, telling Dean that ‘The job was not done to my satisfaction’. ‘I got news for you’, Dean fires back, ‘No job will ever be done to your satisfaction’.

Meanwhile, Dean is depicted as a man-child, with a similar level of emotional maturity to his rabid sons – the boys are introduced when a teacher runs out of Dean’s home, Dean telling her that his sons are ‘going through an arson period’ – and an equivalent lack of grace. ‘I’ve been doing this kind of shi… er, work for years’, he tells Joanna when he boards the yacht to remodel her wardrobe. (‘I doubt if he’s even housebroken’, Joanna grumbles in a telephone conversation to her mother, unaware that Dean can overhear her conversation – which kickstarts his initial enmity towards her.) However, in the film’s early scenes Dean’s rough proletarian exterior is undercut when he demonstrates a hidden artistic flair: an aptitude for carving ornate sculptures using a chainsaw, which comes into play later in the film, when Dean tells Joanna of his desire to build a crazy golf course in which each hole is housed within a sculpted representation of iconic buildings or natural formations. (The film suggests a disjuncture between the artistic aspirations of Dean and his deeply blue collar existence – moonlighting at a fertiliser factory.)

Where Dean teases out of Joanna an ability to act in a nurturing, maternal manner – and to engage in domestic chores – Joanna exerts a similar influence on Dean, providing him with the confidence and support to enable him to pursue his dream. Fundamentally, it seems, Joanna’s problem was predicated on too much of the good life and not enough activity: ‘You’re so bored you got to make up things to bitch about’, an angry Dean tells her after she refuses to pay for the wardrobe remodel on the yacht. (In response, the yacht’s crew, who have heard Dean’s furious response to Joanna, begin to cheer.)

When Joanna falls overboard and finds herself, suffering from amnesia, in Elk Cove’s hospital, she initially speaks in the clipped RP-like tones of New York’s privileged classes. (‘I don’t know who I am’, she says after being placed in a psychiatric ward, ‘but I’m sure I have a lawyer’.) Though she does not know who she is, her haughtiness alienates both the hospital staff and the sheriff, who are keen to place her with Proffitt when he turns up at the hospital and says that Joanna is his missing wife. (‘Well, he seems to like you, and he’s a nice guy’, the sheriff tells her when Joanna says that she doesn’t recognise Proffitt as her husband.) Proffitt takes delight in building a backstory for Joanna that undercuts her high society socialisation: he tells her that her mother was an alcoholic who died of cirrhosis of the liver, and her father is a jailbird. As the film progresses, and as she becomes more accustomed to life with Proffitt, her accent and dialect evolve and become more proletarian.

The film trades on two familiar archetypes from Hollywood films: the spoilt ‘ice queen’, and the incompetent, irresponsible (single) father. (Both are equally negative.) Overboard throws these two types together, allowing them to clash within the context of the chaotic Proffitt household: what results is a process of growth for both Joanna and Proffitt. Some aspects of the film seem outrageous to modern sensibilities: at one point, Dean convinces Joanna that a huge, short dress belongs to her, and tells her that they slept together on their first date. ‘I’m a short, fat, slut’, Joanna weeps. (Can one imagine a film scripted by a male writer getting away with that line today?)

Given some of the oddball sexual politics on display in Overboard (they were oddball at the time, it has to be said – not necessarily solely through a post-#MeToo lens), it might be tempting to assume that the film’s narrative voice is male. However, Overboard was scripted by a female writer, Leslie Dixon (who, coincidentally, is the granddaughter of the great documentary photographer Dorothea Lange – a personal hero of mine – and the artist Maynard Dixon). Earlier in the year, the Dixon-scripted Outrageous Fortune had been a huge hit, and Dixon was approached to write another picture with the aim of achieving a similar sense of economic success. (Overboard recouped its budget and made a small profit, but became something of a cult favourite on home video and via television screenings.)

Dixon’s inspiration was a true case, of a woman who washed ashore with amnesia in Florida. However, the premise of Overboard also bears some similarities with Lina Wertmüller’s 1974 film Swept Away (Travolti da un insolito destino nell’azzurro mare d’agosto), in which a wealthy woman (Mariangela Melato) and a crewmember (Giancarlo Giannini) of the yacht on which she is traveling become stranded on a desert island. A number of Dixon’s most high-profile subsequent projects – such as The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), Freaky Friday (2003), and Hairspray (2007) – have been reworkings/reimaginings of other movies. (Swept Away was remade more directly in 2002 by Guy Ritchie.)

Dixon’s script is sharp and witty, though the direction by Garry Marshall is flat and insipid. (Is it controversial to suggest that the films for which Marshall is chiefly remembered as a director – Pretty Woman, Frankie and Johnny, Beaches – coast by on the quality of their scripts?) The film was the subject of an insipid Hollywood remake in 2018, which unnecessarily tried to add a ‘spin’ to the material by reversing the gender roles, but failed to replicate the chemistry of the pairing of Hawn and Russell.

Video

Overboard is presented on Severin Films’ region ‘A’-coded Blu-ray release in its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1. Filling slightly under 34Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

Shot on 35mm colour stock, this presentation of Overboard is based on a new 2k scan (of the interpositive, it seems). The colour palette is deep and naturalistic, and there’s a pleasing level of detail throughout the presentation. (A gauze is noticeably used over the lens for some of the on-water shots: the evident presence of this is testament to the level of detail in this HD presentation.) The film’s photography is fairly uninspiring but nevertheless allows the performances to take centre-stage. Contrast is very good, with a pleasing curve into the toe of the exposure and balanced highlights. An organic, film-like grain structure is present, though the coarse nature of this underscores the (reputed) IP source – rather than the finer grain structure that would have been facilitated by a scan of the negative.

All in all, this is a very pleasing, film-like presentation of Overboard.

Audio

In terms of audio options, Severin Films’ presentation of Overboard provides the viewer with the option of watching the film in English (natch), French, or Spanish. All audio tracks are DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0. The English track is fine, with some pleasing bass. Range is more than acceptable, though this is a dialogue-heavy track and certainly not ‘showy’. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided: these are easy to read, and accurately transcribe the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes, as its key contextual feature, ‘Writing Overboard – Interview with Screenwriter Leslie Dixon’ (14:19 mins): a sit-down with the film’s writer.

Dixon talks about how she came to be a writer, moving to Los Angeles after an epiphany that occurred whilst she was working as a singer with a band in San Francisco – something she realised wouldn’t provide a future for her. Once in LA, she taught herself how to write screenplays by reading scripts that she borrowed from the AFI.

Dixon was partly inspired by the screwball comedies of the 1930s, and by Preston Sturges’ work in particular. Overboard was her second professional writing job, and she bonded with studio executive Alan Ladd, Jr, over a shared love of golden age Hollywood films.

She says that she struggled to write Overboard, because she realised that she was trying to ‘make something up out of arguably a creaky premise [amnesia]’. When the script was completed, it was sent to Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell rather than the director – and the actors loved it, as it presented them with an opportunity to work together.

Dixon also talks at length about her original intentions for the film’s ending, which differ quite substantially from what we see in the final film. She suggests that the film’s success largely hinges on the ‘chemistry’ between Russell and Hawn.

Also included is the film’s trailer (1:55 mins).

Overall

Overboard is a film whose interest, to a greater extent, rests on the chemistry of its two lead actors: Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell had fallen in love with one another after appearing together in Jonathan Demme’s Swing Shift (1984). (Since then, they have co-starred in a number of films.) Hawn and Russell’s charisma and interplay helps to blindside the viewer, preventing them from seeing how Joanna and Dean’s relationship, when divorced from the broad humour, is deeply… well, the word ‘abusive’ wouldn’t be too much of a stretch. Importantly, Dean’s ‘gaslighting’ of Joanna is not just about sexual politics (something which is all too easy to acknowledge in the post-#MeToo era) but also, fundamentally, an example of class-based revenge. Both parties evolve and become domesticated as a response to their experiences with one another: Joanna is knocked from her high society perch and learns to be maternal and nurturing, and Dean is encouraged to become more responsible whilst also allowing some of Joanna’s confidence to rub off on him (leading him to develop the crazy golf course). On a personal level, I find it difficult to detach this film from the love that my grandmother (who passed away in the 1990s) had for it, and I vividly remember watching it with her when I would visit my grandparents at weekends. Overboard is an entertaining film, with a certain je ne sais quoi, given by the leads and Dixon’s script, that the cynical 2018 remake failed miserably at emulating.

Severin Films’ Blu-ray release of Overboard contains a very good, film-like presentation that is supported by an excellent interview with the film’s writer, Leslie Dixon. (A feature-length documentary about Dixon – who has worked as writer and producer on a series of Hollywood films – would be more than welcome, in all honesty.)

Overboard (1987) is available from Severin Films now. For more information, please click here.