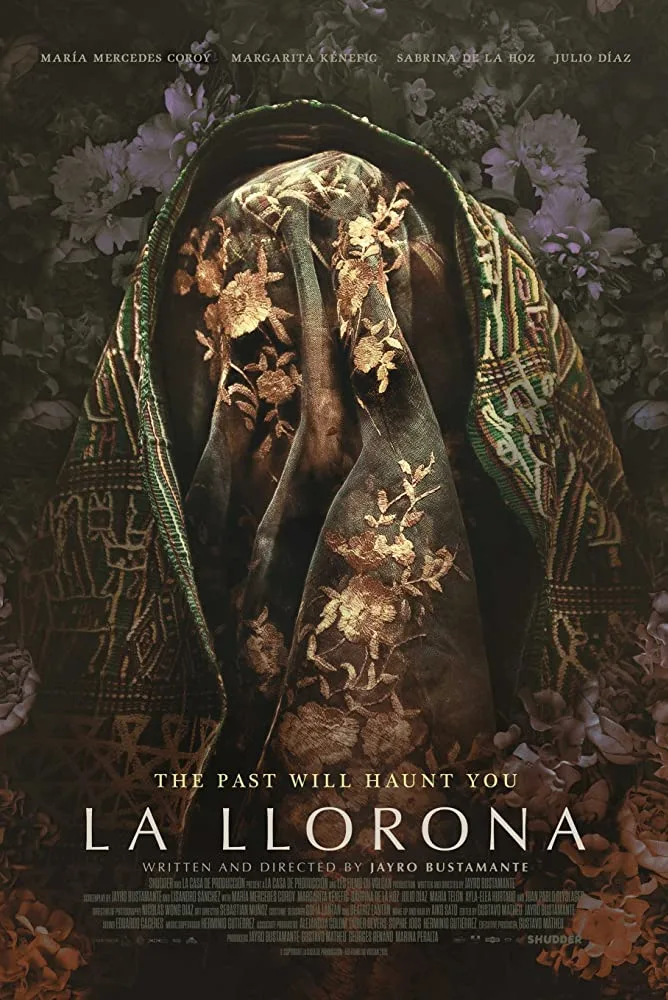

In case you, like me, have some holes in your world history and were hoping that Don Enrique Monteverde (Julio Diaz) was invented for this film- I’ve got some bad news. Monteverde is a dead ringer for Guatemalan leader and General José Efraín Rios Montt, who is very real indeed. Montt led the military government from March 1982 to August 1983, and in 2013 was convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity for his role in the Guatemalan genocide- destroying villages and killing, disappearing, or displacing indigenous Mayan peoples. The horror in Jayro Bustamante’s La Llorona, is very real, and is first and foremost human horror.

The film begins with the Don and his cabinet subdued— his trial is not going well. While his ministers fret and his wife prays, Enrique sips his whiskey and coldly remarks to one despondent minister, “Age has turned you into a coward.” Life at home belies his public coolness. Enrique wakes to the sounds of a woman crying, grabs a gun, and staggers through his labyrinthine mansion searching for the source of the disruption. It would seem that age has made Monteverde delirious; dementia is beginning to take hold of the ailing fallen dictator. The staff, mostly indigenous folk, scared of Enrique, scared of the angry mobs outside his home, quit. Valeriana, his one loyal servant, stays on. She even tries to bring in new help from her village. Only Alma, played with an ethereal quiet by María Mercedes Coroy, answers the call, arriving with little more than a white dress and a deep sadness.

While her arrival coincides with the General’s conviction being overturned (this is true of the real-life Montt, as well), the situation does not improve in the Monteverde house. Protestors remain outside, and the family – Enrique, his wife Carmen, his daughter Natalia, and his granddaughter Sara, along with their reduced staff – are effectively prisoners in their own home. Nerves continue to fray, the general’s health and mental state remain precarious, and something seems off about the new girl. Could she be the eponymous ghost?

As the story of La Llorona is rooted in oral tradition, the specifics vary, but she is a Latin American iteration of the Lady in White legend. Typically, her story reads something like this: In life, La Llorona was known as Maria, a beautiful mother of two. She is jilted by her lover, and in a fit of pain and rage, drowns her children in a river. Emerging from this fevered moment of insanity, she realizes the gravity of what she has done, and overcome with remorse, kills herself. Unfortunately, her crimes bar her from entering Heaven, and she is instead doomed to roam the countryside, weeping as she searches for her children. In fact, her name translates to “The Wailing Woman”, or sometimes just “the Crier”. In her spectral madness, she is not particularly discerning in her search and will snatch any wandering child she can and drown them. Parents invoke this boogeyman to discourage their children from staying out late. Bustamante, however, is preoccupied with an evil that is far greater, and more human.

At first blush, Alma appears to be the embodiment of La Llorona, wearing a white frock and waist-length dark hair. She has an unhealthy fascination with water, playing a game where she encourages Sara to try to hold her breath for as long as possible. She even confides in the young girl that her two children are dead. But Bustamante keeps you guessing. While scenes will momentarily infuse Alma with menace, they’ll pull back, revealing the otherworldly as mundane. Remember, she is not the real monster here; Don Enrique is. In a particularly haunting scene, his monstrousness is laid bare as Mayan-Ixil victims testify to his atrocities. The general who terrorized the countryside is the true boogeyman.

Recognizing these depths of human cruelty as the real horror, Bustamante reimagines the legend of La Llorona. He redistributes the story beats of the titular phantom among his leading characters: Alma has lost her children, Enrique has innocent blood on his hands, and Carmen (Margarita Kenéfic), wrestles with the guilt over her husband’s actions and her implicit support in standing by him. It’s actually Carmen’s character arc that drives this story and binds the elements together. Alma is largely a catalyst, and Enrique, in his rational moments, shows no compunction for what he has done. Carmen’s internal struggle, on the other hand, highlights the guilt that we associate with La Llorona, and it is her reckoning that guides the narrative. Kenéfic’s depiction of a woman grappling with the ramifications of her choices grounds the film and strengthens its theme of moral obligation.

Interestingly, this may not be La Llorona’s first brush with genocide. Some identify her origins with the story of La Malinche, an indigenous Nahua woman taken as an interpreter and mistress by Hernán Cortés. Her role as an advisor to his conquistadors was integral in their conquest of the Aztec empire. In this conception, La Llorona’s crime against her children derives from La Malinche’s betrayal of her people. Carmen’s predicament and tacit approval of her husband’s tactics echoes the role of La Malinche, and further develops the question of culpability.

Having grown up in a Chicano neighborhood in Southern California, I spent my childhood sprinting home at nightfall to avoid the clutching grasp of La Llorona. I know the legend all too well, and, perhaps to its detriment, the film assumes that familiarity. Bustamante and co-writer Lisandro Sanchez have certainly crafted a powerful psychological thriller, but in repurposing the folklore, they ultimately have to rely more heavily on the viewer’s knowledge and fear of the Weeping Woman. As with many movies that seek to blend human horror with the supernatural, it is a balancing act, and scare-oriented genre fans may be disappointed by a decided lack of supernatural horror throughout much of the film. Struggles with balance rear up briefly in pacing as well. For a film that carefully charts the collapse of a family and excels in building paranoia through deliberate pacing, the conclusion feels a little rushed. La Llorona delivers a strong ending, but in stark contrast to the very intentional flow of the film, it feels a bit frenetic as it tries to tie everything up.

Still, the result is a tense exploration of guilt and sanity. Can we escape the ghosts of our past? Can a debt this unimaginable be repaid? And who should pay? By steeping the film in the Llorona myth but focusing on the moral burden and deterioration of the Monteverde family, Bustamante ensures that the horror in La Llorona derives from the sins of the father, spinning a campfire tale for children into a fantastic, slow-burning, drama with a supernatural bent.