If you’ve seen your share of historical martial arts movies, chances are you’ve heard the name Wong Fei-Hung. A real life pioneer of Kung Fu and Chinese medicine and all-around folk hero, he’s been heavily mythologised in Hong Kong action cinema, notable films including Drunken Master and Iron Monkey. However, where both those films followed a young Wong before he became the figure of legend, the Once Upon A Time In China series showcased him at the height of his powers. Beyond this, the series – or its earlier entries, at least – made a point of exploring the troubled state of the nation during Wong’s lifetime, in the last years before the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912. Of course, given the films were made in Hong Kong in the early 1990s – i.e. immediately prior to the region returning to Chinese rule – it’s hard not to ponder the historical parallels. In all this, Once Upon A Time In China became arguably the last great franchise to emerge from that golden era of Hong Kong action film-making, and many would say they’ve remained the crowning achievement of both leading man Jet Li and director Tsui Hark. This being the case, it’s very nice to see the series (or, at least, the bulk of it) come to Blu-ray in the UK via Eureka Entertainment, who’ve been doing a great job bringing Hong Kong action classics to HD of late.

If you’ve seen your share of historical martial arts movies, chances are you’ve heard the name Wong Fei-Hung. A real life pioneer of Kung Fu and Chinese medicine and all-around folk hero, he’s been heavily mythologised in Hong Kong action cinema, notable films including Drunken Master and Iron Monkey. However, where both those films followed a young Wong before he became the figure of legend, the Once Upon A Time In China series showcased him at the height of his powers. Beyond this, the series – or its earlier entries, at least – made a point of exploring the troubled state of the nation during Wong’s lifetime, in the last years before the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912. Of course, given the films were made in Hong Kong in the early 1990s – i.e. immediately prior to the region returning to Chinese rule – it’s hard not to ponder the historical parallels. In all this, Once Upon A Time In China became arguably the last great franchise to emerge from that golden era of Hong Kong action film-making, and many would say they’ve remained the crowning achievement of both leading man Jet Li and director Tsui Hark. This being the case, it’s very nice to see the series (or, at least, the bulk of it) come to Blu-ray in the UK via Eureka Entertainment, who’ve been doing a great job bringing Hong Kong action classics to HD of late.

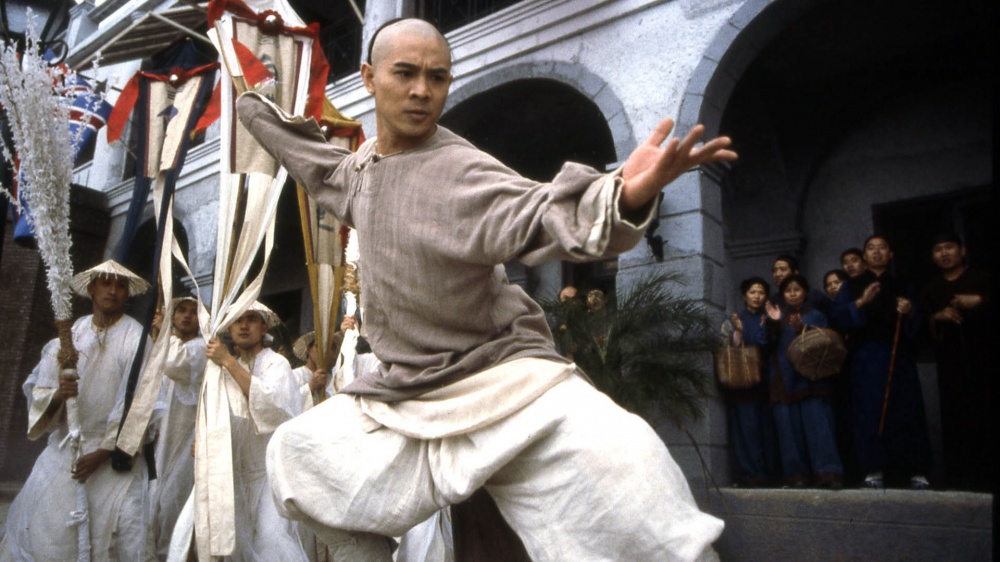

1991’s original Once Upon A Time In China (simply entitled Wong Fei-Hung on its native shores) is, to be frank, a fairly rare breed of martial arts film: one in which the plot and its broader context are every bit as compelling as the acrobatic action. Even the staunchest defender of the genre has to admit that much of the time the story in these movies is there primarily to string the fight scenes together, but in this case we’re presented with a genuinely fascinating story world in which the conflicts that are not necessarily resolved physically still pack as great a punch. Li’s Wong is a martial arts instructor and physician in Foshan, where tensions abide thanks not only to local criminal gangs, but uneasy relations with Western settlers. Wong’s own feelings on this matter are challenged with the arrival of Siu-Kwan (Rosamund Kwan), whom he insists on addressing as 13th Aunt (they’re distantly related by marriage) for matters of propriety, despite the fact that they’re roughly the same age and clearly attracted to one another. Siu-Kwan has spent much time in the West and has come home wearing their clothes, speaking their languages and utilising their technology, none of which sits well with the staunchly traditional Wong, who is one among many suspicious of the West and its impact on China’s culture and identity. They’re given ample reason to doubt the West further once it comes to light that American officials are quietly dealing in human trafficking, which naturally isn’t something the bold martial artist will take lying down.

On top of boasting really quite beautiful production design and cinematography, Once Upon A Time In China also had a hand to play in establishing the more lavish, wire-based martial arts choreography which swept Hong Kong in the 1990s, and not long thereafter made its presence felt in Hollywood. It does seem curious that the filmmakers would choose to utilise such flagrantly non-naturalistic, gravity defying fighting techniques for a film ostensibly based on real characters and events (although truthfully I’ve no idea how historically accurate any of it is: I suspect the answer is ‘not very’). That’s just Kung Fu movies for you; without the sense of spectacle, the rest of it just isn’t there, and if you can’t suspend your disbelief accordingly you’re robbing yourself of some real enjoyment. Sure, the HD presentation means the wires are occasionally even more visible than they were beforehand, but there’s no denying there’s some thrilling action in here, and this remains the one defining trait that runs through all the films in this box set.

This is not to say that the Once Upon A Time In China series immediately fell prey to the law of diminishing returns, however, as 1992’s Once Upon A Time In China II improves on its already impressive forebear in just about every respect. Not only that, but it advances the core theme of China’s turn-of-the-century identity in an intriguing and perhaps unexpected manner. As previously stated, these films arrived in the run-up to Hong Kong being re-appropriated by China in 1997 (technically they’re all HK-Chinese co-productions), and as such it doesn’t seem too great a stretch to deem them propaganda for spreading Chinese nationalism, particularly given how heavily the first film would seem to demonise the Western influence. By contrast, the core threat in the sequel is a fanatical sect of Chinese nationalists preaching religious fundamentalism and extreme xenophobia, declaring that anyone and anything they deem tainted by foreign influences must be destroyed. In challenging this, Wong – and the film itself – clearly lean in a moderate direction, recognising that cultures need to embrace change, and that this needn’t equate to the destruction of all they hold dear; no small point, given that those most resistant to change frequently cause the most destruction. And of course, as much as this film builds on its predecessor in theme and narrative, it also ups the ante on the action; and it obviously doesn’t hurt that Donnie Yen joins the cast as a shady police official, who – but of course – trades blows with Li’s Wong.

These first two films set the bar pretty damn high, so it was sadly inevitable things could only go down from there. Even so, while 1993’s Once Upon A Time In China III is clearly a lesser film, it’s still a fine piece of entertainment. Political overtones are somewhat less prominent this time around, with a greater emphasis on building on the characters in a more light-hearted, almost sitcom-like fashion, in particular the awkward romance between Wong and 13th Aunt, as she’s still most commonly known. The main plot thread of a competition between lion dance troupes feels somewhat slight in comparison to the first two films, but it still leads to plenty of wire-enhanced fun and frolics, and there’s still a bit of political intrigue thanks to some meddling in local affairs by shady Russian politicians. Ooh, contemporary resonance.

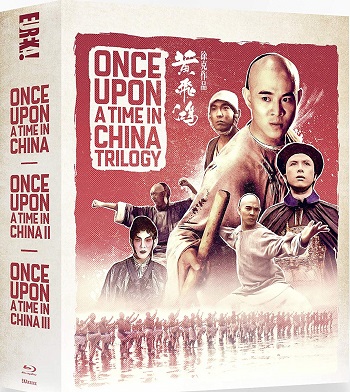

One might be forgiven for wondering just why Eureka are selling this new box set as the Once Upon A Time in China trilogy, given that it actually boasts four films. Well, it seems this is one of those instances where many prefer to think of the series of having ended at that point. Not included here are the fourth and fifth entries in the series, made in 1993 and 1994, without Jet Li, Tsui Hark or any of the key players from the original trilogy; while I haven’t seen either film I gather they’re not held in anywhere near as high a regard. Nor is the fourth and final film in the box set, 1997’s series closer Once Upon A Time In China and America, which follows Li’s Wong, Kwan’s Siu-Kwan and returning Part 3 actor Hung Yan-yan as Wong’s student Clubfoot Seven, as they venture into the Wild West for the opening of the first Chinese medicine clinic in America. While it deals heavily with the oppression and bigotry faced by the first Chinese-Americans, all in all this a far goofier proposition than the preceding films, awkwardly blending Kung Fu action and broad Hong Kong humour with the motifs of the Western, to often somewhat cringe-worthy effect. Tsui Hark’s replacement behind the camera by another HK legend, Sammo Hung, may have had a detrimental effect there; while Sammo may be a true master, he’s certainly not known for his subtlety. No one’s helped by the meandering and overloaded narrative, sidetracked by a rather tedious thread in which Wong suffers amnesia and is taken in by a Native American tribe. On which note, the prevalence of both Western and Asian actors donning redface isn’t likely to go over well with much of the contemporary audience.

All this having been said, Once Upon A Time In China and America is still undemanding fun, and certainly shouldn’t detract from the overall desirability of this box set. While regrettably I haven’t had time to have a proper look at the extras, there’s plenty of them, with new and archival interviews with key cast and crew members, commentary tracks, behind the scenes material, a 48 minute featurette on the real Wong Fei-Hung, and a collector’s booklet boasting essays on all the films from James Oliver. While the latter two films may be largely disposable, the first two might well be among the very best Kung Fu films ever made, so no fan of the genre should overlook this set.

Eureka Home Entertainment’s Once Upon A Time In China Blu-ray box set is available now.