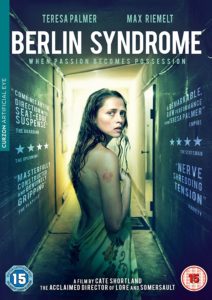

It seems that films in which women are sequestered in the name of romance yet wind up trapped and fighting for their lives are like buses; you wait for ages, then two show up at once. Okay, technically Berlin Syndrome arrived a fair bit sooner than Gerald’s Game, as it was released to limited cinemas earlier this year following a number of festival screenings including Sundance, Glasgow and (appropriately enough) Berlin. Still, as it hits home entertainment now, it’s hard not to notice the thematic and narrative similarities between Mike Flanagan’s Stephen King adaptation, and Cate Shortland’s take on Melanie Joosten’s novel. Not that this is something to get too hung up on, however, as Berlin Syndrome quickly proves to be a very different, almost equally compelling work, with a haunting power all of its own.

Our central protagonist is an Australian backpacker named Clare (Teresa Palmer, who’s been in so many US productions – Warm Bodies, Lights Out, Hacksaw Ridge – that I don’t think I’ve ever seen her play an Australian role before now). Visting Berlin solo, Clare’s ostensibly there to take photos of the city for an art book she’s working on, but really she’s there in the hopes of some life-changing experience. Exploring the city, she crosses paths with Andi (Max Reimelt of Sense8 and We Are The Night), a handsome, charismatic teacher whom just about any straight woman would surely be delighted to take home to mother. The two hit it off, he shows her some sights of the city – the real city, in what had been East German territory before the Berlin Wall came down – and, naturally, he soon takes her back to his place, which would appear to be the only habitable apartment in a remote, run-down complex. A night of passion ensues, and everything seems to be going just right… until, after he leaves for work in the morning, Claire finds herself locked in without a key. She takes this for a simple mistake on his part at first, and when he returns that evening he insists it was just that – but then the same thing happens the next day, bringing Claire to the alarming realisation that her seemingly perfect guy has made her his prisoner.

It’s easy to assume going in, as I did, that Berlin Syndrome is setting itself up as another breakneck survivalist thriller in which a terrified but resourceful woman fights off a psychotic predatory male, along the lines of Red Eye or P2. However, while there are certainly aspects of that here, Berlin Syndrome has something rather different in mind. First off, after a spot of Googling I think I can safely assume the title does not in any way refer to the actual condition of Berlin syndrome (apparently some kind of ectodermal dysplasia), but rather plays on Stockholm syndrome, which as I expect more readers are aware hinges on an emotional bond between the hostage and the captor. The film plays out in a far more realistic and grounded fashion than many similarly themed thrillers, and when Claire’s first escape attempts reveal that she doesn’t in fact have any of those hidden reserves of superhuman strength which Final Girls so often summon forth, she comes to accept her situation. What makes the whole set-up all the more disturbing is that, while a few subtle red flags are thrown up along the way, we don’t know for sure that Andi’s a bad guy until the moment he locks her in, and up to that point it really does seem a romantic bond is growing between them. Then, once Claire’s fight leaves her, a seemingly genuine sense of love between the two resurfaces. We’re not sure to what extent Claire is playing along simply to lull him into a false sense of security, or if she genuinely wants to please him. Either way, it’s a real descent into madness arc which Palmer handles beautifully, and making it all the more effective is the fact that Reimelt never plays Andi as a villain, as easy as it would have been to do so. Deplorable though his actions are, he remains human and, in his own way, easy to empathise with, all of which makes the whole thing all the more disturbing.

It’s easy to assume going in, as I did, that Berlin Syndrome is setting itself up as another breakneck survivalist thriller in which a terrified but resourceful woman fights off a psychotic predatory male, along the lines of Red Eye or P2. However, while there are certainly aspects of that here, Berlin Syndrome has something rather different in mind. First off, after a spot of Googling I think I can safely assume the title does not in any way refer to the actual condition of Berlin syndrome (apparently some kind of ectodermal dysplasia), but rather plays on Stockholm syndrome, which as I expect more readers are aware hinges on an emotional bond between the hostage and the captor. The film plays out in a far more realistic and grounded fashion than many similarly themed thrillers, and when Claire’s first escape attempts reveal that she doesn’t in fact have any of those hidden reserves of superhuman strength which Final Girls so often summon forth, she comes to accept her situation. What makes the whole set-up all the more disturbing is that, while a few subtle red flags are thrown up along the way, we don’t know for sure that Andi’s a bad guy until the moment he locks her in, and up to that point it really does seem a romantic bond is growing between them. Then, once Claire’s fight leaves her, a seemingly genuine sense of love between the two resurfaces. We’re not sure to what extent Claire is playing along simply to lull him into a false sense of security, or if she genuinely wants to please him. Either way, it’s a real descent into madness arc which Palmer handles beautifully, and making it all the more effective is the fact that Reimelt never plays Andi as a villain, as easy as it would have been to do so. Deplorable though his actions are, he remains human and, in his own way, easy to empathise with, all of which makes the whole thing all the more disturbing.

Still, while Berlin Syndrome is a handsome-looking film driven by two compelling lead performances, it does lose momentum a little in the scenes that take us away from that central relationship. A subplot involving one of Andi’s pupils never quite convinces, which is a bit of a problem as this thread comes into play in the final scenes. There also undertones of political unrest rooted in the history of the previously divided city which are intriguing, yet feel perhaps a little underdeveloped; I’ll admit, this may reflect my own relative ignorance of the history of Germany since the fall of the wall, and if the film encourages viewers like myself to learn more about that, surely that can only be a good thing. Either way, Berlin Syndrome is an impressive piece of work that’s well worth watching.

Berlin Syndrome is available on DVD, Blu-ray and video on demand now, from Curzon Artificial Eye.