To the best of my recollection, the first time I heard the name Lee Marvin was in Reservoir Dogs, when Mr Blonde suggested Mr White must be a fan of his. Personally, I’m afraid to say I never really have been. Not that I have anything against the actor, I’ve just never seen enough of his work to really form an opinion; never been a big viewer of old war movies or westerns, never watched The Dirty Dozen or The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. If you choose to stop reading now in disgust at my ignorance, I’ll understand.

All this being the case, Point Blank has always been a film I’ve been aware of primarily by association with other films. While I might not be too well versed in Lee Marvin, I have long admired the work of director John Boorman, primarily his 70s/80s works: Deliverance, Zardoz, Excalibur, The Emerald Forest (truth be told, I don’t even mind The Exorcist II). I’m also aware that Point Blank was remade – or, at least, another movie adaptation of Donald Westlake’s novel The Hunter was produced – as the 1999 Mel Gibson movie Payback, and that Westlake’s character, featured in a series of novels, was also the basis of the more recent Jason Statham movie Parker. As both of these were fun but fairly straightfoward hard-boiled thrillers, I didn’t necessarily anticipate much different from Boorman’s movie, the English director’s first work in Hollywood (astonishingly, his only feature credit up to that point was the Dave Clarke Five movie Catch Us If You Can).

However, Point Blank hit screens in 1967. This, as is noted in the commentary track – a discussion between Boorman and fellow director Steven Soderbergh, who cites the film as a major influence on his own work, most pointedly on his 1999 crime thriller The Limey – was the beginning of that brief but vital period in which the director was king in Hollywood, breaking with convention was the order of the day, and the barriers on what was allowed to be shown on screen began to fall. While Point Blank isn’t necessarily quite such a groundbreaker in terms of sex and violence as other films of the era, even 50 years later it remains quite the eye-opener, given that what on paper reads as a simple tale of robbery and revenge is cut together in so abstract and disorienting a manner, it leaves the viewer questioning more or less everything they’re shown. How much of this is real? Is anything real? If it is real, is all of it or some of it just a memory? What’s actually happening right now? These are just some of the questions liable to cross your mind throughout. It’s interesting that Boorman also notes that the initial script for the film was so hated both by Marvin and himself that they binned it and started from scratch – yet, the director says, Mel Gibson’s Payback plays out as if it was using that very same script they threw out.

However, Point Blank hit screens in 1967. This, as is noted in the commentary track – a discussion between Boorman and fellow director Steven Soderbergh, who cites the film as a major influence on his own work, most pointedly on his 1999 crime thriller The Limey – was the beginning of that brief but vital period in which the director was king in Hollywood, breaking with convention was the order of the day, and the barriers on what was allowed to be shown on screen began to fall. While Point Blank isn’t necessarily quite such a groundbreaker in terms of sex and violence as other films of the era, even 50 years later it remains quite the eye-opener, given that what on paper reads as a simple tale of robbery and revenge is cut together in so abstract and disorienting a manner, it leaves the viewer questioning more or less everything they’re shown. How much of this is real? Is anything real? If it is real, is all of it or some of it just a memory? What’s actually happening right now? These are just some of the questions liable to cross your mind throughout. It’s interesting that Boorman also notes that the initial script for the film was so hated both by Marvin and himself that they binned it and started from scratch – yet, the director says, Mel Gibson’s Payback plays out as if it was using that very same script they threw out.

The premise is indeed simplicity itself. Marvin is Walker (Parker in the novel and the Statham movie, Porter in Payback – your guess is as good as mine), and in the film’s opening seconds we see him shot by Mal Reese (John Vernon, later seen in such exploitation classics as Red Heat and Savage Streets). As a barrage of moments are thrown at us in nothing resembling linear order, it becomes clear that Walker and Mal are old friends, and Walker has agreed to partner with Mal on a robbery. However, once the crime proves a success and the men rendezvous with Walker’s wife Lynn (Sharon Acker) at the now-abandoned Alcatraz, Mal turns on his friend, gunning him down and making off with both his wife and his cut. Yet it would seem Walker makes not only a miraculous recovery, but also manages to get off Alcatraz island just fine, and – with the assistance of an enigmatic benefactor, Yost (Keenan Wynne) – he sets about taking his revenge, and naturally this goes higher than his treacherous friend and spouse.

Yet as much as Point Blank might seem a standard gun-toting revenge flick, Boorman – a director who would come to specialise in adding a mythic dimension to his work, up until he embraced myth whole-heartedly on Excalibur – adds a subtly other-worldly feel to proceedings which is baffling, yet fascinating. This feeling is not solely down to the non-linear editing but also in the art direction, with entire scenes colour-coded (clothing and scenery in matching shades of red, yellow, blue, grey etc.). From a modern perspective, it might be easy to dismiss such flourishes as meaningless self-indulgence designed to tart up an unremarkable narrative, yet it all seems to work through the power of the direction and the performances. Central to this, of course, is Marvin’s steely turn as Walker, who in the midst of so much weirdness remains the quintessential man’s man, in the classic, emotionless, taciturn spirit of the day. It’s a performance which would certainly seem to point toward such future anti-heroes as Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle, Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan and Charles Bronson’s Paul Kersey, defining what it meant to be a real big screen tough guy in the days before Stallone and Schwarzenegger drowned it all out in string vests and baby oil. Plus, exploitation aficionados will be delighted by the presence of Angie Dickinson, another cult icon whose work I must confess to not knowing as well as I probably should.

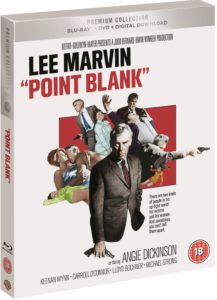

A distinctive and compelling piece of work, Point Blank stands proud as the starting point of John Boorman’s Hollywood career, reasserting my admiration for the director – and I daresay it may make a Lee Marvin fan of me yet. Existing fans, of course, should need little persuasion to snap up this dual format Blu-ray/DVD, available now exclusive to HMV as part of Warner Bros’ premium collection, with extras including the aforementioned Boorman/Soderbergh commentary, theatrical trailer, and two-part vintage featurette ‘The Rock,’ focused on the film’s use of Alcatraz.