Some mild spoilers within.

Some mild spoilers within.

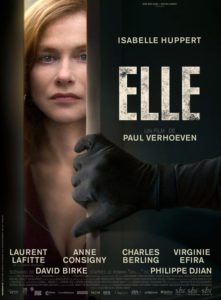

I had an interesting discussion about Paul Verhoeven’s Elle with a fellow member of the cinema audience recently, and the most striking thing to me that she said – more striking than her conclusion that film was definitely misogynist – was that when she chose to come to see it she knew that Isabelle Huppert wouldn’t be in anything that sick. Now, my favourite Isabelle Huppert role is in The Piano Teacher, so I must say I was expecting the exact opposite, I suspect, of my fellow movie-goer, and I was not disappointed in that regard. It seemed my fellow audience member had taken the film at its most superficial, and I suspect she’s never seen The Piano Teacher, either. There was a great deal of nuance and restraint to the sickness in Elle, and it is that which elevates it to a film which is hugely enjoyable – and yes, very funny – without incurring the wrath I usually have reserved for lazier attempts at rape-revenge films.

Elle has been frequently described as a ‘rape-revenge comedy’ (a label Verhoeven himself objects to); I think to do so is reductive of the film on offer. The label ‘comedy’ has been attached to several films that don’t seem to deserve it, lately – Toni Erdmann, Get Out – but that’s not to say these films aren’t funny. To me, the word ‘comedy’ evokes a certain expectation that none of these films meet, despite making me laugh. I don’t want to be one of those genre bores that thinks they’re somehow ‘elevated comedy’ – god, no – but I do think there is a difference between a ‘rape-revenge comedy’ and, to paraphrase Verhoeven, a film which features rape, revenge and comedy.

The centre of the film is the character of Michèle Leblanc (Huppert), the owner of a small but successful video game company who is brutally attacked in her own home by a masked assailant. Her response to being raped is not as we might expect: she sweeps up, orders dinner, and seems to move on. Despite life continuing on she begins something of a cat-and-mouse game with her attacker, seeking out his identity all while continuing to navigate her job and her complicated personal life: a useless son (Jonas Bloquet), an ex-husband (Charles Berling), an eccentric mother (Judith Magre) and a myriad of friends and lovers. Despite a broad canvas of characters there is no doubt at all the Huppert and Michèle are the stars of this show.

The centre of the film is the character of Michèle Leblanc (Huppert), the owner of a small but successful video game company who is brutally attacked in her own home by a masked assailant. Her response to being raped is not as we might expect: she sweeps up, orders dinner, and seems to move on. Despite life continuing on she begins something of a cat-and-mouse game with her attacker, seeking out his identity all while continuing to navigate her job and her complicated personal life: a useless son (Jonas Bloquet), an ex-husband (Charles Berling), an eccentric mother (Judith Magre) and a myriad of friends and lovers. Despite a broad canvas of characters there is no doubt at all the Huppert and Michèle are the stars of this show.

Michèle has been described as unlikeable and while I certainly wouldn’t want to be friends with her in reality, in the context of the film I found her oddly endearing – a moment in which she shows utter disregard for her ex-husband’s car completely won me over, despite it being totally mean-spirited. She’s a rich and complex character, and to think of her as somehow standing in for all womankind in her responses to her attack is ridiculous, given that she is established as unconventional from the get-go – she’s a well-to-do middle-class, middle-aged woman running a video game company, as well as, it emerges, the daughter of a serial killer who has been considered complicit with her father’s crimes since childhood. Michèle is quite evidently not meant as some sort of broad-strokes ‘everywoman’ character, and to therefore take the rest of the film as somehow representative of all women is hugely disingenuous. Yes, Michèle’s response to her attacker is problematic, but it is presented as thus – the film doesn’t invite us to interpret her response as in any way normal. Depicting abhorrent acts as well as abhorrent responses in a film do not make that film itself abhorrent.

The sense of dread in the film is subtle but ever-present, even in scenes which are funny or in which Michèle appears to be in control of her situation. It’s evident that she plays dangerous games in her life, and that extends to the period in which see her, after her attack. There was a wonderful sense, after the film, of relief that her cat seemed to escape the film unscathed (something I’d wondered about before watching it) – only I soon realised that, actually, the cat seems to just disappear in the second half of the film. That detail was a wonderful confirmation that is a film that constantly undermines any feelings of safety or reassurance that might creep in while watching, and that that was precise and meaningful.

What was most fascinating in the film, for me, was the mirroring and reflecting of Michèle in other characters in the film, particularly in her best friend Anna (Anne Cosigny), as encapsulated, for me, in the film’s ending. As such there’s much more to the film’s exploration of Michèle as a character than just her rape, and in that sense it’s a most remarkable film. Anyone expecting arch-exploitation will be disappointed in the film, perhaps, but then those expecting a nice arthouse drama might likewise find it overly exploitative. For me, it was actually a wonderful balance of both, and that certainly contributed to my enjoyment of it. Elle certainly is not a film for everyone, but with an open-mind and a taste for dark humour, it’s a richly rewarding experience.